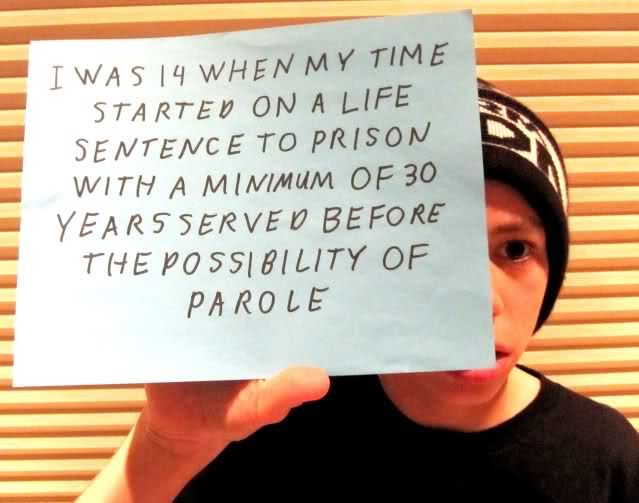

I’ve been teaching and taking college students into both “adult” state prisons and juvenile correctional facilities for a number of years now. One thing that always stands out is how very young many of the men in prison were when they committed their crimes. In a visit with the penitentiary’s Lifers Club, I could look around the room and see former students of mine who were 14, 15, and 16 at the times of their crimes and have been or will be locked up for most of their lives. The photo above is from the tumblr site, “We are the 1 in 100” that my students and I created to represent perspectives from those inside of prison and those affected by the prison sentences of their family members, friends, and classmates. The sentiment was written by one of my inside students, based on his own experience (although the card is held by a young man on the outside). He was convicted as an adult at age 14 and sentenced to a minimum of 30 years. He’s about 10 years into his sentence now, and he is a remarkable young man – smart, motivated, driven to do something meaningful with his life. I’ll be working with him again this fall, and I’m looking forward to what he can teach me and my other students.

I’ve been teaching and taking college students into both “adult” state prisons and juvenile correctional facilities for a number of years now. One thing that always stands out is how very young many of the men in prison were when they committed their crimes. In a visit with the penitentiary’s Lifers Club, I could look around the room and see former students of mine who were 14, 15, and 16 at the times of their crimes and have been or will be locked up for most of their lives. The photo above is from the tumblr site, “We are the 1 in 100” that my students and I created to represent perspectives from those inside of prison and those affected by the prison sentences of their family members, friends, and classmates. The sentiment was written by one of my inside students, based on his own experience (although the card is held by a young man on the outside). He was convicted as an adult at age 14 and sentenced to a minimum of 30 years. He’s about 10 years into his sentence now, and he is a remarkable young man – smart, motivated, driven to do something meaningful with his life. I’ll be working with him again this fall, and I’m looking forward to what he can teach me and my other students.

At the same time, for the past 6 years, I have taught Oregon State University’s incoming freshmen football players in a summer bridge program designed to help them make a smooth transition to college and the accompanying responsibilities. Every summer I have arranged to take them to one or more of our state prisons and juvenile correctional facilities to talk with inmates, see the institutions, and to get outside of the classroom to learn about social problems. It is easily the most impactful experience of the class.

It’s generally the case that at least a few of my student-athletes in the summer have not yet turned 18. I make an effort to talk to their parents and to ensure that I get waivers signed before our field trips; parents seem to trust that if a woman like me can spend that much time in prison, their young and often very large sons will probably be okay.

So here’s the irony…the maximum-security prison will not allow my 17-year-old students to visit/tour the facility and meet the inmates. I’m not entirely sure of the reasoning – the waiver releases the Department of Corrections of responsibility should any incidents arise (although they never have) and parents sign on behalf of their minor sons. Perhaps, the prison administration does not want minors to be exposed to inmates and the harsh realities of prison life. Yet, the young man convicted at 14 has lived in that very prison for a number of years. How can we possibly treat 17-year-old college students as incapable of making a decision about a 1-day experience, yet judge young teenagers as fully responsible for their criminal behavior.

The debate about life sentences for juvenile offenders is both important and timely. Perhaps with a fresh look, we can critically evaluate the accumulated evidence (including the emerging data on brain development and maturity) and create new, thoughtful, considered sentencing structures and policies for juvenile offenders who have committed serious crimes.