On May 13, 2016 the Obama administration issued a letter of guidance concerning the protection of gender identity in school housing, restrooms, and locker room facilities under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. The letter was largely seen as a reaction to a March 2016 law passed in North Carolina, HB 2 – Public Facilities Privacy and Security Act, which limited public restroom use to one’s assigned at birth gender. On August 21, 2016, however, a Texas U.S. District judge blocked the federal government from implementing that directive, instead arguing that Title IX aimed to “protect students’ personal privacy, or discussion of their personal privacy, while in the presence of members of the opposite biological sex.” The district court applied a similar logic to HB 2 in arguing that gender identity was strictly “biological” (e.g., what one’s birth certificate says).

The district court ruling, in line with several others this year, relies on and perpetuates a number of transphobic beliefs which seem apropos to mention here, namely: a normalized definition of biological sex, the notion of trans bodies as illegible, impure, or incomplete, the forced hypervisibility of trans bodies through constant surveillance, the public fixation on genitalia as a ‘true’ indicator of gender identity, and the displacement/occlusion of responsibility for anti-trans violence. It is, in particular, the contemporary mobilization of a politics of shame, manifest through the aforementioned practices, however, that I would like to hone in on.

The 20th century psychologist Silvan Tomkins wrote that “like disgust, [shame] operates only after interest or enjoyment has been activated, and inhibits one or the other or both. The innate activator of shame is the incomplete reduction of interest or joy.” To Tomkins, shame emanates from the “introduc[tion] of a particular boundary or frame” to one’s own pleasures through their perceived strangeness. There is, in effect, then, an out-of-place-ness endemic to shame, in which enjoyment is not simply denied, but heinously reconstructed as emotional and psychical violence. As Eve Sedgwick elucidates, “the pulsations of cathexis around shame, of all things, are what either enable or disenable so basic a function as the ability to be interested in the world.” Thus, shame is at once a spatial and affective regime with profound psychic and ontological implications.

To wit, Dean Spade has argued that alongside government IDs and access to health care, institutional sex-segregation has an outsized impact on trans people’s lives. One need only engage in a cursory online search to find countless stories of anti-trans humiliation, bullying, and violence. To marshal Tomkins’ definition of shame, then, is not to say that all trans people display a kind of abject sexualized pleasure around bathroom acts, but instead that the bathroom is an especially charged affective site in which the becoming of gender is constantly contested. The strict parameters of biological gender specificity at the bathroom, under the guise of “protection” (both materially and discursively) affixes shame to a site that held the possibility for validation and enjoyment. This is, importantly, a kind of loss not characterized by an ever-unattained lack of “true” gender identity, but rather a recognition of self-expressive joy twisted into self-doubt.

It is no accident, then, that much of the current popular media discourse around transgender rights is localized in the bathroom. Anne McClintock has asserted that the public bathroom of the Victorian era was part of a gendered politics of hygiene, in which middle class women were expected to be clean and respectable at all times. Concomitant with this newly intimate public were a range of anxieties over women’s bodies and how to keep them ‘pure.’ As McClintock avers, “The iconography of dirt became a poetics of surveillance, deployed increasingly to police the boundaries between ‘normal’ sexuality and ‘dirty’ sexuality.” The bathroom, therefore, became a disciplinary site (one among many) in which proper femaleness was simultaneously constructed and policed, with shame affixed to deviance from ‘the norm.’

The bathroom also has a rich queer genealogy. As Shiela L. Cavanaugh contends in Queering Bathrooms, public restrooms have gender normativity built into their very architecture, “bathroom architectures are based upon vertical lines and a wish to straighten things out…This verticality consists in obstinate repression of the abject, the unclean…the horizontal…along with visibly queer and/or trans people.” In a similar vein, Jose Munoz writes of Leroi Jones’ (Amiri Baraka) one act play The Toilet (1964), and its violent intersections of race and queerness. The play stages a fight between a white boy and a black boy in a high school restroom (the contemporary segregation of bathrooms should also not be forgotten here) who we come to learn have a sexual, if not romantic relationship. While Munoz reads the play for its connections to violence and futurity, it also highlights the bathroom as a space of queer performativity and voyeuristic surveillance, as a group of boys has come to watch the fight unfold. In Jones’ play, the bathroom, a site of strict gender roles, is staged as a place of identarian instability, racial tension, and an unfolding queer shame made visible to the public.

Today, we find that much of the same anxieties haunt the language of legislations like HB 2 and political rhetoric embraced by transphobic politicians and TERF activists alike. At stake, in their minds, is both the respectability of (cis) women (under the guise of their ‘protection’) and the legibility of a gender binary that ensures a continued mechanism of hierarchical control. In this line of thinking, espoused by those like anti-trans ‘feminist’ academic Sheila Jeffreys, biological indicators of sex act as “scientific” markers of truth that legitimate transphobia. Genitals, in particular, are fixated on and fetishized as indicators of “objective” legibility that must be seen and either mocked or validated. As Julia Serrano reminds us, “constantly being reduced to our body parts,” seeks to constitute the trans body as partial or incomplete. This is a kind of boundary making that Tomkins alludes to, a wholesale denial of being/pleasure through shame of one’s body, made visible to the public at large.

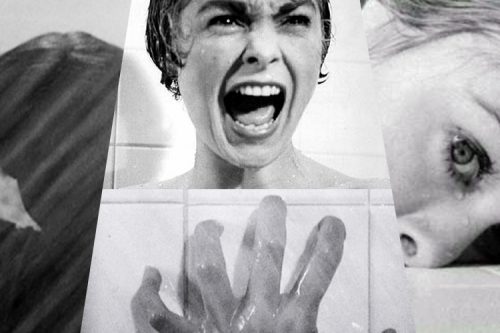

Nowhere is this one-two punch of anxiety and shame made more apparent than in the bathroom worlds of horror cinema. From Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho to David Cronenberg’s Shivers to Wes Craven’s Nightmare on Elm Street, the bathroom has long been staged as a site in which female sexuality is both surveilled and policed. What is ostensibly supposed to be a space of privacy is perforated in these films not only by the camera itself (the complicity of voyeurism highlighted by Hitchcock in Psycho’s famous shower scene or mirrored to a schlocky absurd in the opening film-within-a-film scene of Brian DePalma’s Blow Out), but also the gendered violence of intrusion made perverse or pathological (Bates is dressed as his mother as he kills). Nowhere is this more obvious than in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, where Shelley Duval, unable to escape out of the bathroom, screams in horror as Jack Nicholson axes through the door. There is no transgression of gender boundaries here, just the dread of ubiquitous male access.

This, in a way, has been the story of shame this essay has attempted to convey. There is nothing inherently shameful about the bathroom; it is instead constructed as such in its physical, discursive, and affective architecture. To view HB-2 through the lens of The Shining rather than Psycho, is to espy a panoptic violence that conjures shame and self-doubt towards its own ends. We should, therefore, combat those real-world bathroom injustices precisely because it is a site of violence, not from trans people, but against them.

Laurent Berlant and Michael Warner open their 1998 essay “Sex in Public” with a section entitled There is Nothing More Public Than Privacy, an apt introduction to the social imperialism of heteronormativity. In charting an alternative, they argue that queer worlds constitute “a space of entrances, exits, unsystematized lines of acquaintance, projected horizons, typifying examples, alternate routes, blockages, incommensurate geographies.” To combat shame, we need to heed their advice, reclaiming the pleasures of being through alternative bathroom architectures; through queer geographies that do not limit, but liberate.

Stephen is a PhD candidate in American Studies at Rutgers University-Newark where he advocates for ethics and ontology beyond the human through analyses of media, science, and culture. He can be found on Twitter @mcnultyenator

Image courtesy of Salon

Comments 1

Bathroom Affects: Trans Rights and the Spectacle of Shame | Stephen Paul McNulty — October 15, 2016

[…] The original article can be found @Cyborgology […]