Despite increasing global attention and action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, climate change has become a contested political issue in the U.S. While Donald Trump has referred to climate change as a hoax, indigenous and environmental activists have mobilized to stop pipelines like Keystone XL and Dakota Access. Yet, why has climate change become politicized and how has the issue shaped the 2016 presidential election?

In this roundtable, we ask three leading scholars about the political and social dynamics of climate change and what implications the election will have on climate change policies. We examine how climate change can exacerbate social inequalities as well as generate social movements for environmental justice.

What implications could the election have on climate change policy?

Timmons Roberts: The stakes are high, as the outcome of the presidential election will have immense ramifications for the future of U.S. and international actions on climate change. Donald Trump has appointed Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute to be his climate and environment transition team leader, and Ebell has been a critic of climate change science and a very effective leader in the denialist movement. This appointment signals that Trump would decimate all climate efforts by the U.S. and undermine global agreements on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Riley Dunlap: The consequences of the current national election are enormous for climate change policy. Trump has promised to renege on the U.S.’s commitment to the recent Paris Climate Accord, and congressional Republicans have done everything they can to block implementation of Obama’s programs to meet commitments of the accord. In contrast, I think that a Clinton administration will follow Obama’s path, and should it have a Democratic majority in the Senate, commit the U.S. to international climate treaties requiring ratification. Thus, this election poses the starkest choice ever for climate change policies in our history. This led me and my colleagues to conclude our recent article on partisan polarization on climate change by saying, “Whether, and how, individual Americans vote this November may well be the most consequential climate-related decision most of them will have ever taken.”Eric Bonds: While Clinton on her own might not be a champion for climate change action if elected, her administration would give the climate justice movement an opportunity to develop and push for substantive change. This would certainly not be the case if Trump was elected. He would likely not be moved by climate advocacy, even if the climate movement was able to increase in size and amplify its voice.

What’s more, Trump’s emphasis on “law and order” echoes Richard Nixon’s platform when he was a presidential candidate in 1968. One way the Nixon Administration implemented “law and order” was through efforts to break up and quash the highly developed and effective social movements of that era. If Trump is elected, “law and order” might similarly be translated into attempts to intimidate those who voice dissent in general, along with direct attempts to suppress activism in the climate justice movement and the other important movements of our time, like Black Lives Matter and movements for gender equality and immigrant rights.

To what extent has climate change become an important and divisive issue in the presidential election?

Dunlap: Human-caused climate change has not become an important and salient issue in the presidential election, even though Hilary Clinton has taken a pretty strong proactive position while Donald Trump has basically denied its reality. Still, while the views of the two candidates, and the positions of the Democratic and Republican party platforms, are almost diametrically opposed on climate change, it is not close to being a top-tier issue. Climate change was barely mentioned by the moderators and candidates in the debates, and the media paid little attention to it.

My assessment is that with issues like economic problems, immigration, and terrorism being so salient, Clinton is not too keen on raising an issue that can be easily turned against her in fossil-fuel producing regions, especially coal-mining areas like southern Ohio. Republicans have already painted Democrats as waging a “war on coal,” so I think Clinton and many other Democrats feel the need to be cautious when talking about climate change. Especially in this election, slogans seem to trump (pun intended) serious discussion of policy issues, such as the need to transition to clean energy.

Roberts: The two candidates are very divided on climate change. Donald Trump is proclaiming how coal can save our economy and be made “clean.” Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, continues to describe a big push on solar energy, but there is a lack of salience with the public on climate change compared to her other core issues.

Bonds: Sociologist Kari Norgaard, in her book Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, gives us the wonderful distinction between explicit climate denial—in which individuals actively dispute its scientific basis—compared to implicit denial, in which a person accepts the realities of climate change but goes on living as if this was not so. It seems to me that this presidential election shows how these forms of climate denial can co-exist and reinforce one another. The implicit climate denialism of major news-media personalities allows Donald Trump’s explicit denialism to go unchallenged. But even without being elevated as an important issue in this race, climate change is certainly as divisive as ever.What impact have the climate change and climate justice movements had on national politics?

Bonds: The climate justice movement certainly had an impact in national politics in terms of its opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline. But I think that the true impact of this movement is yet to be felt. Possibly more impactful than social movements and grassroots pressure on recent climate policies are the numerous economic and national security policy experts who are aware that climate change poses tremendous challenges to society. I think these concerns motivated the Obama Administration’s climate policies in the past few years. But it’s important to stress that pushing beyond these reforms to really tackle the issue of climate change will require a very powerful social movement, which is yet to fully develop.

Roberts: I believe that the People’s Climate March in 2014 was important to show a new level of the scale of grassroots and popular mobilization on climate change. The climate justice movement has also had very strong local effects, especially in opposing pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure. These efforts are adding up to have a national impact on the direction the Obama Administration has taken on climate. More mainstream and faith-based efforts like Interfaith Power and Light, that are working between faith communities to build on Pope Francis’ encyclical on climate change, have also had an impact in raising awareness and political pressure. Still, fossil fuel extraction, like fracking, continues with devastating impacts on communities and the environment that will exacerbate environmental injustices.

Dunlap: In my opinion, neither climate change nor the climate justice movement has had a major impact on the current election, despite the efforts of climate activists like Bill McKibben to make climate change more politically salient. The climate justice movement might be able to mobilize at least a significant segment of the public — especially Millennials — concerned about climate change, but this is not certain and the impact on the election remains to be seen.

What accounts for climate change denial in the U.S.? Why do you think denial is particularly common in the U.S.?

Dunlap: I think the key is the dominance of the fossil fuels industry and prominence of neo-liberalism. My research, along with other sociologists such as Jeremiah Bohr, Robert Brulle, Justin Farrell and Aaron McCright, has shown that fossil fuel corporations like Exxon Mobil were early funders of denial, and they were quickly joined by conservative think tanks such as The Marshall Institute (check out an overview of the research). Fossil fuels corporations have a material interest in denying the significance of human-caused climate change, and their opposition to reducing carbon emissions is aided by modern society’s extreme reliance on cheap energy. The conservative movement, with its neo-liberal ideology opposing governmental regulations, views efforts to deal with climate change as posing enormous threats to the free-market economy. A major accomplishment of what we term the “denial machine” in the U.S. is turning “global warming” into a core element of conservative ideology, joining God, guns, gays, abortion, taxes and immigration. The result is that the Republican Party has become a key actor in climate change denial, with the GOP Congress in particular attacking climate science and doing its best to block Obama’s actions. Denial was first planted in the U.S., but quickly diffused (with the help of key American actors) to Australia, Canada and the UK, and to a lesser degree several other nations.

Bonds: There are a number of factors that contribute to comparatively high rates of climate change denial in the U.S. Important research contributions from Riley Dunlap, Aaron McCright, Robert Brulle, and many other scholars show that denial comes from somewhere, and that some groups are much more receptive to climate denialism than others, such as political conservatives. Individuals and corporations that are heavily invested in fossil fuels have mobilized extensive resources in order to develop and promote climate denialism. Their work is bolstered by very wealthy conservatives who are ideologically opposed to environmental regulations and the pro-active role of government. In sum, the stark political and economic inequalities in U.S. society are very conducive to climate denialism.

Roberts: The climate denial movement, which was devised in the late 1990s by a group organized by the American Petroleum Institute, has been very effective at delaying policies and regulation directed at climate change and reducing fossil fuel emissions. Corporations and industry groups have focused on the U.S. because of the access lobbyists have to the legislative processes and the possibility of unfettered campaign contributions, especially after Citizens United that enabled anonymous political spending.

How will action or inaction on climate change impact different communities? Will it contribute to inequalities?

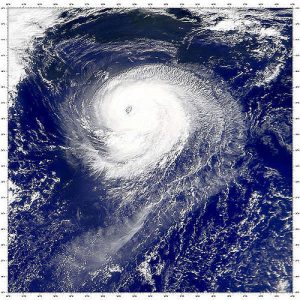

Dunlap: There’s no question that climate change will have differential and inequitable impacts on different populations, both nationally and especially internationally. We know that people living in vulnerable areas of the world (Bangladesh being a prime example with its immense amount of territory susceptible to rising sea levels) will suffer immensely, but the same dynamics operate within the U.S. Americans living in vulnerable areas, near sea coasts or low-lying areas in general that are susceptible to flooding (as we’ve seen from Hurricane Matthew in North Carolina) will be hit hard, along with poor people living in “heat islands” in urban areas. More generally, poorer regions and populations have less ability both to adapt to the multiple problems created by climate change as well as to mitigate their losses. One might say that, unless we change course in many ways, climate change will provoke greater degrees of environmental injustice than we’ve ever witnessed—and clearly we have witnessed many horrifying ones such as the on-going water crisis in Flint, Michigan.Bonds: Failure to transition our society away from fossil-fuel dependency will create terrible harm in the world as sea levels rise and as the climate takes up more energy and becomes more volatile. As Timmons Roberts and others have so convincingly argued, climate impacts will, no doubt, harm those individuals who contributed least to the crisis and who have the fewest resources to adapt. The major fossil fuel companies that fight carbon emission regulations and spend millions of dollars lobbying to thwart climate legislation, are all actively working to create conditions that will ultimately cause vast harm through climate change impacts. I think it is important for society to recognize that even if such outcomes are not intentional, they are predictable and avoidable.

Roberts: An all-out push for renewables and energy efficiency can be done with equity and justice, or it can be done in ways that reproduce inequalities and injustices. It all depends on how the transition from fossil fuels is done. As advocate and scholar Michael Dorsey says, if the approach to cleaner energy focuses on solar panels charging Teslas in McMansion driveways with poor working conditions for people making the products and disregard for the devastating impacts on communities where the materials are extracted, then creating a renewable energy economy will sharply contribute to inequalities. The poor could be left paying the maintenance costs of the huge electrical grid and paying higher rates due to increased costs of electricity generated from renewable sources, while the upper classes could have their electricity bills slashed by affording the latest technologies and efficiency upgrades. In our system, these are the business-as-usual outcomes we should expect. But there is an alternative. Approaches like community solar projects and weatherizing low-income housing, along with protections for workers in the green economy, could make a significant difference on how energy is produced and work to reduce social inequality.

Comments 1

Bob Williams — November 4, 2016

Do you remember how the six bilionaires who constitute U.S. mass media used to ignore Green Party Presidential candidate Jill Stein and Libertarian Party Presidential Gary Johnson? Jill Stein's idea of a Green New Deal, a $15/hour minimum wage, Medicare for All and combating systemic racism suffered a 'news-out' six months ago, but not in this last week before the November 2016 elections. Now voters are hearing about Jill Stein or Gary Johnson via social media. Greens and Libertarians are on the rise!