It’s the end of the semester here in Minnesota, and we here at TSP HQ are bringing in the summer with some beers and BBQ with the grad board. But don’t worry, we rounded up our amazing week for you first. We’ve got a new Special Feature on gender segregation at work, a new Office Hours podcast on financial insecurity at home, and much more below.

TSP Special Feature:

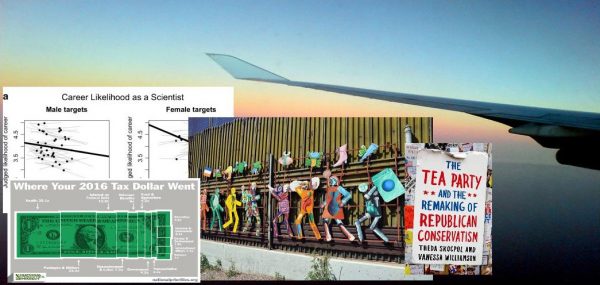

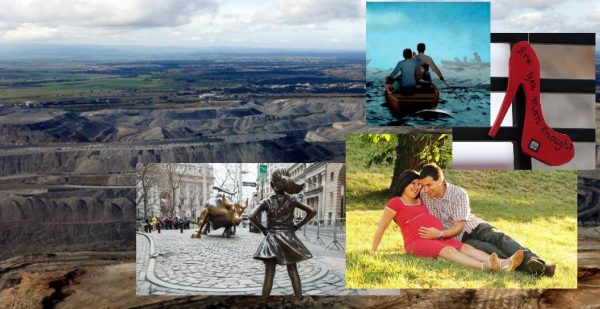

“Hidden Figures and Feud: Pop Culture Tales of Occupational Segregation,” by Robyn Ryle. In our latest special feature, Ryle draws on recent media depictions of gender segregation in science and film to reveal the socially constructed nature of gender and occupations.

Office Hours:

“Marianne Cooper on Families in Insecure Times,” with Sarah Catherine Billups. In this episode, we talk with Cooper about her latest book and the ways that families of different social classes perceive and manage contemporary economic anxieties.

There’s Research on That!:

“The Hopes and Broken Promises of Coal,” by Erik Kojola. Trump recently promised to bring back coal, but research shows that mining may not lead to the economic growth and well-being that many are promising.

Discoveries:

“How Policy Promotes Parental Happiness,” by Brooke Chambers. Parents in the U.S. are some of the unhappiest in the world, and new research in the American Journal of Sociology argues that it likely has something to do with the lack of national parental support policies.

Clippings:

“Domestic Violence Outside the Home,” by Neeraj Rajasekar. Silva Santos talks to Angelus about the links between gender violence in and outside of the domestic sphere.

From Our Partners:

Council on Contemporary Families:

“A View from Above: Social Structures + Youth’s Egalitarian Essentialism,” by Daniel L. Carlson.

Contexts:

“Fearless Girl: Seriously, the Guy Has a Point,” by Greg Fallis.

And a Few from the Community Pages:

- Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies discusses the Guernica bombing and its message for today.

- Families As They Really Are flashes back to secular listening on November 9th.

- Sociological Images exchanges questions and answers on sex and love in and after college.

- Engaging Sports talks the evolution of Muhammad Ali’s “draft dodging”.