What works: Big picture

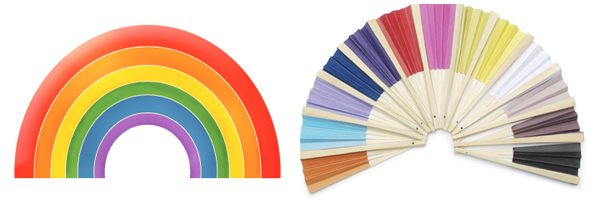

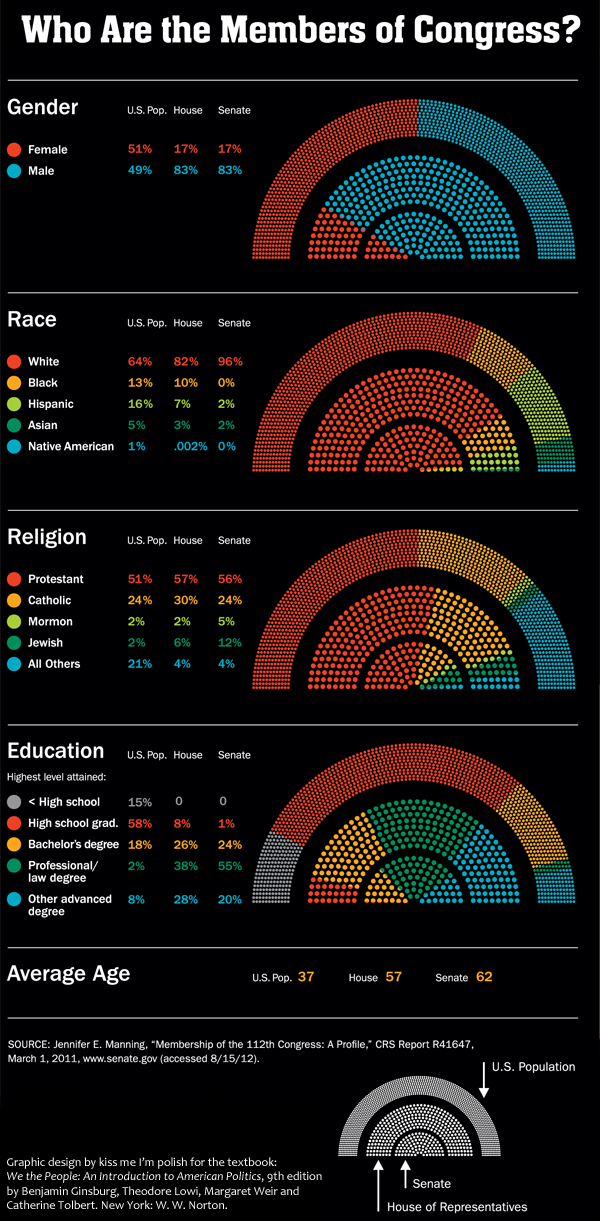

In the midst of election season, it can be easy to lose sight of the forest because we’re so entranced by the trees (or the leaves, for that matter). This graphic was developed by the design firm kiss me i’m polish in partnership with W. W. Norton and the authors of “We the People” to help students think through what it means to live in a representative democracy. The biggest outer arch of the rainbow depicts the breakdown of the total US population. So, for instance, we are split 50/50 when it comes to gender and just slightly less than half of us are Protestant. Then the middle arch illustrates how the 435 members of the House are divided and the smallest inner arch does the same thing for the 100 members of the Senate. It’s a great way to keep students thinking about not only the members of Congress but also about how that membership compares to the population they are supposed to represent.

The graphic lead me to wonder how it is that we come to collectively held opinions about what kind of parity is important. Gender parity – having about the same percentage of women in the House and Senate as we do in the general population – is a worthy goal. But age parity and educational parity are murkier. Legally, there are age minimums for serving in the House and Senate so we are never going to have age parity. I tend to agree with the founding folks who believed that wisdom and age have a measurable positive correlation, though I would probably argue that age is simply a fairly reliable proxy for experience. A young person with a great deal of life experience might be considerably wiser than an older person with very little life experience.

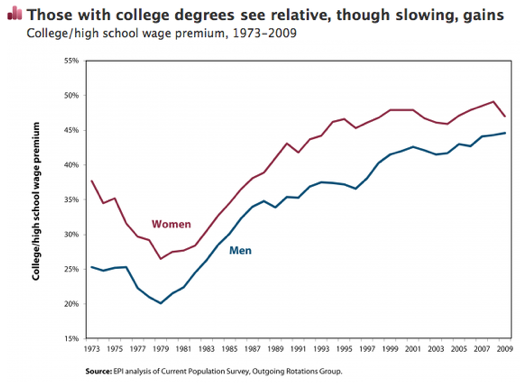

It would be easy enough to argue that we should also elect more well-educated people and feel like we are making a sensible choice as we do so. Right? More well-educated people have taken up lots of the facts and ideas circulating in a given time and place so education is probably a good thing for representatives to have. But education is correlated with class. Electing people who are overwhelmingly more well-educated also tends to mean we elect higher class folks. Of course, this is not a perfect relationship and it matters only if we think that class and political behavior are related. And, well, they are, but not in entirely linear ways, especially if education is our only proxy variable for class.

The main concern of this particular post is to show you a graphic that does an excellent job of raising fairly complicated questions without simultaneously implying answers. I am not going to push closer to any answers about how to understand the meaning of parity between individuals and their elected representatives is something we’d like to see in our representative democracy.

What works: Specific details

Color: The use of color here – especially for race – overcomes the typical tendency to try to use pink for women and maybe something dark brown for African American people. Yeah, both of those choices may make sense in some contexts, but unless there is a great justification for reinforcing stereotypes, buck stereotypes.

Fan + rainbow shape: The fan + rainbow shape is striking from a distance and allows for both segments and stripes. It offers more visual vectors for categories than I would have imagined. I probably would have gotten hung up thinking only about the stripes in rainbows and forgotten that the rainbow shape is also like a fan, and fans have segments.

Numbers are not layered over the graphic: The graphics stand on their own and the numbers are presented directly adjacent to them in small tables. This is a best-of-both-worlds approach that displays the actual numbers accompanying the impressionistic visualization of the data without having to deal with the clutter of seeing the numbers layered over or arrowing into the data which messes up the visual comparison task and also makes the numbers harder to read.

What I would have liked…

The age variable is listed as averages here, nothing visual. That’s fine, but whether or not the information is displayed just as a mean or it is developed as a graphic similar to the others, it would have been nice to be reminded that Senators have to be at least 30 and Representatives have to be at least 25 years old. This is a relevant contextual touch, helping to remind the (young) students that there are slightly different elements structuring the age disparity. Some of the extremely astute students might have been reminded that the racial category used to have a similar asterisk pointing to the role of law in politics.

References

(2012) “Who are the members of Congress?” [infographic] by kiss me i’m polish. New York.

Ginsberg, Benjamin; Lowi, Theodore; Weir, Margaret; and Tolbert, Caroline. (2012) We the people: An introduction to American politics, 9th edition. New York: W. W. Norton.

[Note: The link here goes to the web page for the 8th edition of this book but the graphic was taken from the 9th edition. A similar graphic was included in the 8th edition. The 9th edition image above includes updates that reflect the results of elections that have happened since the 8th edition was published but the overall look-feel and the design concept remained the same.]