Frederick Melo at The Usual Suspects comments on the high rates of advanced degrees among police officers in Minnesota. He cites a bit of the criminological research literature on the effects of higher education, but didn’t mention a new paper in Police Quarterly by Jason Rydberg and William Terrill.

Frederick Melo at The Usual Suspects comments on the high rates of advanced degrees among police officers in Minnesota. He cites a bit of the criminological research literature on the effects of higher education, but didn’t mention a new paper in Police Quarterly by Jason Rydberg and William Terrill.

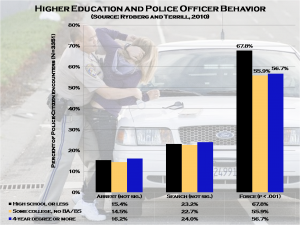

I won’t belabor the methods or Project on Policing Neighborhoods data source, but I graphed the main finding above: relative to less-educated officers, those with college experience are significantly less likely to use force in police-citizen encounters. About 56 percent of interactions with college-educated officers involved force, while about 68 percent of encounters with non-college-educated officers involved force. This relationship holds up (p < .001) in models that adjust for age, experience, suspect characteristics, and the setting of the encounter. In contrast to the use of force, defined here as “acts that threaten or inflect physical harm on citizens,” there appears to be no relationship between education and arrest or search behavior.

Even with a nice set of statistical controls, one could interpret these findings as the result of self-selection processes — that is, there might be something about the type of people who go to college (rather than the college experience itself) that results in less force by officers. Plus, force is difficult to measure and, if I’m interpreting them correctly, these levels look suspiciously high.

Nevertheless, the basic finding has now been replicated across a number of data sets and research settings. Why haven’t we required all officers to hold advanced degrees? The old arguments involve the desirability of recruiting less-educated former military personnel, while the new arguments involve the desirability of recruiting a less-educated but more diverse force. The enduring argument, I suppose, involves costs: if we require all officers to have a college degree, we might have to pay them more.