Diversity is heralded by institutions as one indicator of their excellence. In a recent ranking of Ivy League colleges by The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education, Columbia University rose to the top, in part because it ranked high on “environment” — measured by the racial and ethnic diversity of faculty and students as well as the number of international students enrolled. Recognizing the value of diversity, Yale and Brown announced ambitious plans to increase faculty and student diversity, with commitments from their respective administrations of $50 and $100 million. While diversity is a core component of institutional excellence, promoting diversity, seeing it, and even the mere mention of it can generate a backlash — or what CNN commentator Van Jones aptly dubbed a “whitelash” to characterize the support that Trump received from White voters to propel him to the presidency.

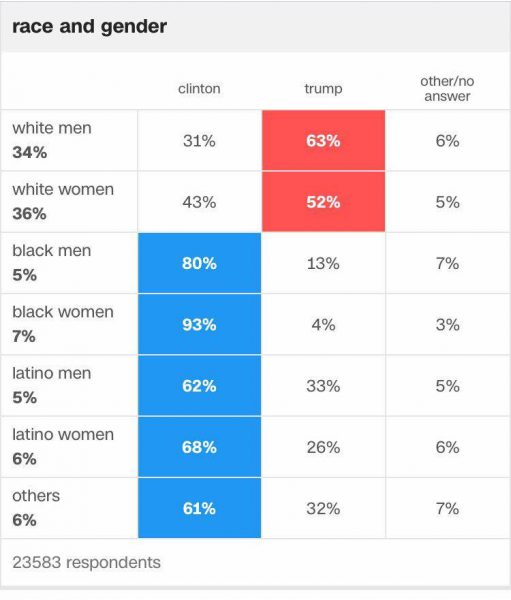

Exit polls show that the majority of Trump’s supporters were White, and that the majority of Whites — both men and women and across all income brackets — voted for Trump. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of White men voted for Trump, and among those without a college degree, support rose to 72 percent. Race trumped gender for White women: Trump garnered 52% of their votes, and among White women without a college degree, support increased to 62 percent. By stark contrast, only 17% of Asian and 18% of Latino voters chose Trump, and among Black voters, a mere 8 percent did so.

The racial fault lines in the polls reflect the divisions that Trump decisively carved throughout his campaign, and cemented even more deeply since his election. During an interview on 60 Minutes, President-elect Trump declared that he would deport two to three million undocumented immigrants “immediately” upon taking office, and confirmed that he plans to move forward with his plan to “build a wall” between the United States and Mexico. In addition, Trump’s policy advisers are discussing a proposal that would force immigrants from Muslim countries to register on a database. And Steve Bannon—Donald Trump’s chief strategist— expressed concern that “two-thirds or three-quarters of the CEOs in Silicon Valley are from South Asia or from Asia.”

With each assault, Trump and his advisors are attacking diversity, and in doing so, they lead White Americans to associate diversity with threat.

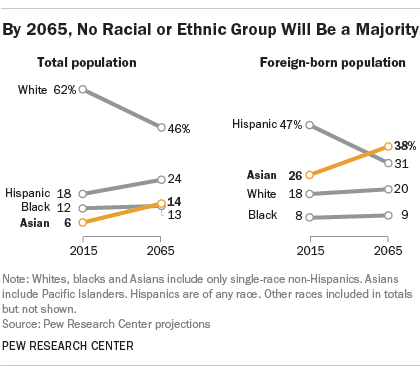

To understand the link between diversity and threat, consider the research of psychologists Maureen Craig and Jennifer Richeson who find that politically unaffiliated White Americans reacted to learning about California’s rapidly changing racial demography by leaning more toward the Republican party. Moreover, after learning that the U.S. Census Bureau projects that racial minority groups will make up a majority of the U.S. population in 2042, Whites are more likely to endorse politically conservative policies. The driving force underlying these effects is group-status threat — the threat or fear that Whites will lose their privilege and dominant position in America’s racial hierarchy.

Research by sociologist Frank Samson also finds evidence of group-status threat among White Californians when it comes to admissions to elite universities. When evaluating Asian American applicants, Whites prefer to decrease the weight of grade point averages (GPAs), but when considering Black applicants, Whites choose to increase their importance. In each case, Whites weigh GPAs differently depending on the racial group in question, and in the direction that benefits them, guards their privilege, and minimizes group-status threat.

Research by sociologist Frank Samson also finds evidence of group-status threat among White Californians when it comes to admissions to elite universities. When evaluating Asian American applicants, Whites prefer to decrease the weight of grade point averages (GPAs), but when considering Black applicants, Whites choose to increase their importance. In each case, Whites weigh GPAs differently depending on the racial group in question, and in the direction that benefits them, guards their privilege, and minimizes group-status threat.

Sociologist Natasha Warikoo provides yet another lens through which to understand the relationship between diversity and threat. Based on interviews with White students in elite universities in the United States and Britain, she finds that while they support affirmative action programs because they increase diversity on their campuses — a collective good from which all students benefit — they withdraw support when they feel that minority groups receive benefits that are denied to them. For example, the existence of a Black, Latino, and Asian Students’ Associations but not a White Students’ Association violates the equal treatment of all students, in their view, and even ignites charges of “reverse discrimination.”

In sum, this research shows that the country’s changing demographic diversity can lead White Americans to endorse more conservative policies, lean more Republican, shift their evaluation of merit, and believe that they are now the victims of racial discrimination. Critical to add is that White Americans need not hate or be consciously biased against African Americans, Latinos, Asians, immigrants, or Muslims to feel threatened by their growing presence.

The lesson here is that demography is not destiny, as we learned from the rise of Trump. But the mere threat of it has generated a “whitelash” that propelled Trump into the nation’s highest office. Understanding group-status threat and its consequences is the first step to addressing them, which makes the role of universities — and their steadfast commitment to diversity and equality — a critical partner in this endeavor.

Recommended Readings:

Sigal Alon and Marta Tienda. 2007. “Diversity, Opportunity, and the Shifting Meritocracy in Higher Education.” American Sociological Review 72 (4): 487-511.

Emilio J. Castilla and Stephen Benard. 2010. “The Paradox of Meritocracy in Organizations.” Administrative Science Quarterly 55: 543–576

Maureen A. Craig and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2014. “On the Precipice of a ‘Majority-Minority’ America: Perceived Status Threat From the Racial Demographic Shift Affects White Americans’ Political Ideology.” Psychological Science 25 (6): 1189- 1197.

Frank L. Samson. 2013. “Multiple Group Threat and Malleable White Attitudes towards Academic Merit.” Du Bois Review 10 (1): 233–260.

Natasha K. Warikoo. 2016. The Diversity Bargain: And Other Dilemmas of Race, Admissions, and Meritocracy at Elite Universities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Comments 3

Rick Herbel — November 18, 2016

If you look at historical voting by race, not much of a change. In fact, Looks like trump took away from the democratic race support. The only question I have is the data accurate?

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/09/behind-trumps-victory-divisions-by-race-gender-education/

Daniel L. Carlson — November 19, 2016

Republicans always win the majority of the white vote and Trump won a smaller percent of the white vote than Romney in 2012 -- 58% to 59%(See CNN exit polls for 2016 and 2012). This is because the wave of less than college educated whites to Trump was offset by a shift of college educated whites toward Clinton. Thus, for people to continually call this a "whitelash", though a convenient and seemingly truthful narrative, is misleading. The majority of whites vote Republican and have for decades. Moreover, the racism and racial threat was always there and was always a major factor in how many whites voted. Its just that in the past it was conveyed with dog whistles and innuendos, now it is shouted with a bullhorn and made central to the party platform. If anything the lesson learned is that for all the whites that Trumps messaging turned on, he turned off just as many.

Mary Kritz — November 22, 2016

How should we interpret the race and gender statistics in the chart given that the percentages of black men and women and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic men and women, who voted for Clinton were larger or equivalent to the percentages of whites who voted for Trump? Does this reflect fear of whites, fear of change, or fear of what?