What works

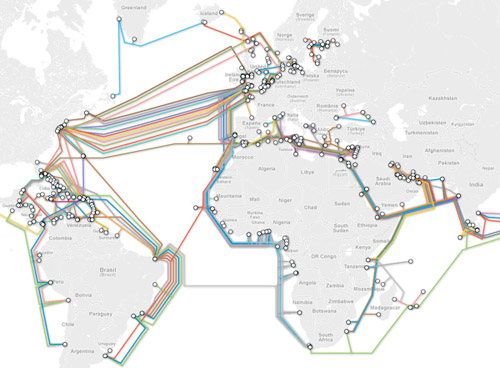

I like the colors in the graphic above, however, the version I found does not come with a key but if you click through you can see one. The internet does not always deliver material the way it was originally designed or in the way that we would prefer it.

So I went looking for the original, the one that would probably have had a key attached to it, and found this map of the same information instead.

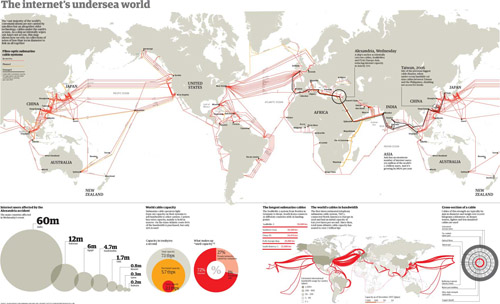

I realize it is hard to see the tiny thumbnail of a graphic so you can either click through to the full version at the Guardian or look through the images I’ve distilled from the original below.

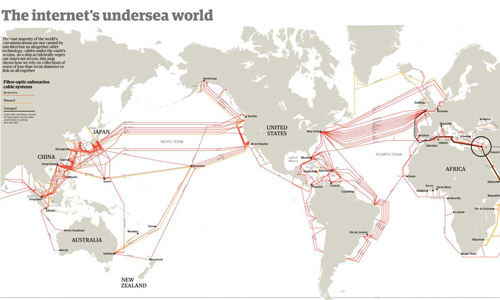

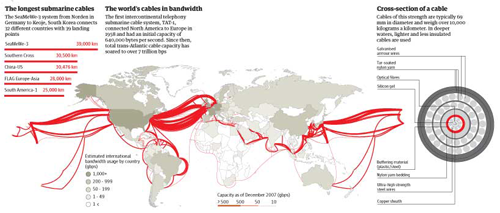

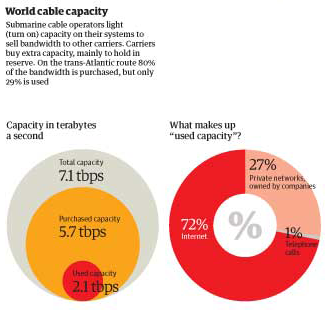

Besides the map above, which shows where all of the cables are laid out and is very similar to the colored version at the top of this post, the Guardian cartographers/infographic designers included useful contextual graphics. Often, there is much more to maps than just the map, and to fully understand why and how the geography matters, it is critical to understand characteristics of the relationship that are not available through the map alone. For instance, in the case of undersea internet cables, the paths and linkages indicate that connections between, say, New York and London are probably quicker than connections between Minneapolis and Leeds. But it is also useful to know how fat the cables are because this is a good proxy for their bandwidth. If the traffic between two points in this network approaches the carrying capacity of the cable, connections might slow down, there would be reasons to build more cables, and so forth.

The Guardian carried on with this sort of critical analysis by showing how submarine operations sell capacity to other carriers, who mostly buy it as back-up. On the busy trans-Atlantic route, 80% of the capacity is purchased but only 29% of it is being used. This kind of arrangement is in place for times when communication bandwidth needs spike far, far higher than normal and when cables are cut.

Discussion

I was turned on to ferreting out these maps by a book I’m reading by Michael Likosky called “Obama’s Bank: Financing a Durable New Deal.” In the book, Likosky points out that one strand of the global internet infrastructure was privately financed, though still heavily reliant on governmental cooperation.

He writes:

In 1995, the US West finalized an agreement fo the construction of the Fiber Optic Link Around the Globe (FLAG). This $1.5 billion project would run a fiber-optic cable from the United Kingdom to Japan. In the process, it would link up twenty-five political jurisdictions. It contributed to a series of interlacing global information infrastructure project. Although underwater telegraphic cables had been laid at the close of the previous century, this project represented the first ever privately initiated and financed transnational communications link of this size and scale. FLAG was only as strong as the public guarantees of the twenty-five licensing authorities involved in legitimizing the project. In other words, it was a transnational public-private partnership.”

I was left wondering who financed the other strands of this aquatic internet infrastructure, realizing that it was probably more reliant on the public sector than the private sector, which is why FLAG is so unique. One of the reasons this matters is that global communications connectivity makes the current trans-national spoke and hub pattern of US business development possible. Without high speed communications connectivity, it would not be feasible for multi-national corporations to situate call centers and other communications-heavy activities far from the hub of commercial activities they are supporting.

If the US Federal government was indeed responsible for some of the early undersea internet bandwidth, I wonder if they had an inkling of how that might impact the development of off-shoring. It has been argued, though maybe not recently, that off-shoring is a good thing because it puts environmentally and socially negative jobs outside of America. Then we can reap all the rewards of growth up the management chain by locating the better jobs here. Clearly, it is irresponsible to locate environmentally detrimental projects in places were regulations are lax for the sake of increasing profits here. The same argument holds with respect to social ills like poor safety standards for workers, child labor, inhumane hours, and other negative working conditions. Increasing the ability to communicate instantly with far flung places makes the spoke-and-hub pattern more possible.

What needs work

Neither of the maps show who paid for the cables or who generates what kind of revenue from their use. I really want to know. I was hoping the color-coded one might do that, but without the key it’s impossible to tell.

References

Likosky, Michael. (2010) Obama’s Bank: Financing a durable New Deal. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, Bobbie. (2008, 1 February) How one clumsy ship cut off the web for 75 million people. The Guardian, Technology Section. Map graphic by telegeography.com.