What works

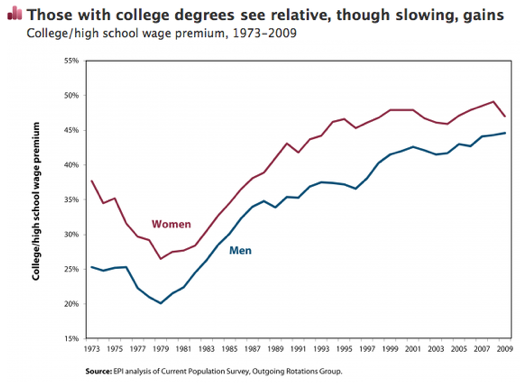

Looking at change over time is often best when using simple trend lines. They are easy for the eye to follow – easier than if the same figures were depicted as bar graphs. Given that there are measurable and meaningful differences between the returns for men and women, it is a good idea to show two separate trend lines, as they have done here.

What needs work

The major problem is that returns to college education do not come only from the education received. This trend line is a simple construction that cannot sort out how much income can be attributed to college alone. Sociologists know that a combination of factors – from parents’ educational attainment and parents’ income to things like the student’s aptitude – impact measures of the student’s attainment (like income and wealth). A far more sophisticated model would estimate just how much income one could expect, all other things being equal, for each additional year of schooling. That’s a much tougher model to construct and it wouldn’t be something that could be plotted using trendlines.

In fact, one of the big problems with trend lines is that they are often overly simplistic. On the other hand, they can be excellent representations of the big picture, whatever that might be. There is no simple rule I can think of that would help sort out when a trend line is a great idea and when it is overly simplistic. In this case, change over time is hardly the main story. The real wrinkle when it comes to education is that it can be difficult to determine if students are receiving indoctrination into social networks, ways of acting, and professional networks while they are at college and that these are the advantages that lead to the later bump in income or if they are receiving important knowledge that makes them better, more qualified workers. What’s more, even if we will never be able to divorce the networking from the knowledge gained, we still wouldn’t know how much the background a student starts school with influences their later life choices. Think about this. If someone deeply embedded in a network of people who would usually be a college attender chose not to go to college but continued to hang out with the same people and therefore received much of the same college experience, social and professional networks, how would they fare later in life? Since social scientists cannot randomly assign some students to attend college and others not to, it is very difficult to answer this question. And in this case, a trend line is an oversimplification that misses the major questions about returns to higher education altogether.

Knowing what we know about the various influences on wages later in life and what we see in the trend line, we might assume that women are better able to use educational attainment to escape lower incomes that would have been predicted by, for instance, their parents’ education and/or income. But again, the suggestion that educational attainment has some kind of positive influence on wage premiums is correct, but incomplete. Any assertion about the relationship represented by this graphic is likely to be inaccurate and certain to be incomplete.

References

Blau and Duncan’s Status Attainment Model.