[Caveat: The discourse around bodies with uteruses is most often framed in cis-sexist binaries of women and men. The essay below is an analysis of that discourse, and as such occasionally slips into this language to accurately present the arguments therein. Trans and non-binary people are notably missing from this discourse. I’ve tried to avoid cis-sexism where possible. Comments and criticisms are welcome whether in the comment section or by writing to me/messaging me on Twitter: @bsummitgil. I hope I have done this conversation justice.]

You may have seen the recent hubbub about 19 year old self-proclaimed meninist Ryan Williams, who recently declared that women should just hold their menstrual blood in. Specifically, they should just keep that nasty stuff in their bladder until they get to a toilet. The argument was primarily an economic one: women do not deserve free tampons (though his response was actually in regards to the movement to end taxes on tampons, not to make them free). If women are so weak that they cannot hold in, they should see a doctor to have a “procedure” that will give them the “self control” they need to stop using menstrual products, as any demand to reduce the cost of these products makes them “cheapskates.”

Williams has since set his account to private, but I can assure you that I saw these tweets personally and they have been quoted in many articles about his public display of ignorance. I cannot prove that Williams is not a troll, but he was interviewed and did not back down on his comments. At any rate, Williams is not alone in his grave misunderstanding of reproductive anatomy. A quick Google search of “can women hold their periods in” reveals… well, a lot. Some folks seem to think, like Williams, that periods come from bladders, or perhaps that there is a sphincter around the vaginal opening capable of holding in the menstrual tissue. Others think you can kinda poop it all out at once. Clearly, the health education system is failing our young people.

There is a long history of using technology to help (or, in many cases, make) women control their bodies. One of the oldest and well-known examples is that of hysteria, a condition in which a wandering uterus causes women to have uncontrollable emotional outbreaks. Obviously, these emotions were very inconvenient to men, and so, had to be treated. Ancient treatments often required hysterical women to place various good or bad smelling substances around their mouths or vaginal openings. A lack of sex and the build up of “feminine semen” could also be the culprit, so sex and pregnancy would cure hysteria. Or maybe sin and witchcraft were to blame. The cure for this was obviously “purification” by fire. Later we got to plain old masturbation, a tried and true method for relieving period cramps to this very day.

In the modern age, particularly as scientific research became more effective at regulating bodies, the processes of menstruation and pregnancy fell under the jurisdiction of technology as popularly understood today. By that I mean the ways we think about (or with) technology—not as good or bad smelling substances, but as tampons, vibrators, and hormonal birth control. Whether or not these technologies are liberating or oppressive remains hotly contested. Feminist Technology, a volume edited by Linda Layne, Sharra Vostral, and Kate Boyer, lays out many of these debates, as well as the history of and current state of technologies related to reproductive health. What makes a technology feminist? What is liberation of, or from, the body?

The foundation of many of these arguments is rooted in the Enlightenment split that characterized men as rational and civilized and women as emotional, tied more to nature. Embracing, controlling, concealing, and otherwise manipulating the “natural” bodies of people classified as women has been and continues to be the focus of much of this discourse. Science must conquer the uncontrollable effects of women’s reproductive systems. These technologies are often just as rooted in patriarchal notions of inconvenience, danger, and, frankly, “grossness,” as they are in feminist liberation from the body and social control over it.

Take, for example, the first tampon. As Sharra Vostral writes, the earliest tampons were not for menstrual application at all, but for stopping up wounds. However, when soaked in mercury chloride they could be used to treat vaginal problems, such as yeast infections or other discharges. After the turn of the 20th century, “part of displaying a modern identity for women meant managing menstruation with sanitary napkins” (Vostral, 138). But of course, these napkins were bulky and often harbored bacteria, causing infections. Tampons, or “internal sanitary napkins,” were invented—as with so many technologies—by more than one person at the same time. Two patents, one by a woman named Marie Huebsch and another by a man named Ives Marie Paul Jean Burril, were submitted in 1927. Others were submitted later by various people, and while the reasons stated for product and some basic designs varied, all served the same purpose—plugging up the menstruating vagina.

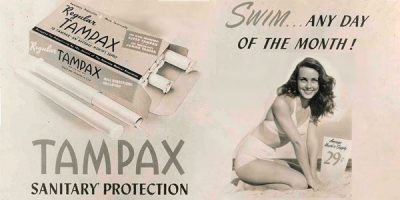

The arguments for tampons at this time were far from liberatory—tampons were developed and patented largely by men who “felt sorry” for women who had to endure menses, and to keep things like bed sheets and clothing free from staining. The inventor of Tampax, patented in 1931, said he “just got tired of women wearing those damned old rags” (Vostral 139). The lack of feminist design in these tampons (ex: being difficult to remove), and the market-driven forces that made them profitable (the use of cheap synthetic materials) led to many problems with their use. Infection, pain, and Toxic Shock Syndrome were common.

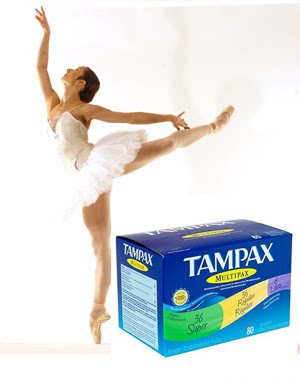

Later, as feminism became more widespread in public discourse, tampons were re-scripted as a liberating technology, particularly in advertising. This narrative endures in commercials featuring women swimming and playing soccer, or wearing white skirt suits to very important professional meetings. The shame of having a visible period stain in public continues to play a prominent role in advertising, and in the larger public discourse around menstruation.

Ecofeminist arguments against disposable sanitary products also rose around the time that tampons became “liberatory.” The environmental waste created by them, and the risks they posed to women’s health, catalyzed the popularity of other methods such as menstrual cups and reusable sanitary products. However, these technologies continue to lag behind disposable products, largely due to the stigma of direct contact with menstrual blood and tissue.

Myriad other technologies—birth control, breast pumps, home ovulation tests, and insertable devices to prevent pregnancy—are caught within the narratives of liberation and control. Newer products like Thinx period panties work to moderate between those notions. Thinx “protects you from leaks and keeps you feeling dry” because “every woman deserves peace of mind.”

Control and liberation are not opposing narratives; they are inextricably bound up in one another. Liberation movements are often spurred by the desire to have more control over one’s life and happiness. I doubt many people who menstruate would enjoy being restricted to bulky rags and unsanitary sanitary pads. Personally, my menstrual cup has completely changed my relationship with my period. If I could, I’d choose to never menstruate again, but even if I could find a doctor willing to perform one of the available procedures, they often have terrible side effects. Or, I’d choose to just “poop it out” all at once, as some people believe is possible. Or I’d simply “hold it in” until I find a convenient time and place.

Obviously, those of us who menstruate cannot do these things. We have to find other methods to control our menses. But control for whose sake is an important question. Are we taking control of our bodies for our own happiness, or for others? The never-ending push for better menstrual products is not only for the person who menstruates, but also for the person who wants to be protected from the reality of menstruation—the person who cannot bear the very idea of, let alone the visceral sight of—menstrual blood. It is, in part, the stigma that drives innovations in menstrual technologies. The individual has what amounts to a moral responsibility to hide their menses from the world. The result of this moralizing discourse is a young man on Twitter who thinks that women who can’t “hold it in” until they reach a toilet don’t deserve tax-free tampons. They’re weak, and that is “not the tax payer’s problem.” After all, in his words, “it’s all about self control.”

Britney is on Twitter.