What works

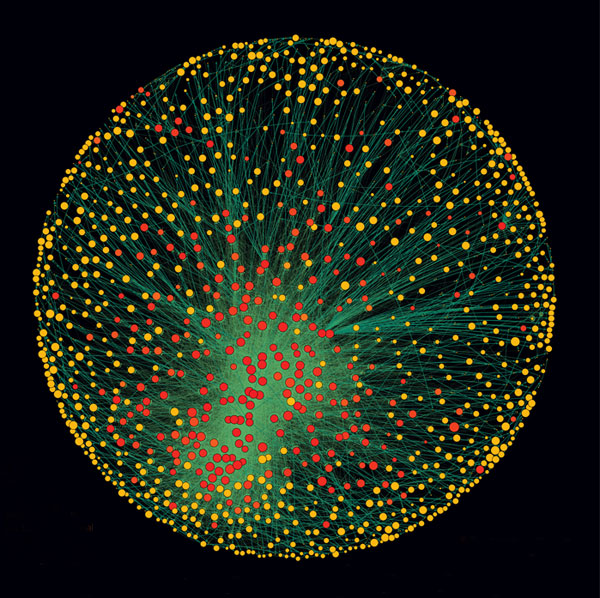

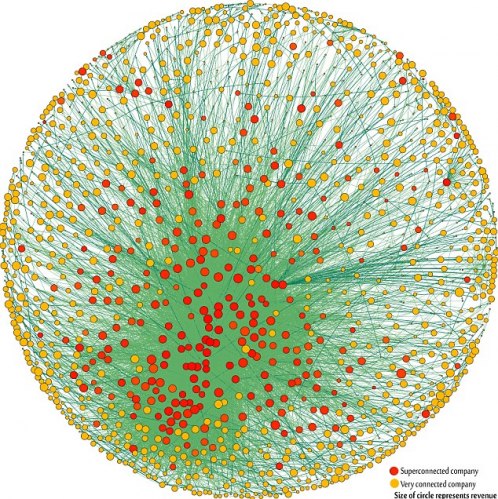

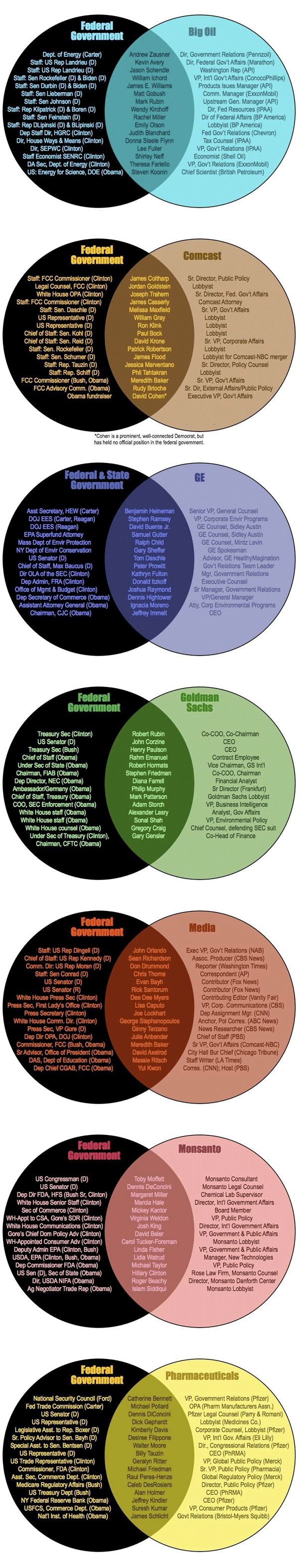

There is a lot of information here, that’s one of the best things about these Venn diagrams. People often stick a single word or a phrase in one circle, another in the next, and that’s it. But this graphic proves Venn diagrams can help organize much more detailed, drilled-down information fairly well.

What needs work

For the sake of legibility and small font sizes, I probably would have made one of the circles white instead of black, then left the colored one a color, and had the middle oval shape have a much lighter background. That might have helped make some of the text easier to read. In particular, I think it’s important to read the names themselves, so I would have worked to make sure they stood out.

I might have snugged the titles up to the curve. Their spacing is a little haphazard. Clearly, in a circular format, one cannot use a vertical margin line, but then that leaves a question about whether to mirror the shape of the circles on the outside or the ovaloid shape on the inside. I would have tried it both ways and then picked one. Not sure what happened here.

References

Herman, Stephanie. (2011) Venn diagram of Corporate Cronyism in America on geke.us