Drug cartels cause social ills

Unless you’ve had your head in a bucket since 2007, you are at least vaguely aware that Mexican drug cartels trafficking their goods into the US have caused significant social illness in Mexico, especially in areas close to the US border. Social illness here can be measured in cartel-driven murders, but that captures only the most gruesome, sensational branches of the drug virus. Besides the deaths are fear, anxiety, mistrustfulness as well as poverty, corruption, and vast inequality.

Is mapping the right way to understand Mexico’s drug trafficking problem?

The graphics here try to pack all of the complexity and destruction of those social ills into maps. Maps are rational. They allow us to feel we have a handle on the components that make up a problem. In this case, I am sure they are not explaining the whole story. I’m also not sure they are trying to explain the whole story.

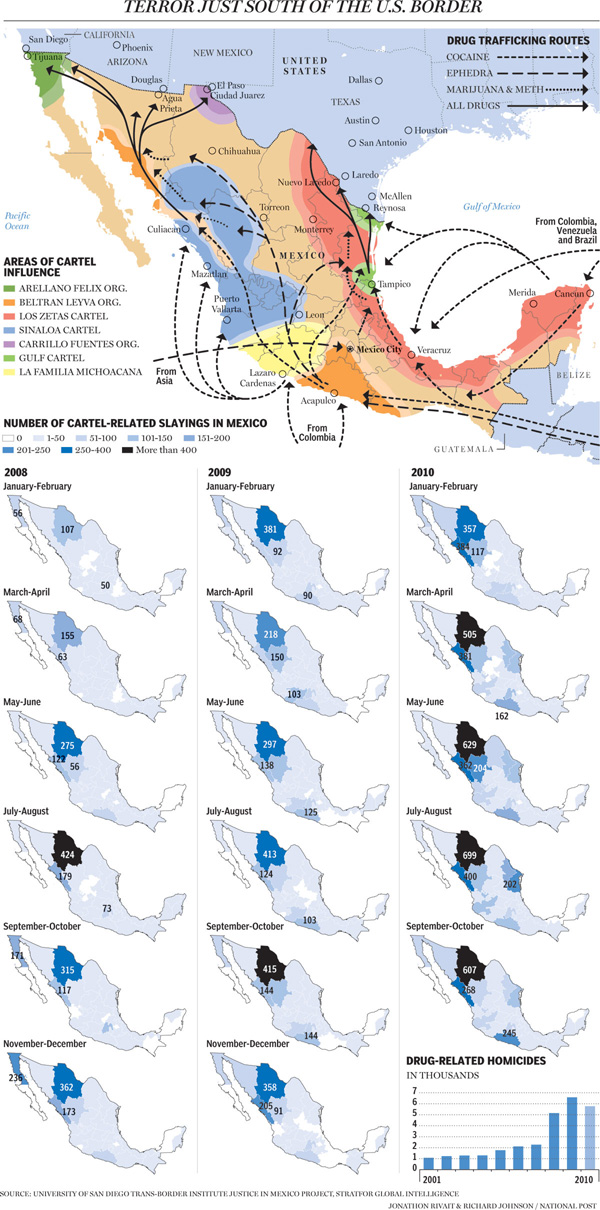

What I like about the first map is that the map makers lay out the obvious: which cartels are where. Then they go one step further and highlight the contested territory. In case the colors aren’t coming through clearly, the white areas are the disputed areas. There are a lot of white areas.

And yet…

One would expect most of the violence in a situation like this to be in the disputed areas. But that isn’t the case. Most of the violence is near the US border. The border is another kind of contested territory, one that is much more important than white areas as far as violence prevention is concerned. In fact, those areas aren’t governed by one cartel or another because those areas are not critically important to drug trafficking. None of the cartels much care.

So let’s take a look at another map because I’m thinking the first one implies that we should find violence in the middle of the country.

Drugs and deaths in Mexico

This graphic shows not only traffic patterns – where do the drugs go? – but also maps of where the deaths have been. It quickly becomes clear that the drug-related deaths are up near the US border, not in the ‘disputed areas’ highlighted in the previous map. In this map, (thanks unnamed National Post graphic designer) that undisputed area is left unclaimed and unlabeled. That’s a more accurate way to understand those regions and the inset series of maps below the main map do a good job of visually locating cartel-related violence.

The other thing I love about this map is that it specifies *which* drugs are being trafficked. Call me crazy, but I have found it odd that there is a great deal of talk about ‘drugs’ in Mexico as if there is no good reason to talk about which drugs are being moved where. Why is it useful to know which drugs are going where? First, it’s nice to know which drugs because different drugs have different price points per volume and weight. Economics matter. If one drug has a higher profit margin than another because it retails for more per ounce but doesn’t cost much more to produce/transport, one could assume that it will become more popular. Then again, demand matters, too. Even if pot is easy to produce, doesn’t mean you can convince cocaine users to try weed. They probably already tried it and moved on.

Another reason it matters which drugs we’re talking about is that detection and apprehension vary from drug to drug. An easy example: a pot sniffing dog probably won’t lead authorities to a stash of ephedra. What’s more, being able to tell where things are coming from and going to means that it is easier for authorities to target weak points in the routes. We know from news stories (I recommend looking at the LATimes, see references below), we know that drug runners pour much energy into protecting the drug routes right at the US border. But they aren’t digging tunnels under all of Mexico. There are points in the chain of drug traffic that are more vulnerable. Some of those points are deep within Mexico where it might be difficult to get well-trained, cooperative authorities with the necessary tools and manpower to perform raids.

My main gripe about these graphics is that they display this problem as a Mexican problem. This is not a Mexican problem. It is a Mexico-US problem. The demand in the US is pulling all those drugs up from south of the border. Looking at it this way helps introduce conversations about economic imbalances. I imagine that one of the reasons drugs come from Mexico is the same reason that many large companies choose not to have large labor forces in the US: labor is cheaper in Mexico. Various instantiations of poverty also tend to encourage corruption; encouraging local police to fight the cartels is hard when they are out-gunned and out-manned by cartels who can afford to pay off whoever they want including witnesses, other cops, border agents, and whoever else is likely to become cooperative after the application of a bit of grease.

Conclusion

The drug-related social illness in Mexico is an unfolding problem, one that has been discussed with more complexity elsewhere. I hope to illustrate that while the rationality of mapping patterns is appealing, it also tends to obscure complexity. It’s easier to misinform than inform with a map. They are deceivingly neat, these maps.

References

LATimes “Mexico Under Siege” special section, US News.

Llana, Sara Miller. (13 January 2011) “Mexico drug war death toll up 60 percent in 2010. Why?” in The Christian Science Monitor, World/Americas section.

National Post Staff. (31 December 2010) Graphic: Drug Terror Just South of the Mexico Border in The National Post. [Graphic].