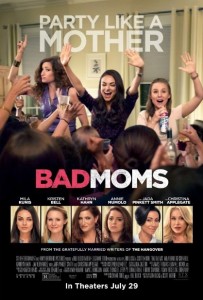

The recent movie “Bad Moms” calls to mind how motherhood is often depicted in extremes and through exaggerated metaphors of hovering helicopter PTA moms.

The recent movie “Bad Moms” calls to mind how motherhood is often depicted in extremes and through exaggerated metaphors of hovering helicopter PTA moms.

We three work closely on the topics of parenthood, education, and family in our careers, and we also go to movies together. Sometimes it’s hard for us to find the time to do this. We’d like to say that this is because we each spend oodles of time filling our children’s lunch boxes with organic foods grown in our gardens, but this would only be accurate if our children’s lunch ingredients included slugs.

Did you catch that? How we turned something good into something bad? Or was it the other way around? Is it good to fill lunches with hand-picked organic carrots from our back yards or is it good to embrace slugs and store-bought snack packs? Which is the better “mom achievement?”

This twisting of goodness into badness and badness into goodness for moms is precisely the premise of the movie “Bad Moms,” which we recently saw together on one of those “Girls Night Out Because They Deserve a Break” evenings (okay, that’s not how we think of our time together, but we know lots of people for whom this label hits pretty close to home, and this “self-care” framing matters, as discussed below).

The movie’s premise is as follows: high-heel-wearing-overworked-taken-for-granted mom Amy decides to stop doing the things she (along with the hyperbolic PTA bake-sale-policing ubermoms) defines as good momhood, and that are supposed to make her (and her kids) happy. No more making healthy organic lunches. No more doing her son’s (“I’m a slow learner”) school projects. No more succumbing to the pressure her daughter was placing on herself to achieve achieve achieve. No more enabling of her husband’s juvenile ways that make the audience astounded that he can keep any children alive until the end of the day (the presentation of incompetent dads and the complexity of fatherhood could fill another blog post, by the way).

She. Was. Done.

Amy meets up with new friend Carla – a single mom who works in a service industry job – to realize that kids are probably fine even if you don’t tend to them like a delicate flower in an organic garden (though Carla’s lower SES background is stereotyped in enough ways to fill yet another blog post, where we could discuss how the three of us can drop off an Arby’s bag for our kids’ lunches, but we’ll still have more cultural capital than parents in our town who work three jobs and don’t have a car). Add a third to the mix – Kiki, a stay-at-home meek-to-her-husband’s-demands mom of four – and the audience gets to hear the wishes of moms who just want to be in a small accident so they can be rewarded with hospitalization for a week with lots of peace and quiet and no responsibility. Hospitalization as a means to happiness.

At several points in our viewing, the three of us laughed out loud. At other points we turned to each other to whisper things like “I think this is a good kind of feminism,” or “This is not a good kind of feminism.” By the end of the movie, we observed that the feel-good part with swelling music and welling eyes was all about moms needing to relax about trying to achieve perfection. Stop doting. Stop helicoptering. Stop organic carroting. And stop all of this, by the way, because our kids are swimming in either: a) anxiety pools lined with college applications that require high grades and “voluntouring” at an organic farm in the Global South; or b) quicksand that enables low motivation and necessitates that Mom fills out college applications for the child.

Let’s all just focus on being happy, the movie says. If you’re happy, you’ll win. Your kids will be happy. And if you’re happy as a mom, you’ll also get to drink wine at 9 a.m., drive fast, and become the kind of PTA president that allows some gluten in the bake sale. That’s a far better reward than hospitalization! Happiness is presented in the movie’s climax as being situated at the other end of the spectrum from achievement, for moms AND kids.

But could it be that gaining happiness is just another form of achievement that could land us right back where we started? This happiness v. achievement rhetoric is everywhere. Books that make happiness a project for moms, and books that critique the “science of happiness.” Viral posts about teachers opting not to give any homework this year because it makes kids and parents and teachers miserable. Articles that extoll the virtues of women’s self-care, and articles that critique self-care as a form of soft-core neoliberal brain washing. Indexes of happiness referencing the happiest places where you should all live. And many parents, at some point when talking to children, saying, “What matters most to me is that you’re happy,” while mentally finishing the sentence with “…and obviously that you leave home before you turn 35.”

Earlier we asked whether it was good or bad to reference slugs when talking about our children’s lunches. But very few things in motherhood are about “or,” and comparing real experiences to extremes, even if they’re switched in a comedic way to call attention to their absurdity, may trap us into thinking we’re not doing anything right.

The moms in the movie were at their funniest and, dare we say, happiest, when expressing anger and letting go of all of their achievement demands. Plus they liked each other a lot more. As we finish up our school supply shopping and the kids head back to school, perhaps we ought to be cautious not to fall into the trap of making happiness yet another high achievement that good (bad?) moms have to add to the list.

Michelle Janning is Professor of Sociology at Whitman College, and Chair of the Council on Contemporary Families. She has a blog (www.michellejanning.com) where she wrestles with the realities of social life, which usually requires looking at them as gradations rather than extremes. She is trying to get her garden slugs under control.

Emily Tillotson is Director of the Bachelor of Social Work Program and Assistant Professor of Sociology and Social Work at Walla Walla University. She loves to consume pop culture in all forms through a decidedly feminist lens.

Meagan Anderson-Pira is a non-profit director with a Master’s Degree in Psychology who loves talking with sociologists (see above) while watching reality television and funny movies.

All three authors live in Walla Walla, Washington, where thankfully there is a 12-screen movie theater.

Comments 1

Joanna Van Brunt — September 14, 2016

Society has put so much pressure on parents, especially moms. If you really think about it, no matter what you do, you will never be good enough. You will not make everyone happy, and you will not always be happy as well. But that is perfectly okay. It is okay to not be perfect.

Personally, I have not seen the movie “Bad Moms.” Judging by this article, the movie is suggesting that if you are happy, then you can make others happy. The older generation believes that if you put everyone before yourself, then you will be happy. If you follow one of these, there is no resolution. As long as you make yourself valuable and make yourself part of the list, then you can figure out where that happiness is found.

Everyone has a tipping point in which there emotions pour out without any control. If you need to express your frustration, like these moms apparently had done in the movie, there is nothing wrong with that. However, you have to control that. There are no rules, even though this world would like there to be. What you do matters.