What works

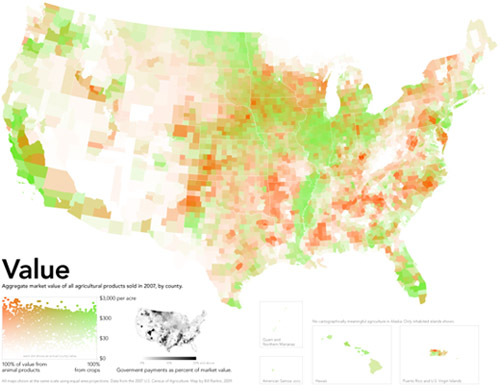

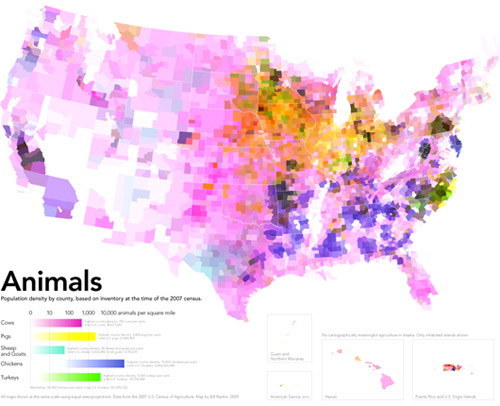

Produced by Bill Rankin, Assistant Professor of History of Science at Yale University and editor/graphic designer at Radical Cartography, these three maps work together to show how American agriculture is organized both spatially and economically. [Click through to Radical Cartography to see much bigger versions. Since that site is in Flash, I can’t embed links that take you directly to the big versions. Once you get to Radical Cartography click: Projects -> The United States -> Animal/Vegetable.] The top map here is the dollar value combination of the cropland and livestock areas in the US. For activist types, what’s even more exciting is the small black and white inset map that takes into account federal agriculture subsidies. The next two maps were combined to produce the top map – one shows how cropland is distributed, the other displays the distribution of livestock.

Bill Rankin is a rigorous researcher with a background in history and the thing he does best here is context. In order to understand the top map – which is what I believe Prof. Rankin wants viewers to store in their memory banks as the critical take-away – he first shows us how cropland and livestock land are distributed and then layers them over one another to show us how they are differentially valued. This type of data is sensitive to geography and location in two ways: 1. crops are sensitive to elements of geography like climate and available water supplies – there are no crops growing in the dessert of the American southwest 2. because the US hands out a variety of agricultural subsidies, the political boundaries of states have to be seen in conjunction with the crop distribution in order to understand how the political levers lead to the current subsidy scenario.

What needs work

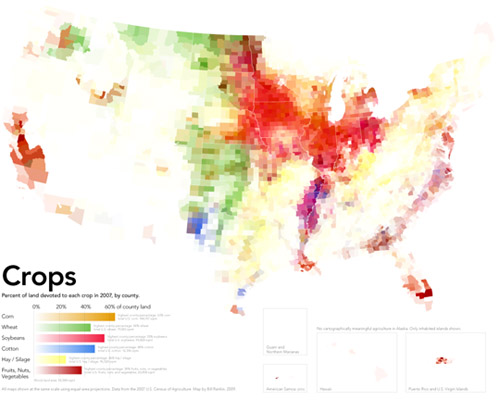

The approach he takes is to color each county based on the percentage of area covered by a particular crop. This means that counties with multiple crops will end up with blended color values. For instance, cotton is coded blue and ‘fruits, nuts, and vegetables’ are coded maroon. This means that in some southern counties growing roughly equal amounts of cotton and ‘fruits, nuts, and vegetables’ the counties are neither blue nor maroon but purple. But wait. The blue of cotton might have combined not with the maroon of ‘fruits, nuts, and vegetables’ but with the brighter red of soybeans to produce that purple color. Confused? I am. I don’t know if those southern counties are a mix of peanut and cotton farms (likely) or a mix of soybean and cotton farms (also likely).

Another problem with the additive colors is that the choice of each color has a major impact on the impressionistic take-away of the maps overall. Corn is the most prevalent crop in the US covering over 144,000 square miles. The next most prevalent crop is soybeans which covers about 100,000 square miles. Soy beans and corn are often grown in the same counties (unlike, say, wheat which is a hardier crop and therefore ends up as a monoculture in northern counties where growing corn and soy are riskier endeavors). This means that soy and corn are going to have layering colors the same way that we saw crops layering with cotton along the Mississippi River in the south. Since the bright red color for soy is more aggressive than the somewhat subdued dusty orange chosen for corn, the impression we take away from the map is that soy is more prevalent than corn where the opposite is true. If the color values had been switched so that corn was coded in bright red and soy was coded in the dusty orange, the middle section of the country would end up looking like a corn field, not a soy bean field. Either way, the trouble with blending colors is that our eyes are not very good at looking at a color and saying – “Gee, that looks like it’s about 50% blue and 50% red.” We just say, “Gee, that looks like purple”. Or, in this case, “Gee, all those reddish colors either look like soy beans or maybe an 80% coverage of the ‘fruit, nut, vegetable’ category.”

A solution (that I am too lazy to put together)

In summary, the inclination to display crop and livestock coverage using maps was a solid inclination. I often criticize the inappropriate use of maps. In this case, I still think it could have gone either way. A clever Venn-diagram that used circles based on the total coverage of each crop which then overlapped with other crops in places where they are grown together could have been more illustrative. It would have been easier to see that corn is king, for instance, and that cotton and wheat are never grown together because cotton needs heat and wheat is cold-tolerant. The same sort of Venn-diagram could have been constructed for livestock. A final Venn diagram where the size of the circles is keyed to the dollar-per-square mile value of these crops could have then displayed how agriculture functions economically.

References

Rankin, Bill. (2009) Food: Animal/Vegetable” [Information Graphic, Flash] RadicalCartography.net.