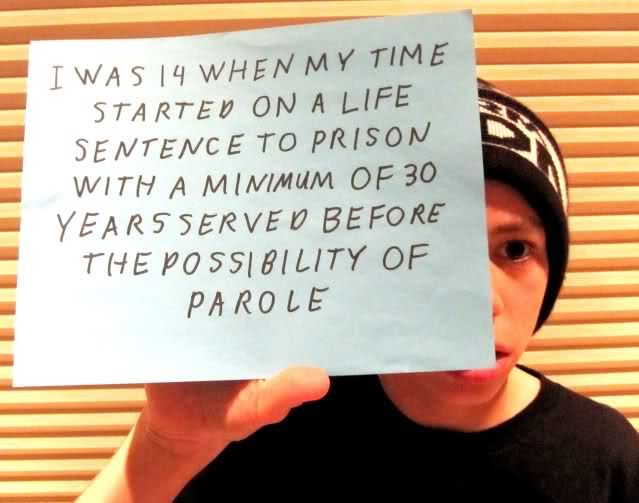

I’ve been teaching and taking college students into both “adult” state prisons and juvenile correctional facilities for a number of years now. One thing that always stands out is how very young many of the men in prison were when they committed their crimes. In a visit with the penitentiary’s Lifers Club, I could look around the room and see former students of mine who were 14, 15, and 16 at the times of their crimes and have been or will be locked up for most of their lives. The photo above is from the tumblr site, “We are the 1 in 100” that my students and I created to represent perspectives from those inside of prison and those affected by the prison sentences of their family members, friends, and classmates. The sentiment was written by one of my inside students, based on his own experience (although the card is held by a young man on the outside). He was convicted as an adult at age 14 and sentenced to a minimum of 30 years. He’s about 10 years into his sentence now, and he is a remarkable young man – smart, motivated, driven to do something meaningful with his life. I’ll be working with him again this fall, and I’m looking forward to what he can teach me and my other students.

I’ve been teaching and taking college students into both “adult” state prisons and juvenile correctional facilities for a number of years now. One thing that always stands out is how very young many of the men in prison were when they committed their crimes. In a visit with the penitentiary’s Lifers Club, I could look around the room and see former students of mine who were 14, 15, and 16 at the times of their crimes and have been or will be locked up for most of their lives. The photo above is from the tumblr site, “We are the 1 in 100” that my students and I created to represent perspectives from those inside of prison and those affected by the prison sentences of their family members, friends, and classmates. The sentiment was written by one of my inside students, based on his own experience (although the card is held by a young man on the outside). He was convicted as an adult at age 14 and sentenced to a minimum of 30 years. He’s about 10 years into his sentence now, and he is a remarkable young man – smart, motivated, driven to do something meaningful with his life. I’ll be working with him again this fall, and I’m looking forward to what he can teach me and my other students.

At the same time, for the past 6 years, I have taught Oregon State University’s incoming freshmen football players in a summer bridge program designed to help them make a smooth transition to college and the accompanying responsibilities. Every summer I have arranged to take them to one or more of our state prisons and juvenile correctional facilities to talk with inmates, see the institutions, and to get outside of the classroom to learn about social problems. It is easily the most impactful experience of the class.

It’s generally the case that at least a few of my student-athletes in the summer have not yet turned 18. I make an effort to talk to their parents and to ensure that I get waivers signed before our field trips; parents seem to trust that if a woman like me can spend that much time in prison, their young and often very large sons will probably be okay.

So here’s the irony…the maximum-security prison will not allow my 17-year-old students to visit/tour the facility and meet the inmates. I’m not entirely sure of the reasoning – the waiver releases the Department of Corrections of responsibility should any incidents arise (although they never have) and parents sign on behalf of their minor sons. Perhaps, the prison administration does not want minors to be exposed to inmates and the harsh realities of prison life. Yet, the young man convicted at 14 has lived in that very prison for a number of years. How can we possibly treat 17-year-old college students as incapable of making a decision about a 1-day experience, yet judge young teenagers as fully responsible for their criminal behavior.

The debate about life sentences for juvenile offenders is both important and timely. Perhaps with a fresh look, we can critically evaluate the accumulated evidence (including the emerging data on brain development and maturity) and create new, thoughtful, considered sentencing structures and policies for juvenile offenders who have committed serious crimes.

Comments 5

a — August 17, 2012

I'd love to have more information on brain development and maturity studies if you have the time to share them with us.

Michelle Inderbitzin — August 26, 2012

Thanks for the comment. The person whose work I have relied heavily on in learning about adolescent brain development is Laurence Steinberg. He's a prolific researcher/writer, and he has links to many of his published articles on his website: http://www.temple.edu/psychology/lds/publications.htm

He also wrote a very short piece in a recent NY Times debate on "When Do Kids Become Adults": http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/05/28/do-we-need-to-redefine-adulthood/adulthood-what-the-brain-says-about-maturity

Hope you find this information interesting and helpful!

JT — September 26, 2012

If you're going to use the brain development argument, you might as well argue that 24-year-olds shouldn't be in the same prisons as those aged 25+, seeing as how brain development continues well into your mid twenties.

I agree that a 14-year-old convicted of robbery, or a 15-year-old who shot somebody who had been bullying him for years (whether that be a peer or a guardian) shouldn't be given life behind bars. But then you have people in their thirties, forties and fifties whose brains never reach the development of the average 18 or 25 year olds' brain. People are versatile.

I don't think that all juveniles should be exempt from life in prison. Some people are just plain sociopaths, some people cannot be rehabilitated. There is no difference between a 17-year-old cold blooded murderer and an 18-year-old cold blooded murderer, despite the new law trying to get those 17-year-olds eligible for parole. Just as there are 15-year-olds manipulated and pressured into murder, there are individuals in their twenties who were manipulated and pressured into murder. There are so many different factors you have to consider. The only difference is that it's easier to manipulate a 15-year-old, but people mature (and stop maturing) at different rates.

If you were raised in an impoverished neighborhood, got involved with a gang, you are just as stuck in that lifestyle as a teenager as you are as a young adult. You don't break away from abusive and manipulative family members or rolemodels the day you turn 18. The key is to differentiate between the crimes first, but still take the offenders' ages into consideration (not only if they are juveniles). But if you stab somebody to death without second thought you are just as much scum at 14 as you are at 85. Sociopaths remain sociopaths. You can't save everyone. The stance that absolutely no juvenile murderer should get life in prison is just as extreme as saying that every juvenile murderer should get life in prison.

Inga — November 11, 2012

HI Michelle: stumbled upon your site while writing a policy brief for graduate school on the Juvenile Justice Accountability and Improvement Act. Wondering if you're familiar with The Beat Within? I was the program director there before starting school this fall. Thanks for your work and attention to such a great group of youth (those incarcerated!).

www.thebeatwithin.org

Inga

Diana — November 19, 2012

I actually think that life sentences for anyone regardless of age should be limited to the most serious crimes if not eliminated completely. It is true that some people are mentally inept that they cannot be rehabilitated but these people belong in mental hospitals, not in prisons where the harsh realities of prisons is less safe for their physical and mental health. Most inmates, after a long period of time in prisons would be better off out in the real world for not only themselves but for the public as well. A life sentence costs approximately a million dollars which is a million dollars coming out of the public's pocket. Many inmates are young men (majority African-American) who made mistakes in their youth but because they are rotting away in prison, can't do anything to create a life they could achieve if out of prison. If programs in prisons attempting to rehabilitate criminals could be established, I personally think that life sentences should be significantly decreased or even eliminated completely.