The election results are more or less in, along with a slew of disinformation about alleged voter fraud. You’ve probably head of #StoptheSteal, a viral-hashtag linked to groups claiming that the election results are inaccurate or illegitimate due to voter fraud. We at TheSocietyPages have published multiple articles and posts pointing to social science research demonstrating that voter fraud is not a big problem in the USA. Following the events of the last few weeks, we decided to provide you with an updated refresher of work in this area. It documents that voter fraud is virtually non-existent, and that if there are problems related to voting and voters in the USA, they have more to do with suppression and disenfranchisement.

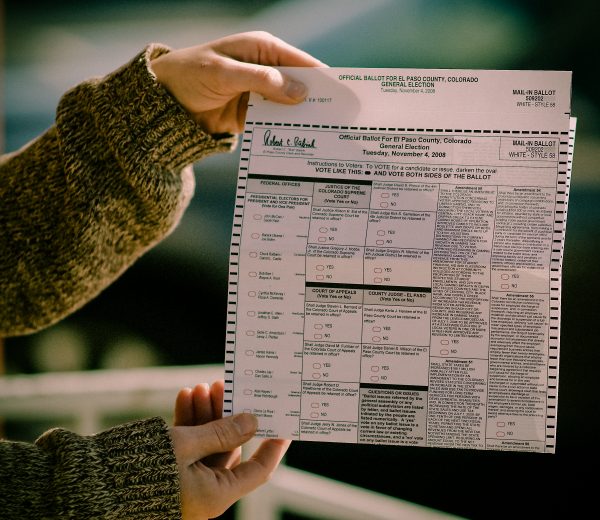

Across a variety of social science fields, data and research in the last decade shows that voter fraud is extremely rare in the USA. Some scholars estimate the level to be less than one-thousandth of one percent of all votes (i.e less than 0.001%), and that number is actually considered high by other scholars! Furthermore, of the few instances that could qualify as “voter fraud,” most involve issues of individual registration or ballot damage. There is no evidence of systemic, malicious attempts to subvert the results of the election. Indeed, the existing system of voter registration, as well as processing, counting, and sorting ballots, has been validated by extensive quality-control checks and fraud-prevention procedures. It will be a while before social scientists publish research about the 2020 election, but this author is willing to bet that findings will continue to illustrate a lack of voter fraud in the USA. Remember that the Federal Elections Commission has already stated that the 2020 election was one of the safest, most-secure elections in recent history.

- Sharad Goel, Marc Meredith, Michael Morse, and David Rothschild. 2020. One person, one vote: Estimating the prevalence of double voting in US presidential elections. American Political Science Review 114(2): 456-469

- Loraine C Minnite. 2010. The Myth of Voter Fraud. Cornell University Press.

- Pipa Norris, Sarah Cameron, and Thomas Wynter. 2018. Electoral Integrity in America: Securing Democracy. Oxford University Press.

- David Cottrell, Michael C. Herron, and Sean J Westwood. 2018. An exploration of Donald Trump’s allegations of massive voter fraud in the 2016 General Election. Electoral Studies 51:123-142

- Mirya Holman and J. Celeste Lay. 2018. They see dead people (voting): Correcting misperceptions about voter fraud in the 2016 US presidential election. Journal of Political Marketing 18(1-2): 31-68

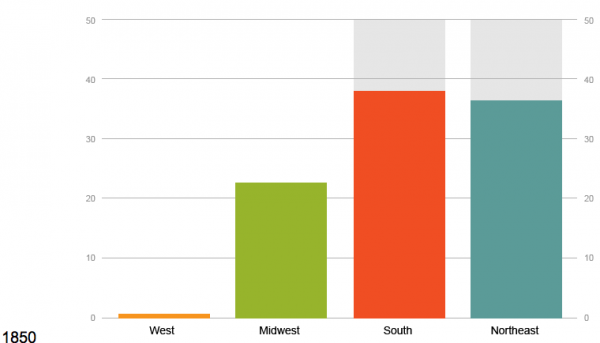

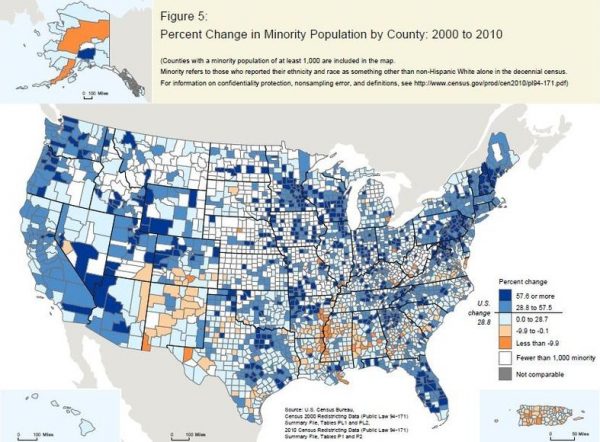

There is a real voting-related issue in the USA that goes unnoticed: voter disenfranchisement and voter suppression. In the past decade, the right to vote has come under attack in ways that are both typical and novel. For example, in many states people convicted of a felony lose their right to vote, even after their prison sentence is completed. This is a long-standing legal norm, but in recent decades, the population of incarcerated Americans has skyrocketed within a criminal justice system already rife with racial inequalities. Today, millions of Americans have been effectively barred from democratic participation, and a disproportionate number are Black, Hispanic, or Native-American.

- Chris Uggen., Ryan P. Larson, Sarah Shannon, and Arleth Pulido-Nava. 2020. “Locked Out 2020: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction.” via The Sentencing Project

- Hadar Aviram, Allyson Bragg, and Chelsea Lewis 2017. “Felon disenfranchisement.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 13: 295-311.

- Victoria Shineman. 2020. “Restoring voting rights: evidence that reversing felony disenfranchisement increases political efficacy.” Policy Studies 41(2-3): 131-150

Relatedly, voter suppression has grown throughf stricter ID laws, de-registration of voters, and other bureaucratic obstacles that make it harder for people to vote, even people who have voted in many elections beforehand. As the research below shows, voter suppression works in ways that skew the American electorate on racial and partisan lines, meaning the votes being cast are not truly representative of the American population.

- Matt A. Barreto, Stephen Nuño, Gabriel R. Sanchez, and Hannah L. Walker. 2019. The Racial Implications of Voter Identification Laws in America. American Politics Research. 47(2) 238–249

- John V Kane. 2017. Why Can’t We Agree on ID? Partisanship, Perceptions of Fraud, and Public Support for Voter Identification Laws. Public Opinion Quarterly 81(4): 943–955

- Lylia Hardy. 2020. Voter Suppression Post-Shelby: Impacts and Issues of Voter Purge and Voter ID Laws. Mercer Law Review 20(10): 857-878

- Brad Epperly, Christopher Witko, Ryan Strickler and Paul White. 2020. Rule by violence, rule by law: Lynching, Jim Crow, and the continuing evolution of voter suppression in the US.Perspectives on Politics 18(3): 756-769

- Zoltan Hanjal,John Kuk, and Nazita Lajevardi. 2018. We all agree: Strict voter ID laws disproportionately burden minorities. Journal of Politics. 80(3): 1052-1059

Ideally, our society would take the energy spurred by the fantastical, imaginary arguments of the #StoptheSteal campaign and instead address the very real issues that compromise our democracy, taint the voting process, and unduly impact election outcomes. The research cited above suggests that removing obstacles to voting would increase individual political participation and general voter turnout; if we’re in pursuit of an ideal democracy, shouldn’t such issues be at the forefront?