What works

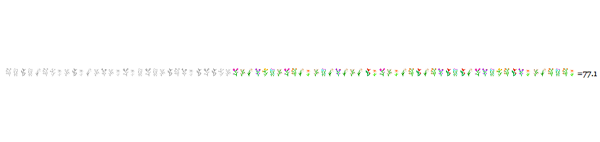

John Maeda (now head honcho at RISD, formerly of MIT’s Media Lab) designed this simple interactive graphic in 2006 while contemplating the cyclical nature of life during the still grey days of a New England winter. His visualization shows the number of springs men can expect to have if they live an average life span for men in their country. Users input their age and select their country. The flowers in color are those in the user’s future; the ones in grey represent the past. Simple. Elegant. An infographic haiku.

What needs work

I have a slightly sunnier view of the past than does Maeda, perhaps. I think I would have colored both the past and present flowers, just used different schemes. Maybe it’s the social scientist in me, but I believe our past and future both provide the context for our present. Perhaps some past years have been grey, but the territory of the past is not generally a cemetery.

References

Maeda, John. (2006) Life Counter. Interactive web-based graphic.

See also:

Maeda, John. (2006) The Laws of Simplicity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.