chris and i have both posted on this blog about the demonization of sex offenders (as a side note: in the reincarnation of pubcrim II, he’s now shown as the author on some of the things i’ve written — he’s too polite to say, but i suspect he may cringe at some of my opinions which are now attributed to him). yesterday’s “modern love” column in the new york times offered an interesting glimpse into a side of accused sex offenders that we rarely consider.

chris and i have both posted on this blog about the demonization of sex offenders (as a side note: in the reincarnation of pubcrim II, he’s now shown as the author on some of the things i’ve written — he’s too polite to say, but i suspect he may cringe at some of my opinions which are now attributed to him). yesterday’s “modern love” column in the new york times offered an interesting glimpse into a side of accused sex offenders that we rarely consider.

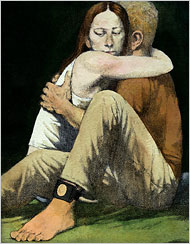

ashley cross, the author of the essay “i fell for a man who wore an electronic ankle bracelet,” dated a young man accused of raping a friend at college. she describes him and his version of the event:

Almost all of his close friends were girls. From what I knew, he had a strong relationship with his parents, who were progressive and intelligent and nurturing. He was a rule follower, a brilliant and dedicated student, a chronic people pleaser. He had a history of serial monogamy. I simply couldn’t reconcile the smart, gentle guy I knew with this startling revelation.

As I peppered him with questions, he talked me through the fateful night of only a few months before, when he and the girl, who’d been a friend, had mingled at a party and drifted off drunk together before winding up back in her room, where, several hours later, they had sex. She became hysterical, claiming he forced himself on her. He left, bewildered and distraught. That night he wrote her a letter apologizing for upsetting her and left it at her door. He told me the letter was an attempt to salvage the friendship.

“Did you rape her?” I asked.

“We had sex,” he said. “But I didn’t mean to hurt her, no.”

he accepted a plea bargain and was sentenced to 18 months of house arrest and required sexual offender rehabilitation. ms. cross describes how the stigma of his sex offender label and his efforts at “rehabilitation” changed him:

Already he felt the shame of the charge and conviction. With the sexual evaluations, he was forced to question the normalcy of his impulses. Now the rehabilitation extinguished the remaining spark he had left, the irreverence I’d originally fallen in love with, replacing it with a generic “respect” for others that in reality was a kind of bland and suffocating politeness…

Yet what alarmed me was not some sinister side of him I never saw but a passivity and retreat that I saw far too much of. In the end, I found it harder to love an emasculated boyfriend than one accused of rape…

But I’ll always regret what might have been. His ordeal will always haunt me. In my mind, he was not seeking to humiliate and subjugate a woman on that night many years ago. I believe he was a boy who endeavored for hours in the dark to express his drunken, fumbling desire in a way that, fair or not, ended up unraveling his life. I wish he had found me first.

i’ve noticed that my inside students talk about “when they fell” or the one mistake that sent them to prison. they know they have changed while serving time, but they are not yet sure how. while none of them are sex offenders, they know the stigma of being an ex-felon will follow them out of the prison’s gates. we should remember, too, it may be equally difficult for their loved ones to adapt to the changed men that return home.

Comments 2

Anonymous — January 16, 2007

The NYT piece drew some attention from one of the Kos diarists who dug up some additional detail. Especially illuminating were the happenings that got summed up in "winding up back in her room." I don't quite know what passed for sex in this case but what happens when the stigma (and all the psychological work going on inside the person and among those imposing it) diverts attention away from acts that set in motion the fall from grace?

michelle inderbitzin — January 16, 2007

thanks for the comment. i haven't heard any further details on this essay/case, but it was definitely a provocative piece. whatever happened on that particular night ended up being devestating for a number of people. for me, it's a useful reminder that the "collateral consequences" of just about any crime extend well beyond the single victim and offender -- loved ones on both sides feel the repercussions long after the event.