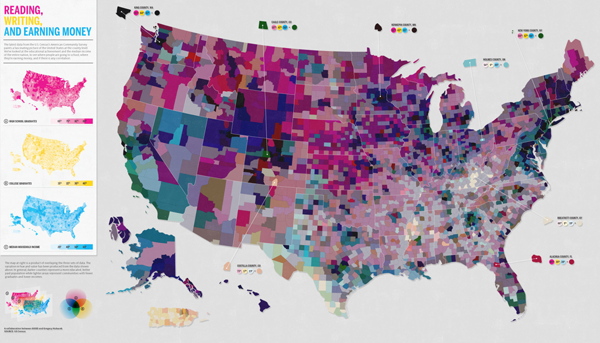

What works

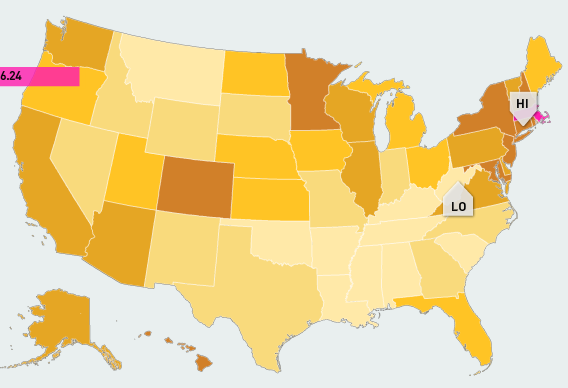

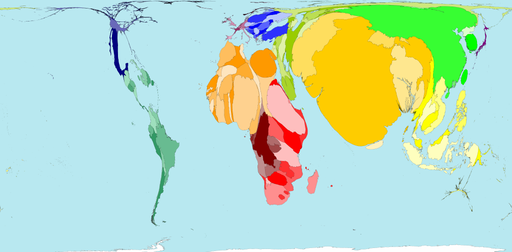

It’s a fun Friday post. Pull the slider to the right and watch the center of the US population move to the left (west) and south. What I like best about this is the interactivity. If it were just a static connect-the-dots it wouldn’t stay in your mind the way it does when you are the one doing the pulling of the slider. Getting those muscles involved, however minor their involvement might be, works more of your brain than if only your eyes were doing the work. My second favorite thing is more brain than brawn – the Census people found a way to remind us that in the beginning of our nation, we had fewer states. We added them as we went – almost always adding states to the west – so that can help explain why the center of the population originally started sliding leftwards. It has continued to slide leftwards (and towards the south) because those newer states have some lovely living conditions to offer. Not everyone loves the snow and ice of New England winters or the hurricanes of the southeastern seaboard.

What needs work

The center of population is a composite ‘score’ which tells us virtually nothing about why people are moving or where they are moving to…clearly, Missouri is not now a hotspot for internal migration. But if you were a school kid trying to grok the concept of the center of population, you might easily conclude that Missouri is a populous state.

I might have added some indicator of population sizes across US regions (state by state would be too confusing, but lumping by region would be fine).

References

2010 US Census. Center of Population