From an angry tweet to an actual change.

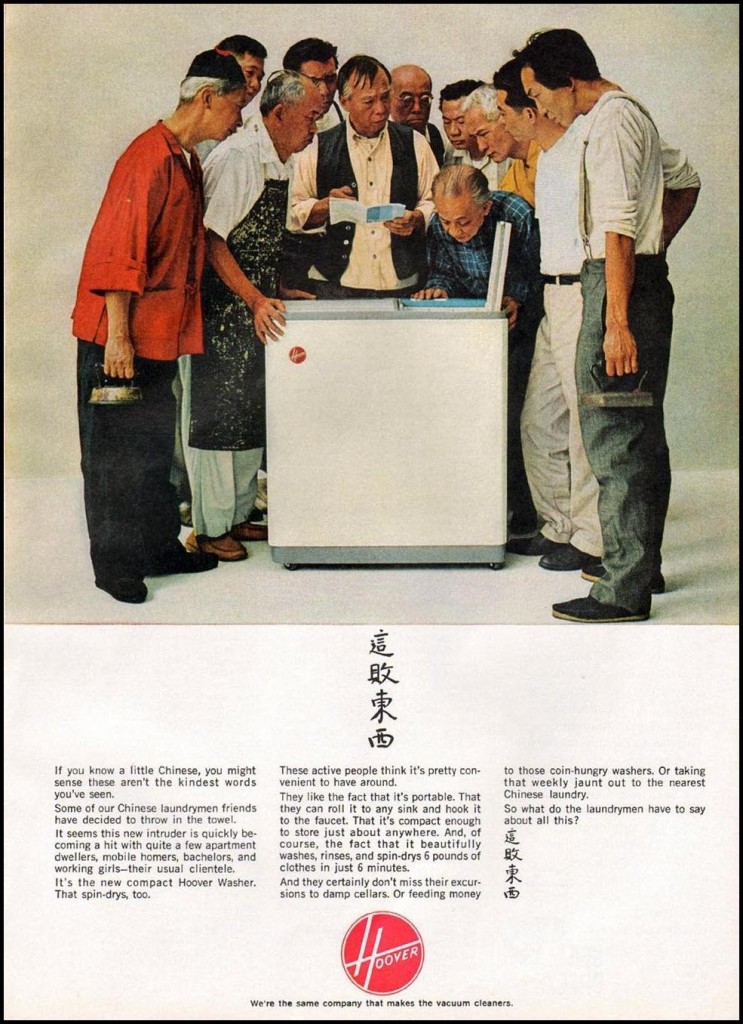

On September 1st I objected to the description of the Disney movie Pocahontas at Netflix. It read:

An American Indian woman is supposed to marry the village’s best warrior, but she years for something more — and soon meets Capt. John Smith.

I argued that, among other very serious problems with the film itself, this description reads like a porn flick or a bad romance novel. It overly sexualizes the film, and only positions Pocahontas in relation to her romantic options, not as a human being, you know, doing things.

Other Disney lead characters are not at all described this way. Compare the Pocahontas description to the ones for a few other Disney films on Netflix:

The Hunchback of Notre Dame. “Inspired by Victor Hugo’s novel, this Disney film follows a gentle, crippled bell ringer as he faces prejudice and tries to save the city he loves.”

The Emperor’s New Groove. “In this animated Disney adventure, a South American emperor experiences a reversal of fortune when his power-hungry adviser turns him into a llama.”

Tarzan. After being shipwrecked off the African coast, a lone child grows up in the wild and is destined to become lord of the jungle.”

Hercules. “The heavenly Hercules is stripped of his immortality and raised on earth instead of Olympus, where he’s forced to take on Hades and assorted monsters.”

I picked these four because they have male protagonists and, with the exception of Emperor’s New Groove which has a “South American” lead, the rest are white males. I have problems with the “gentle, crippled” descriptor but, the point is, these movies all have well developed romance plot lines, but their (white, male) protagonists get to save things, fight people, have adventures, and be “lord of the jungle” – they are not defined by their romantic relationships in the film.

We cannot divorce the description of Pocahontas from it’s context. We live in a society that sexualizes Native women: it paints us as sexually available, free for the taking, and conquerable – an extension of the lands that we occupy. The statistics for violence against Native women are staggeringly high, and this is all connected.

NPR Codeswitch recently posted a piece about how watching positive representations of “others” (LGBT, POC) on TV leads to more positive associations with the group overall, and can reduce prejudice and racism. This is awesome, but what if the only representations are not positive? In the case of Native peoples, the reverse is true – seeing stereotypical imagery, or in the case of Native women, overly sexualized imagery, contributes to the racism and sexual violence we experience. The research shows that these seemingly benign, “funny” shows on TV deeply effect real life outcomes, so I think we can safely say that a Disney movie (and its description) matters.

So, my point was not to criticize the film, which I can save for another time, but to draw attention to the importance of the words we use, and the ways that insidious stereotypes and harmful representations sneak in to our everyday lives.

In any case, I expressed my objection to the description on Twitter and was joined by hundreds of people. And… one week later, I received an email from Netflix:

Dear Dr. Keene,

Thanks for bringing attention to this synopsis. We do our best to accurately portray the plot and tone of the content we’re presenting, and in this case you were right to point out that we could do better. The synopsis has been updated to better reflect Pocahontas’ active role and to remove the suggestion that John Smith was her ultimate goal.

Appreciatively,

<netflix employee>

Text:

A young American Indian girl tries to follow her heart and protect her tribe when settlers arrive and threaten the land she loves.

Sometimes I’m still amazed by the power of the internet.

Adrienne Keene, EdD is a graduate of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and is now a postdoctoral fellow in Native American studies at Brown University. She blogs at Native Appropriations, where this post originally appeared. You can follow her on Twitter.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.