Hello friends of TSP,

This past Friday marked The Society Pages’ 5th anniversary, and we celebrated by eating cake with our awesome grad board. As we start a new semester and a new year, we wanted to give you, our friends, followers, and contributors, some highlights from the past year and some updates on what’s to come in the year ahead.

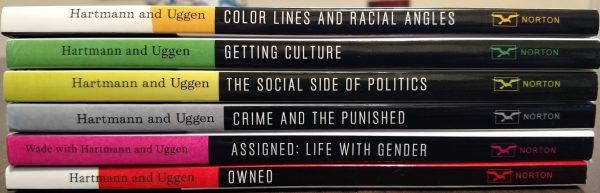

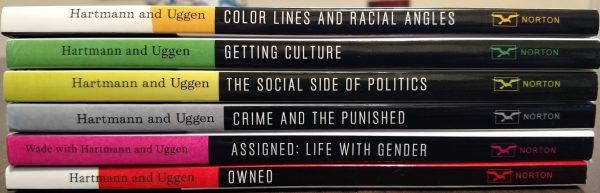

Looking back, 2016 was a big year for us here in Minnesota at TSP “world headquarters.” We produced 34 Discoveries (accessible summaries of new and notable research from sociology journals), 56 There’s Research on That! pieces (synthetic reviews of new and classic literature on a given topic), 8 Office Hours podcasts and 6 Give Methods a Chance podcasts, 67 Clippings (nods to sociology and sociologists in the news), and 5 original features. We also published Assigned: Life with Gender, a compendium of 29 essays guest edited by Lisa Wade, and now have a new volume, Give Methods a Chance, by TSP alums Sarah Lageson and Kyle Green, in production with W.W. Norton & Company. And this isn’t even to mention our partner organizations and dedicated community of bloggers – including many of you! – all of whom have been more productive and engaging than ever.

TSP will continue to evolve and grow in 2017. For one thing, in the next few weeks we are going to launch a new partner page called Social Studies MN. Focused on the work of our fabulous colleagues here at Minnesota, this will be an experiment in interdisciplinarity for us, in drawing from all across the social sciences more intentionally and systematically. We are also hoping to begin working with another sociological association or two in developing sites that highlight state and regional issues and experts. These new initiatives will take the place of our partnerships with W.W. Norton and Scholars Strategy Network, which both draw to a close after five wonderful and rewarding years. We thank those folks for all of their support in building TSP, and we will continue to pursue collaborations with them, albeit in more occasional and targeted ways, in coming years.

With these changes also come some transitions on our editorial team. Letta Page, our longtime associate editor, will move into more of a special projects mode for TSP proper, with graduate student editors Jacqui Frost and Evan Stewart taking up her day-to-day duties. (Yes, it takes two to replace Letta, who will also continue as Senior Managing Editor at Contexts and thus will be working with us on Contexts.org). Please use our new TSP specific email address for all site and submission inquiries going forward – tsp@thesocietypages.org.

We are also considering a little fund raising campaign so that we can continue to support and grow the graduate, editorial, and technical staff who write, edit, illustrate, and wrangle on our behalf. We are in the early stages of planning the campaign, but stay tuned in the coming months for details on how you can help. If you have any ideas, please do pass those along – again, at tsp@thesocietypages.org.

In conclusion, let us once again express our sincerest appreciation for your readership and particularly to those of you who have used The Society Pages’ freely accessible content in your classrooms, to those who write on our community page blogs, and to those who have championed us through our first five years and first seven books. We cannot thank you enough, and hope that we continue to enjoy your contributions and support in the months and years to come.