What works

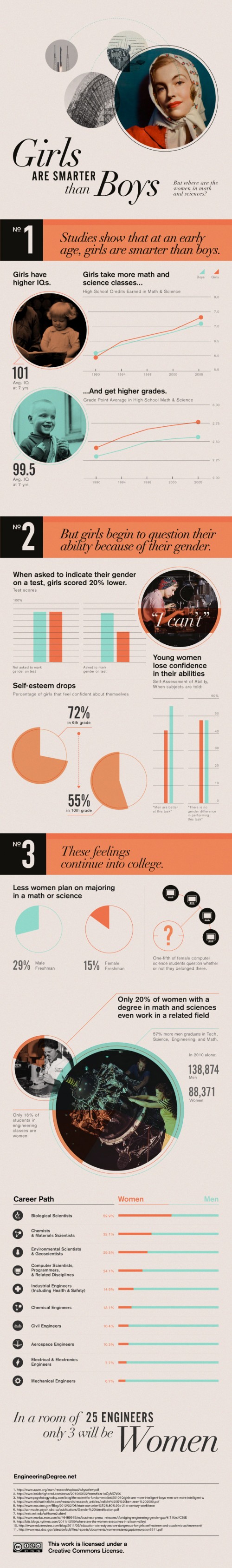

It works to start with a provocative question.

They make good use of the vertical layout by building in a vertical pagination. It’s a decent way to make a graphic web-friendly, narrative in structure, but with enough structure that it doesn’t suffer from the ‘infinite scroll’ phenomenon in which a person can get lost in a band of information lacking delineation of any kind.

The career path graphic in No. 3 is a great use of a hybrid table/graph display that does a good job of indicating how gender and major interact.

It works to compare the descriptive statistics about girls to the same statistics about boys. This graphic mostly includes girl/boy comparisons (see No. 1 and two-thirds of No. 3), but in some cases it only presents statistics about girls. For instance in No. 2 we see that girls don’t do as well on exams when they are asked to indicate their gender. Are boys the same? This particular piece of data needs more context before I would feel as though I properly understand the correlation. If girls do not mark their genders is it as if they have set gender aside for a moment and were able to take the test without remembering to ‘play dumb’? Or do they feel that they are trying as hard on either the gender-marked or the non-marked test but they do more poorly without deliberately playing dumb? Does everyone – male or female – feel more pressure the more their tests are associated with markers of identity like gender and therefore maybe all of us do worse the more we have to disclose about ourselves? Bottom line: the least they could have done was included the male comparison for all of the data points.

What needs work

I’m not a huge fan of the pictures. They imply that this is an old-fashioned problem, and I suppose it is a rather OLD problem, but it has significant contemporary impacts. I’m also not convinced that any images would have added to the information component so perhaps this is a case of ‘less is more’.

Some of the text is awfully small.

In general, I wish these vertical strips of individuated graphics could find a way to feel more like a single graphic and less like a curated collection of related data points.

Women in engineering majors

I’m including a snippet from the article that was accompanied by this graphic because the author was able to make a point that the graphic failed to depict which is that there are ways to make engineering education more welcoming to women. The strategies suggested here are so obvious that it’s hard to believe someone had to articulate them, but I think many people who have gone through undergraduate education know that advising is a rather haphazard affair.

More broadly, what the studies found was that “the climate of the department makes a really big difference about who’s attracted to the major, who chooses to stay in the major and eventually graduates,” St. Rose said. “The active recruitment of students is absolutely necessary. That’s a no-brainer but a lot of departments don’t do it, they just say, ‘Students will choose the majors they decide on,’ but inviting students to take an introductory course or to consider the major can really help.”

References

Hill, Catherine; Corbett, Christianne; St. Rose, Andresse. (2010) Why So Few?: Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. [Report] American Association of University Women.

Epstein, Jennifer. (2010) Attracting Women to Stem Inside Higher Ed