In February of 1926, Carter G. Woodson helped establish “Negro History Week” to educate teachers, students, and community members about the accomplishments and experiences of Blacks in the United States. A native of Virginia, and the son of formerly enslaved parents, Woodson earned a PhD in history from Harvard University, and dedicated much of his life to writing and teaching about information largely omitted from textbooks and other historical accounts. Although Woodson died in 1950, his legacy continues, as “Negro History Week” eventually became “Black History Month” in 1976.

Nearly a century later, Black History is still at risk of erasure, especially in (once) geographically isolated areas, like Appalachia. The standard narrative that Scots-Irish “settled” Appalachia starting in the 18th century hides the fact that there were often violent interactions between European immigrants and indigenous people in the region. Even in the 1960s when authors like Michael Harrington and Harry Caudill reported on Appalachian mountain folk, the people were depicted as Scots-Irish descendants, known for being poor, lazy, and backward, representations that are reinforced in contemporary accounts of the region, such as J. D. Vance’s wildly popular memoir Hillbilly Elegy.

Accounts like these offer stereotypical understandings of poor Appalachian whites, and at the same time, they ignore the presence and experiences of Blacks in the region. Work by social scientists William Turner and Edward Cabell, as well as “Affrilachia” poet Frank X. Walker, and historian Elizabeth Catte attempts to remedy this problem, but the dominant narrative of the region centers still on poor whites and their lives.

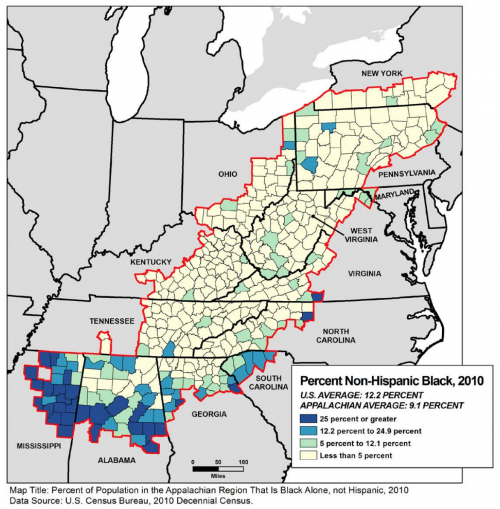

Work I have been doing documenting the life experiences of Leslie [“Les”] Whittington, a native of Western North Carolina and a descendent of a formerly enslaved people, has opened my eyes to a historical narrative I never fully knew. African Americans, for instance, accounted for approximately 10% of the Appalachian region’s population by 1860, and many were enslaved, including Les’ grandfather, John Myra Stepp. Yet, their stories are glaringly missing from the dominant narrative of the region.

So too are the stories of Blacks living in Appalachia today. Even though the number of African American residents has increased in some parts of Appalachia, while the white population has decreased, little is formally documented about their lives. That absence has led scholar William Turner, to refer to Blacks in Appalachia as a “racial minority within a cultural minority.” Not only does erasing African Americans from the past and present of Appalachia provide an inaccurate view of the region, but it also minimizes the suffering of poor Blacks, who relative to their white counterparts, are and have been the poorest of an impoverished population.

Woodson established “Negro History Week” to document and share the history of Blacks in the United States, recognizing that, “If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.” The history of African Americans in the Appalachian region is largely absent from the area’s official record, and without making it part of the dominant narrative, we risk losing that history.

Jacqueline Clark, PhD is a professor of sociology at Ripon College. Her teaching and research interests include social inequalities, the sociology of health and illness, and the sociology of jobs and work.

Comments 74

Les Whittington — February 20, 2019

Excellent, thanks for sharing, all need to know this history!

weed and feed — February 21, 2019

I'd like to find out more? I'd want to find out more details.

Mike Coggeshall — February 21, 2019

Here's more research on the topic:

https://www.uncpress.org/book/9781469640853/liberia-south-carolina/

buat toko — February 22, 2019

Thanks for sharing those pictures. btw., there is a software which can make them colored. it would be interesting to see their clothes, faces, streets and buildings..

Agus Young | Blogger | caramembuatwebsiteku.com

Brittany Lancaster — February 28, 2019

great content! Thanks, https://thesocietypages.orgthesocietypages.org

Matt — March 1, 2019

not exactly Appalachia, but to your point about black settlement in rural areas: https://www.limestonepostmagazine.com/lick-creek-settlement-holds-piece-of-black-history-indiana/

Mercella Fiddler — March 24, 2019

Whenever the term race is discussed on a sociological standpoint, I understand it to be dealing with a cohort of people constructed on shared physical or social qualities into categories generally viewed as distinct by society. Race has been a contentious topic in America due to the disproportionate advantage majority groups enjoy over minority groups over the years. The matter has become a more intense debate in the media today chiefly because of the “Black Life Matter Group” An international group of African-American campaigning against violence and systematic racism towards blacks. The Presidential campaign slogan “Make America Great Again” has also had some detrimental repercussion on the lives of black people”. It brought a refreshed hope into the minds of white American that making America great again will result in an America where the laws of Jim Crow can be reestablished and blacks can again be treated as one- fifth of the value of a white person. Thus, A discussion about race cannot be void of the subject of stereotype which lead to inferior or superior group identity. Another such issue that is deeply rooted into the discussion of race is ethnicity, which is the state of belonging to a particular social group that experience a common cultural tradition. Consequently, Race; stereotype and ethnicity are intertwined and interrelated in all aspects of human society.

In an article entitled Lil Wayne and colorblind Racism by Jeannette Wade, the writer discussed an interview between rapper Lil Wayne and ABC News' host Linsey Davis where the rapper was asked his views on Black Life Matter. The rapper replied unapologetically, “I don't feel connected to a damn thing that ain't got nothin' to do with me." Lil Wayne’s response can be associated with two of the six ways Sociologist Edwardo Bonilla-Silva explained racism lives on through colorblind rhetoric.

“complete inclusion, or the notion that all citizens belong to one race. This allows us to take the focus off specific race groups who are systematically disadvantaged.” (Edwardo Bonilla- Silva)

Lil Wayne belief that he is loved by all races as an African American rap artist gives him complete inclusion into mainstream society. With such honor he chose to turn a blind eye on the major social problems faced by minority groups, the group from which his ancestors are aligned. He cannot relate to the experience of being racially profiled or stereotyped. On that account, he has become numbed to the numerous racial murders by White law enforcement officers targeting African American youths. These officers refuse to follow protocol because they are wired with the stereotypical views of minority groups as being criminal and underserving of life, especially since blacks are no longer slaves and deny “ Make America Great Again”. As such they allow their personal beliefs and the grassroot belief of white America to guide their judgement when dealing with minority groups.

“Avoiding racist language, which implies that racism is only perpetuated via the use of slurs.” (Edwardo Bonilla-Silva)

The response calls into question whether racism has a significant impact on where an individual fall on the social ladder despite race and ethnic background. I use social ladder loosely to incorporate social stratification, Notwithstanding, that blacks are always at the bottom of that ladder in American history, but with money and fame an individual may be able to interact on a level playing field with their white counterparts. Subsequently, I deduced that material possession bestow certain privileges on Lil Wayne, individuals with the lack there of do not enjoy. However, if the definition of the terms race, ethnicity and stereotype holds true then one can not deny Lil Wayne has gone colorblind believing that racism is defined based on material possession.

Food for thought, Would a troubled Wayne Michael Carter, Jr. an African - American teenager from New Orleans responded in like manner to the question posed twenty years ago owing that he possess all the physical characteristics used to define African -American thugs?

Work Cited

King, A. Laura (2017) The Science of Psychology: An Appreciative View Myers David (2010) Psychology Ninth Edition. 455 - 464

Wade Jeanette Lil Wayne and Colorblind Racism, Race/Ethnicity/Theory April 12 2017 http://sociologyinfocus.com/2017/04/lil-wayne-colorblind-racism/ March 23, 2019

Diana Matthews — March 29, 2019

Very interesting article thanks for sharing this info. You are a really talented author and I suppose that you could help with admission essay to many students and also earn good money on it. If you are interesting contact the draftify.net or similar company they are always looking for cool writers like you.

Paul Martinez — May 15, 2019

If you are a student, you may know that time is the most valuable resource. Sometimes it's so difficult to deal with countless assignments. As I'm a student too I know it very well. Good, that I have found a place where I can buy dissertations online and save a lot of time and avoid stress and worries.

Amelia — December 13, 2019

I can't live outside of you

I'm one with you

Only time passes

I love you. Thank you

Hug me warmly

Whenever this love can live

Every time I love, I can live

emoji

CharlesAGood — March 3, 2021

Hello, I am writing an essay on Appalachia. And for that, I am gathering information online. I am glad I have found your post in which you have shared a hidden black history in Appalachia. I am also searching for a business plan for ecommerce online. I hope, I will find it soon.

AdelleHPenix — March 23, 2021

Hello, thanks for sharing this information with us. I was reading an article language learning books on http://www.omniglot.com/language/articles/languagelearningbooks.htm site and while reading, I have found your post. And after reading your post, I am thinking about writing an essay on hidden black history.

AdelleHPenix — March 23, 2021

Hello, thanks for sharing this information with us. I was reading an article language learning books on http://www.omniglot.com/language/articles/languagelearningbooks.htm site and while reading, I have found your post. And after reading your post, I am thinking about writing an essay on hidden black history

Klais Surik — September 23, 2021

In reality, if you need to develop applications, you should seek assistance from specialists. Because there are a lot of low-quality apps out there that are difficult to get rid of so you don't have to pay for advertising. As a result, I propose reading https://webspaceteam.com/web-development/ , which will help you better grasp the issues. I hope I was of assistance!

maiklsas hary — October 27, 2021

Thanks for sharing this amazing thing. Keep sharing more useful and visible stuff like this. Thanks !

among us

bettywnieves — April 14, 2022

find essay writing help

my arlo login — May 25, 2022

open up an internet browser and go to my.arlo.com login page. This is the welcome screen for your Arlo device. You need to enter the login information such as email address and password to sign in. To know in-depth details, just contact our technical experts on their toll-free number.

my arlo login — May 25, 2022

My arlo login page can be opened by using the web address my.arlo.com. Just enter this web address to access the ‘My Arlo login’ account. After signing in, you can connect Arlo base station to Arlo camera. If my.arlo.com is not responding, you can use the Arlo app for arlo login.

Jason Adams — May 27, 2022

While playing online casino games, the first step is to find a safe and secure casino. The security of your personal information is paramount. In addition to ensuring that your information is encrypted, check that the casino is a legitimate entity registered and regulated in your jurisdiction. If the casino does not have a trading license, avoid them. The best way to play online casino slots safely is to stick to reputable operators. There are many ways to choose a casino that offers reliable customer service read more about safe casino at wild.tornado.

otis — July 13, 2022

The Appalachian Mountains are a great place to learn about the history of black people in Appalachia. There were pokedle slaves in the mountains, and they fnaf could escape to the mountains to live freely. Many people came up from Africa during slavery times and settled in the Appalachian Mountains.

candy candy — October 2, 2022

The most well-known Appalachian tales from the late nineteenth century to the present have been straightforward accounts of white mountaineers. The first time I found out from basketball stars and read it I was very emotional.

Thorothy Yoatkin — October 13, 2022

When we think of sports, the majority of us immediately think of soccer. This is the most common sport in the whole world. Therefore, it would not be surprising if this is one of the most popular sports to https://gaminatorinsecret.com/en/ bet on. Nothing makes us happier than when our favorite club wins.

Thorothy Yoatkin — October 13, 2022

You might not see it coming, but tennis is one of the most popular sports that people bet on. The rise of live gaminator 3 betting makes tennis matches more fun more often because you get the chance to change strategies every minute or set.

Jeffery Riddle — February 20, 2023

This is such a simple idea, and yet I'm not sure why other browsers (especially Firefox) didn't add it. Just from reading the comments, it looks like a lot of people are fond of this dino game

ahmedo ony — May 31, 2023

i really enjoy reading content and learning new information, I think you should try it too fix oyun

oyun oyna — July 27, 2023

Thank you for a good article

oyun oyna — July 27, 2023

Thank you for a good article

oyun oyna — July 27, 2023

Thank you for a good article https://www.1001oyun.org/

Maria — September 8, 2023

Thanks for sharing this detail post about the Hidden Black History in Appalachia. They are amazing people with different innovative ideas that are hard to find in other ethnicities. I found that the house painters also think in the same way.

Jasmin Huels — November 13, 2023

Nice article! Have you explored the lesser-known Black history of the Appalachian region?

JIN69 — February 5, 2024

The best money-making JIN69.ink online game that everyone plays

Civaget — April 18, 2024

I've found some hidden gems through 오피사이트's business listings.

Civaget — April 21, 2024

Highly recommend 인천오피 for anyone in need of some self-care. The treatments are divine, and the ambiance is serene.

Civaget — April 21, 2024

Absolutely loved my experience at 오피타임. The spa facilities are pristine, and the massages are divine. Highly recommend to everyone!

Dom — April 22, 2024

The community on 마나토끼 is so welcoming and inclusive, making it easy to connect with other fans and share our love for webtoons.

Dom — April 22, 2024

Reading reviews on 오피가이드 feels like getting advice from friends. It's a community I trust.

Dom — April 22, 2024

Just joined opga and already feeling welcomed by the community. Excited to dive in!

Dom — April 23, 2024

Finding reliable travel tips has never been easier thanks to 여기여. It's my go-to platform for trip planning.

Dom — April 23, 2024

The community aspect of 주소야 sites adds value to the curated links.

Dom — April 23, 2024

The curated links on 주소월드 are top-notch. I always find quality information there.

Dom — April 23, 2024

링크모음 streamlines my internet experience. Love how easy it is to find what I need.

Dom — April 23, 2024

I've saved so much time thanks to 여기여. No more endless searching for quality links – it's all right here.

Dom — April 23, 2024

Discovering new interests through 주소야 sites' curated links.

아지툰 — April 28, 2024

아지툰's commitment to empowering creators ensures that aspiring writers have the resources and opportunities to succeed.

아지툰 — April 28, 2024

The addictive nature of 아지툰 keeps me coming back for more. I just can't get enough!

무료웹툰 — April 28, 2024

This 무료웹툰 platform has everything I need for hours of entertainment.

무료웹툰 — April 28, 2024

The search function on this 무료웹툰 platform is super handy. Makes finding new series a breeze!

여기여 — April 28, 2024

Love the user-friendly interface of 여기여. Makes exploring links enjoyable.

여기여 — April 28, 2024

The search function on 여기여 is impressively accurate. I can always count on finding exactly what I'm looking for.

대밤 — May 1, 2024

The variety of suggestions on 대밤 is impressive—it caters to all tastes.

Dom — May 1, 2024

I've discovered so many amazing spots through 오피의신. It's become an essential tool for planning outings.

밤떡 — May 1, 2024

I love how easy it is to navigate through the suggestions on 밤떡. It's user-friendly and intuitive.

밤의민족 — May 1, 2024

밤의민족 is my secret weapon for planning leisure activities. Love the diverse range of reviews and suggestions.

Dom — May 1, 2024

The 펀초 app is a must-have for anyone living in or visiting Busan. It's so useful!

Dom — May 1, 2024

부비 has helped me discover so many amazing businesses in Busan that I never would have found otherwise.

Dom — May 1, 2024

I appreciate the transparency of reviews on 오피쓰. It helps me make informed decisions when choosing leisure centers to visit.

Dom — May 1, 2024

I'm constantly amazed by the creativity of the 오피아트 community.

Dom — May 1, 2024

Love the sense of camaraderie on 헬로밤. Feels like a virtual family.

Dom — May 2, 2024

I highly recommend checking out 아이러브밤 for anyone looking to discover new businesses and connect with like-minded individuals.

Dom — May 4, 2024

As someone who enjoys exploring different genres, I appreciate the wide range of options available on 툰코.

sohbet — June 13, 2024

Hey, you used to write wonderful. Maybe you can write

hakan — June 13, 2024

Thak you sohbet

ugur — June 13, 2024

news bussinesses and connect with like-minded individuals... okey

geometry dash — June 14, 2024

In the early decades of the 20th Century, coal company agents recruited black labor from the South to work in the mines of Appalachia.

Shaun Woodward — June 14, 2024

Black history in Appalachia includes the contributions of Black soldiers in World War I, the migration of African Americans to the geometry dash region, and the book Unearthing New Histories of Black Appalachia.

러시아야동 — June 26, 2024

Explore the premier platform for accessing a variety of high-quality Western adult video services. We provide detailed reviews, current information, and exclusive access to the best sources for Western adult content. Our expert recommendations ensure you have a superior and secure viewing experience. Join us to discover the top services for diverse and premium Western adult videos online. 러시아야동

국산야동 — June 26, 2024

Discover the best platform for finding high-quality Korean adult video sites. We offer detailed reviews, up-to-date information, and exclusive access to trusted sources for Korean adult content. Our expert recommendations ensure you enjoy top-notch and secure viewing experiences. Join us to explore the finest sites for high-quality Korean adult videos online. 국산야동

애니야동 — June 26, 2024

Explore the premier platform for accessing high-quality and diverse adult animation content. We offer curated selections, updated releases, and exclusive access to top-tier sources for adult animated entertainment. Our expert curation ensures you enjoy premium and varied animation collections. Join us to indulge in the best of adult animated content online. 애니야동

오피사이트 — June 26, 2024

Discover the premier platform for the latest domain guides to companies offering passionate services in officetels. We offer comprehensive reviews, updated information, and exclusive access to the top officetel companion service directories. Our expert recommendations ensure you find reputable sources for indulging in passionate experiences. Join us to stay informed on the best officetel companion service destinations online. 오피사이트

조개모아 — July 4, 2024

Discover the ultimate platform for accessing high-quality adult videos anytime, anywhere. With our extensive library, you can enjoy diverse content ranging from sensual to explicit. Our user-friendly interface ensures seamless streaming on any device. Join us to explore the best of adult entertainment at your fingertips. 조개모아

국산야동 — July 4, 2024

Discover the best platform for finding high-quality Korean adult video sites. We offer detailed reviews, up-to-date information, and exclusive access to trusted sources for Korean adult content. Our expert recommendations ensure you enjoy top-notch and secure viewing experiences. Join us to explore the finest sites for high-quality Korean adult videos online. 국산야동

온라인바카라순위 — July 4, 2024

Discover the best online casino sites through our top-rated advertising platform. We feature comprehensive reviews, exclusive bonuses, and up-to-date promotions to enhance your gaming experience. Our trusted recommendations ensure you find secure and entertaining casinos. Join us to explore the finest online gambling destinations. 온라인바카라순위

evolution casino — July 4, 2024

Discover the premier platform for guiding users to Evolution Casinos. We offer comprehensive reviews, exclusive bonuses, and up-to-date information on the best Evolution Casino sites. Our expert recommendations ensure a safe and enjoyable gaming experience for all players. Join us to explore the top Evolution Casinos available online. evolution casino

사이트모음 — July 4, 2024

Discover the ultimate platform for the latest domain guides on adult content, webtoons, office sites, torrents, movies, TV shows, sports TV, safest betting sites, adult products, and overseas Korean sites. Our comprehensive site offers expert reviews, updated information, and exclusive access to the best resources across these categories. Stay informed with detailed analysis and the newest trends in the online world. Whether you're seeking entertainment, secure betting, or domain advice, our recommendations ensure you find the best sites available. Join us to access the most reliable and current domain guides online. 사이트모음