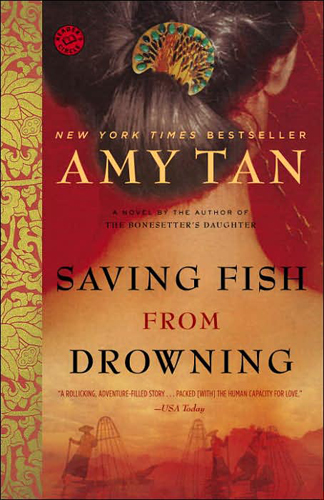

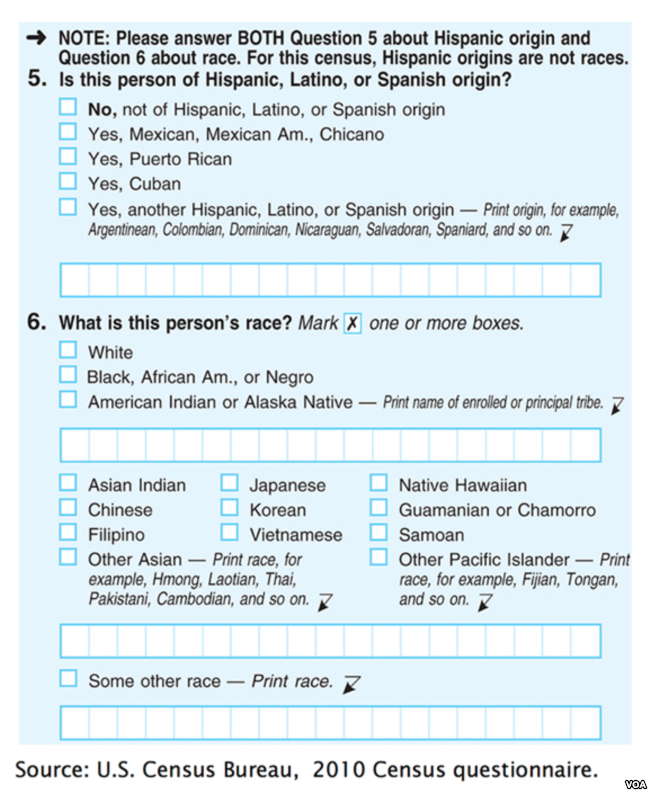

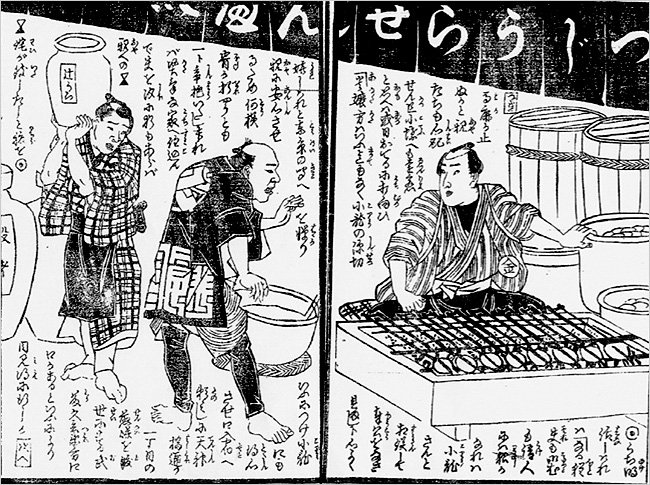

If you’re designing a cover for a book by a Chinese or Japanese writer, or with a Chinese or Japanese setting, it seems that there are some compulsory elements which must be included. For variety’s sake, there are four elements, but you MUST use at least one of them. Advanced designers, of course, may use two or more.

Element 1: Blossoms (preferably cherry, but anything red or pink will do)

Element 2: Fans (preferably held so as to partly obscure a woman’s face (or genitals), and if you can get blossoms on the fan, you get bonus points)

Element 3: Dragons (for use only on crime novels, or other exciting tales)

Element 4: Female Necks (preferably that of a geisha, but any female neck will do in a pinch)

For more on this trend, see this article from Hyphen Magazine, which features a brief interview with ace designer Henry Sene Yee. It was that article which also drew my attention to two covers featured above, those for On a Bed of Rice and The Street of a Thousand Blossoms.

(To be fair, I ought to note that several of these covers are actually very nice–it’s just that they lose rather a lot of their impact because of the familiarity of the elements used.)

James Morrison (jrsmorrison@yahoo.com.au) is a writer, editor and graphic designer who lives in Adelaide, Australia. He writes about book covers and book design at causticcovercritic.blogspot.com, and used to write about novellas at Book Slut. He blogs at Caustic Cover Critic. Thanks to Lisabee for the hat tip.