Kids and happiness

Thanks to my twitter feed I landed on Philip Cohen’s blog post “Children beget happiness, eventually” on his blog Family Inequality. In the post, Cohen discusses A Global Perspective on Happiness and Fertility which appeared in Population and Development Review last March.

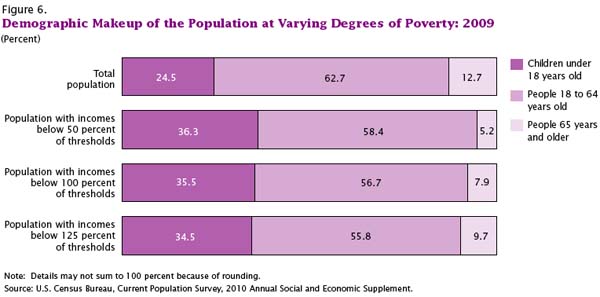

Margolis and Myrskyla used the World Values Survey from 1981 – 2005 for a total of 201,988 responses across 86 countries to perform their inquiry into the relationship between having kids and being happy. They measured happiness by asking people “taking all things together, would you say you are very happy, quite happy, somewhat happy, or not at all happy?”. They controlled for all sorts of things that probably matter like socioeconomic status, country level effects, and state welfare regimes. This is global evidence, folks, not US-only.

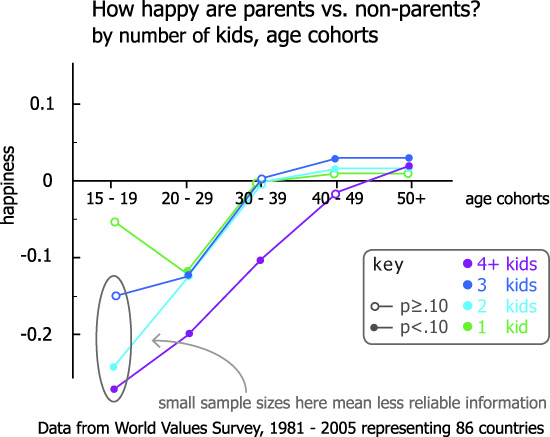

Cohen included the graph below and discussed the author’s findings which, in summary, are as follows:

1. Having kids does not lead to happiness when parents are actively involved in raising said children.

2. Older parents consistently report being happier than their childless counterparts. [My editorial comment: It is reasonable to believe that, for the most part, the children are no longer living with their parents by the time their parents start to report increases in happiness. At the very least, the kids are at least spending more time out of the home by the time mom and dad are between ages 40 and 49. The majority of kids are almost surely out of the house by the time their parents are 50+ which is the ‘happiest’ time to be a parent. Perhaps it’s because parents are proud of their kids’ accomplishments, perhaps it’s because the parents are no longer anxiously worrying about their kids well-being on a day-to-day basis. Who can say.]

3. Results in the 15 – 19 age cohort have fewer data points and are thus somewhat less representative. It’s hard to have three or four kids while in that age cohort.

An experiment

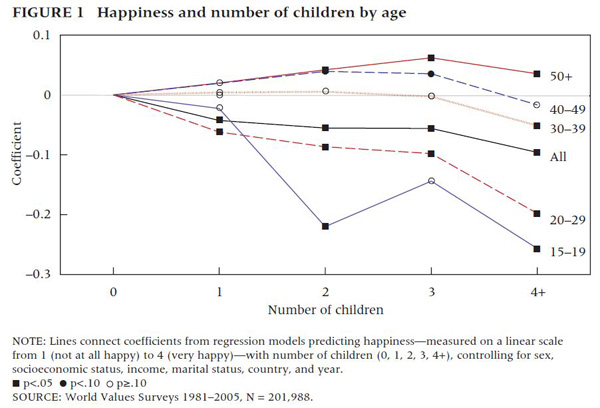

I used the exact same evidence to create the graph at the top of the blog because I wasn’t satisfied that the results were being clearly communicated by the graph above. Instead of plotting the happiness of age cohorts, I flipped it around and looked at happiness by number of children. Since I used the exact same information – pulling it directly from the graph because I couldn’t find a corresponding table in the paper – I do not have distinctly different findings to report. Duh. However, this is an excellent example of why visualizations are meaningful. It’s the same information, plotted in two different ways.

In my version, it is clearer to see that having 1 – 3 children represents extremely similar patterns of happiness across the life course. I discount the results at the very low age range because we know that the data at that end is less-than-representative. If we just look from the 20-29 cohort through to the 50+ cohort, we see that having more kids eventually represents more happiness for parents but that they are about equally unhappy during the most active years of child-rearing.

Having four or more kids breaks the pattern. This is evident in both graphic representations. In my opinion, it is more evident in the first version of the graph than the second version, as they appear in this post. I used a similar sensibility for the colors of 1, 2, and 3 children trends and a different kind of color for the 4+ kids scenario.

The graphs do not explain why having four (or more) kids would be so different than having, say, three kids. More study is needed.

My #1 take-away: do not have four or more children if you value your happiness.

My #2 take-away: Think twice about having any children at all if you would prefer to be happy for the twenty or so years it’s going to take those kids to move out.

My #3 take-away: Thanks, mom and dad. I hope you’re happy now.

References

Cohen, Philip. (14 May 2011) Children beget happiness, eventually [blog post] on Family Inequality.

Conley, Dalton. (2005) The Pecking Order: A Bold New Look at How Family and Society Determine Who We Are, New York: Vintage.

Margolis, Rachel and Mikko Myrskyla. (9 March 2011) A Global Perspective on Happiness and Fertility in Population and Development Review, Vol.37(1): 29-56.