What works

This is a quiet story, the kind of thing that may or may not be picked up by a major national newspaper like the New York Times. Rural America is often used as a political flag to wave by politicians, but there is not often too much coverage of day-to-day life. The 2010 Census clearly shows,

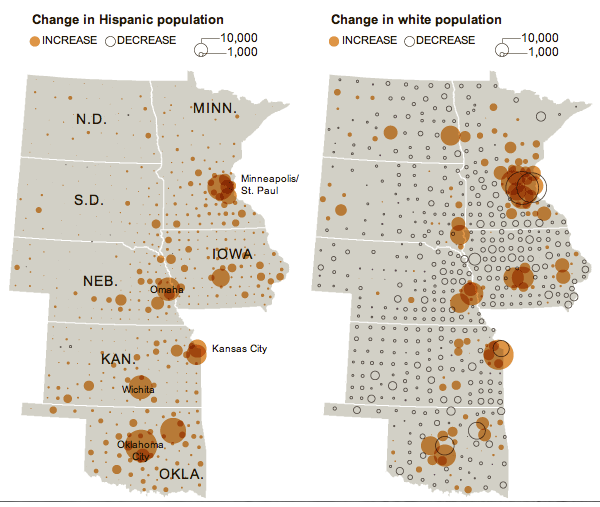

The Hispanic population in the seven Great Plains states shown below has increased 75 percent, while the overall population has increased just 7 percent.

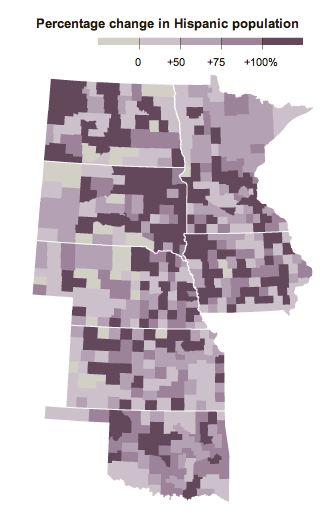

What is equally odd is that this story is running two graphics – the set of maps above and the one below – that more or less depict the same thing. I salivate over things like this because it gives me a chance to compare two different graphical interpretations of the same dataset.

The two maps above includes a depiction of the change in the white population as a piece of contextual information to help explain where populations are growing or shrinking overall. These two maps show that 1) in many cases, cities/towns that have experienced a growth in their hispanic populations also received increases in their white populations (hence, there was overall population growth) but that 2) there are some smaller areas that are experiencing growth in the Hispanic populations and declines in the white populations.

The second map shows only the growth in the Hispanic population without providing context about which cities are also experiencing growth in the white population. Looking at the purple map below, it’s hard to tell where cities are growing overall and where they are only seeing increases in the Hispanic population which is a fairly important piece of information.

What needs work

For the side-by-side maps, the empty and colored circles work well in the rural areas but get confusing in the metropolitan areas. For instance, look at Minneapolis/St. Paul. Are the two central city counties – Hennepin and Ramsey – losing white populations to the suburbs? That is kind of what it looks like but the graphic is not clear enough to show that level of detail. But at least the two orange maps allow me to ask this question. The purple map is too general to even open up that line of critical analysis.

This next point is not a critique of the graphics, but a direction for new research. The graphics suggest, and the accompanying article affirms, that Hispanic newcomers are more likely to move into rural areas than are white people. Why is that? Is it easier to create a sense of community in a smaller area, something that newcomers to the area appreciate? If that is part of the reason new people might choose smaller communities over larger ones, for how many years can we expect the newcomers to stay in rural America? Will they start to move into metro areas over time for the same reason that their white colleagues do?

Are there any other minority groups moving into (or staying in) rural America? Here I am thinking about American black populations in southern states like Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Are those groups more likely to stay in rural places than their white neighbors? For that matter, what about white populations living in rural Appalachia. Are they staying put or are they moving into cities like Memphis, Nashville, and Lexington?

How do things like educational attainment and income levels work their way into the geographies of urban migration?

References

Queens College Department of Sociology. (13 November 2011) Changing Face of the Rural Plains [information map graphics] Queens College: New York.

Sulzberger, A.G. (13 November 2011) Hispanics Reviving Faded Towns on the Plains New York Times: New York.