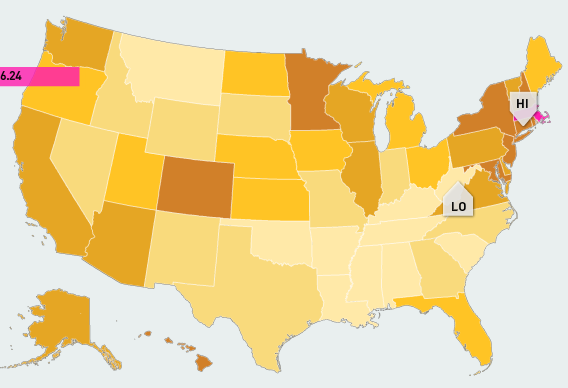

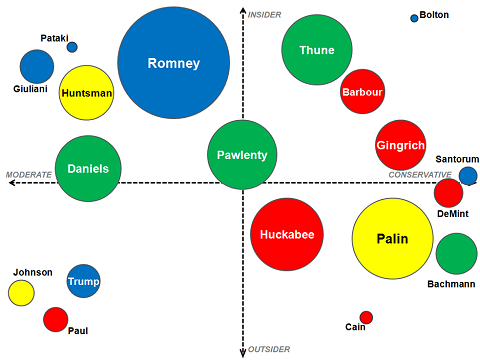

Nate Silver of 538 created this field map of the likely GOP candidates seeking the party’s nomination for President. I note, as does Mr. Silver, that none of these candidates have yet announced official intentions to run.

What works

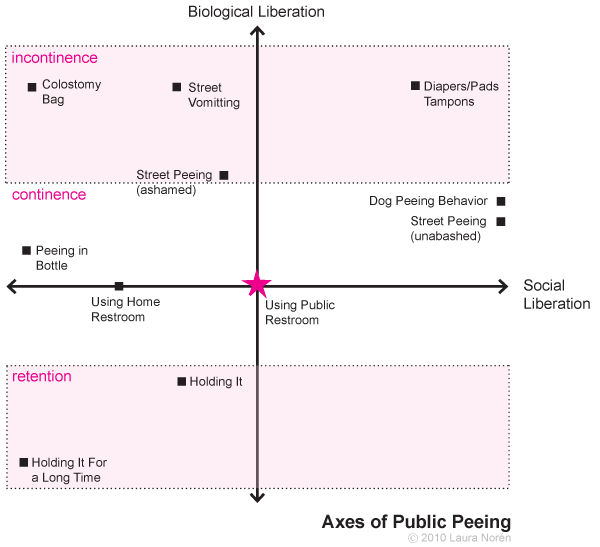

Mr. Silver and I seem to share a fondness for two-axis field maps as a way to wrangle with a pool of qualitative information. Earlier, I used the same kind of strategy to sort my thoughts regarding peeing in public.

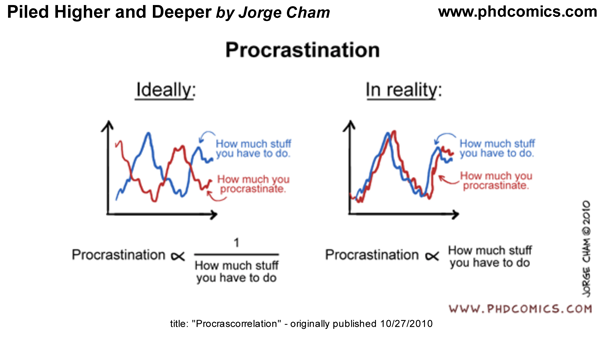

Here Mr. Silver is the field map approach (along with different sized/colored circles) to apply a system useful for thinking through the possible Republican nominees for President. As he explains, the x-axis is one of the most commonly used sorting devices for any candidate – political conservativism on the right, liberalism on the left. In this case, because all the candidates fall to the right of center, ‘moderate’ is used as the left hand label. Mr. Silver admits the y-axis need not have been the one he chose. But he decided to go with insider-outsider status because that will be an important element in this primary battle, given the claims made by the Tea Party.

The two axis field map works well for establishing some basic rules with which to sort out candidates who are attached to all manner of qualitative facts that may matter. The field map gives us a way to sort out messy, unmeasurable (qualitative, or quantitative but on different scales) information in a way that allows us a bit of clarity. If you want to use this as a tactic in your own work, I would suggest thinking through a number of different choices for axes. In this case, Silver was fairly confident about the x-axis (level of conservativism) but he was less sure that the y-axis was going to be the most meaningful compared to other choices. He didn’t discuss the other y-axes he might have considered – I can think of a few – but the point is that if you are using this approach in your own work, you need not limit yourself to coming up with one field map. In a situation like this one where you are reasonably certain about the x-axis, keep that same x-axis but redraw the field map with multiple y-axes. Maybe one of them will make the most sense. Likely they will all make some sense when it comes to explaining some things, but not as much when it comes to explaining something else. It is acceptable to end up with an array of field maps, not just one. The social world is a complicated places. Expecting it to fit into a two-axis field map is unrealistic, but helpful as a starting point.

Also, in this case, I like the use of different sized circles. The bigger the circle, the higher the odds of that candidate’s taking the nomination, according to a third party.

What needs work

I am unconvinced by the use of color. Silver himself wasn’t sure that it made sense to color-code these folks by their region of origin, but he threw in the color just because region of origin has mattered in some elections in the past. Again, if one variable doesn’t quite jive with what you think matters, I might try another. For instance, as the primary race heats up, maybe Silver would want to drop the concern with region-of-origin in favor of something like ‘attitude towards gun control’ or ‘attitude towards abortion’. Since neither of those are binary issues, he might be able to get away with using a single hue and darkening it for ardent supporters while moderate supports end up with lighter hues. Clearly, that graphic technique could be used to represent any kind of platform issue.

Further Reading

I encourage you to read Silver’s full post if you are interested in figuring out why he put the candidates where he did. No need to rehash what he has to say – he does a better job of explaining himself than I could.