Internet Traffic

This week we’re going to have a look at the internet. Here are two reasons why:

- 1. The not entirely superficial reason is that there are many great visualizations out there dealing with the internet, internet traffic, internet usage patterns, and so on. Many are interactive so you can play around with them yourselves.

- 2. The larger theoretical question about studying the internet and online behavior goes something like this: How much is people’s online behavior reflective of their offline behavior? Are people role-playing when they’re online, trying out personas they may not fully embrace offline (see Sherry Turkle)? Or is online behavior seamlessly integrated with offline behavior? We IM the people we’re about to have dinner with indicating that the people we talk to online are just about the exact same people we talk to offline? And if the relationship between online and offline behavior is somewhere between these two, how can we figure out just what is going on?

What Works

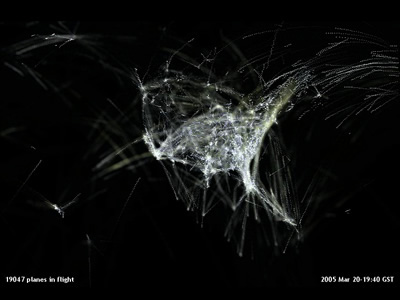

The graphic above is just a screen capture from Akamai’s site. In order to get the full impact, you have to click through and play around with it. Akamai has a slew of other visualizations you can play with that deal with network attacks, latency/network failure, retail data, news traffic, and so on.

Just to be clear, Akamai is a private company providing web-optimization services. In their shareholders’ quick facts, they say they serve up 10-20% of global internet traffic. What does this mean? It’s easy to forget that the internet requires physical structures, but this is part of what Akamai does. They maintain “40,000 servers in 70 countries within nearly 950 networks” all over the world slurping up electricity and information at about equal rates. The reason they do this is because if you are, say, a blogger in New York and you store your files on a server just down the hall (which is unlikely, but play along), if someone in Singapore wants to read your blog, the request is going to have to come all the way from Singapore to the server down the hall from you in New York and then the files will have to be sent all the way back to Singapore. This takes time, there might be network congestion along the way and if you are serving your readers in Singapore something a bit more bandwidth intensive than text (say a little clip of a new car racing around a track or a high quality music download) the person in Singapore may just lose interest before they even get the whole file. Akamai gets around this in part by duplicating files and storing them on servers all over. So if your reader in Singapore wants to access your site and you’re an Akamai customer, they will end up pulling those files from a server much closer to them, maybe in Singapore, but at least somewhere much closer than New York. Akamai’s clients tend to be Fortune 500 companies with global client bases and companies that rely on being able to transfer heavy files reliably and quickly (like music and software downloads). They do more than just the physical infrastructure, they mobilize their resources to detect net attacks, congestion, and then to re-route and avoid those things. The bottom line for us is that they make some of their knowledge of the ‘net available in these visualizations like the one above.

What Needs Work

I would love to have more granularity and access to the actual numbers and the methodology. All these shiny interactive graphical toys run the risk of being too glossy, not data-transparent enough.

Not as Shiny, Quite Helpful

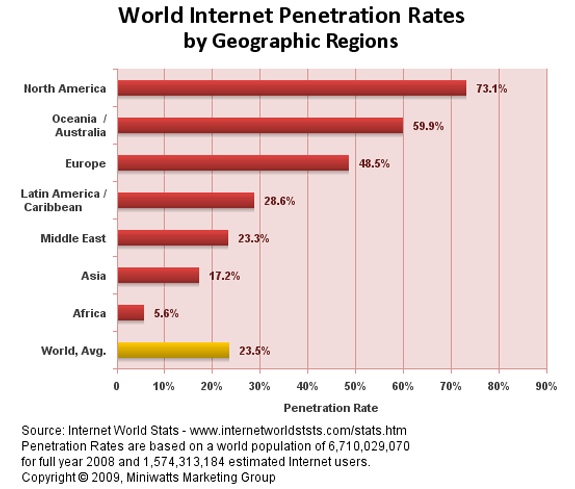

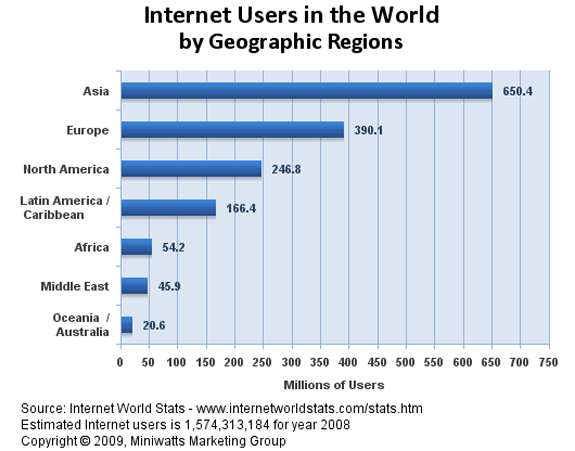

These two graphs give a quick overview of who is using the internet by geographical location. You’ll see that rates of traffic can be a bit misleading – not all continents have the same population. That’s why I included the rate of internet penetration within the continents. A low rate of penetration tells you a lot about how the digital divide which is a very real problem. More on that later this week when we will address the digital divide directly. For now, it’s enough just to notice the difference in looking at the flashy, glossy Akamai graphic and the simple bar graphs. I don’t know about you, but I quite enjoyed playing with the Akamai graphic and encourage interactivity. Still, the combination of these two bar graphs above gave me a clearer answer to the big question about who in the world has access to the internet in the first place.

Relevant Resources

The Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University School of Law.

Deibert, Ronald, Palfrey, John; Rohozinsky, Rafal; and Zittrain, Jonathan (2008) Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering Cambridge, MIT Press.

Turkle, Sherry. (1984) The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit Cambridge, MIT Press.