A terror attack takes place.

A large protest breaks out.

A natural disaster occurs.

A prominent public figure dies.

In the earliest minutes, while news networks are scrambling to give the event a name, vernacular users on Instagram offer a flurry of hashtagged tributes with text post prayers, stock photography, and artful homages.

Soon, a primary hashtag and emblem for the event emerges: The yellow umbrella for #OccupyCentral, the Monumen Nasional for #KamiTidakTakut, the Eiffel Tower for #PorteOuverte, silhouettes of the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew for #PrayForLKY.

Yet, alongside these consolations are Instagram users who attempt to appropriate the attention current of these trending channels for self-publicity, flooding dedicated hashtags with scarcely relevant selfies, outfit of the day shots, wares for sale, and redirected links.

How do we make sense of this?

It’s been an agonising series of weeks after a string of grievous events in various parts of the world. I have been tracing vernacular responses to global grieving events on Instagram since 2014, and some of the case studies are archived here.

However, of late, global tributes on trending hashtags have been featuring a more prominent disdain for, rejection of, and critique on public grieving in memes and “thoughts & prayers” en masse.

In this post, I trace the various global grieving hashtags on Instagram and mull over the presentation of grief in public digital spaces.

A “grief aesthetic” on Instagram

In my on-going project tracking the earliest vernacular reactions to global grieving moments (i.e. #OccupyCentral, #CharlieHedbo, #PrayForLKY, #PorteOuverte, #KimaTidakTakut) on Instagram, I developed a register of visual tropes most viable for social media virality during social movements, or what I term a “grief aesthetic” on Instagram.

These “public grieving” elements comprise:

1) An iconic visual symbol with cultural significance to the grief event, such as a national landmark or an instrument signifying victims or perpetrators. These may be illustrations, photographs, or various art forms (i.e. the Eiffel Tower for #PorteOuverte, the pencil for #CharlieHedbo, silhouettes of Mr Lee Kuan Yew for #PrayForLKY, national flag for #KimaTidakTakut).

2) An iconic image/scene from “the ground” that captures the essence of the movement, such as a prominent victim or perpetrator photographed in action, or a group of actors performing a powerful gesture (i.e. hands raised in surrender for #OccupyCentral, snaking queues to pay last respects for #PrayForLKY).

3) Emblems borrowed from a lexicon of political statements and redesigned for the event (i.e. the yellow ribbon for #OccupyCentral, the peace symbol incorporating Monumen Nasional for #KimaTidakTakut).

4) #PrayForX typesetting in various artistic fonts and illustrations, usually printed on a plain coloured background or superimposed onto a background image of iconic landmarks, scenes, or scenery.

5) Keep Calm and X advice typesetting in various fonts and illustrations, usually appealing to the power (i.e. Keep Calm and Pray for Paris) of prayer, or an often risky and ill-timed comedic relief (i.e. Keep Calm and Eat Baguettes).

6) Emblems borrowed from popular culture and repurposed for the event (i.e. Where’s Charlie comic for #CharlieHedbo, Guy Fawks mask for #OccupyCentral).

7) Images of event-specific paraphernalia peddled to users (i.e. yellow ribbons for #OccupyCentral, silhouette artwork for #PrayForLKY).

8) Screengrabs of event-related news updates, usually cross-posted from other social media such as Twitter and Facebook, or mainstream television.

Grief hype-jacking

While the elements of “grief aesthetic” on Instagram have emerged as vernacular norms of acceptable “public grieving” visibility practices, some users tap into this global current of attention in less palatable ways.

In “public grieving”, users sincerely partake in a global expression, narrative, and dialogue of a grief event through the use of high visibility trending hashtags. In “publicity grieving”, users opportunistically harness the attention currency of high visibility trending hashtags to promote their brand and wares. I term this phenomenon of bandwagoning on public tributes and high visibility hashtags “grief hype-jacking”, as users wrestle to misappropriate highly public channels of collective grief for self-publicity.

Although many users who “grief hype-jack” are ordinary everyday Instagrammers, microcelebrity (Senft 2008) Influencers and celebrities tend to be the most prolific since their craft is premised on a firm command of the attention economy (Goldhaber 1997). Influencers are shapers of public opinion who persuade their audience through the conscientious calibration of personae on “digital” media such as social media, supported by “physical” space interactions with their followers in the flesh (Abidin 2015).

The attraction and mystique of Influencers is largely premised on their ordinary, mundane, everydayness. However, personal failures, grim self-reflections, and public performances of grief are often re-narrativised and hyper-visibilised alongside their highlight reel of self-branded achievements to a watchful, responsive audience as a self-conscious display of vulnerability. In other words, while Influencers may experience genuine sorrow and grief, many of them conscientiously curate the outward expression of such grief to fish for empathy, relatability (Abidin 2015), and publicity. More crucially, as Influencers and celebrities the wares being hawked are often the self-as-brand per se, chiefly represented by such users’ Instagram feeds.

Davenport & Beck (2001) developed three pairs of attention parameters: “voluntary” and “captive”, wherein one gives attention out of choice or not; “attractive” and “aversive”, wherein one gives attention for gains or to avoid loss; and “front-of-mind” and “back-of-mind”, wherein one gives attention explicitly and consciously or out of a familiar muscle memory. On a regular basis, Influencers command a passive form of voluntary, attractive, and back-of-mind attention from their stable stream of followers. However, Influencers may engage in spectacle-like practices to generate an active form of captive, aversive, and front-of-mind attention to recapture the foci of existing followers and attract new ones.

Publicity grieving

In recent times, Influencers and celebrities are practicing “grief hype-jacking” to different extents of success, in relation to public backlash from their followers or mainstream media. Having studied the Influencer industry since 2010 as an anthropologist, I observed some tropes of publicity grieving practices.

The elements of “publicity grieving” often mobilized in “grief hype-jacking” include:

1) Selfies and close-ups of dramatic crying or concentrated prayer in action, wherein the user is otherwise seemingly primed for the camera with carefully done hair and make-up. Followers have sarcastically called this out as “glamorous crying” or “fake crying”.

2) Outfit Of The Day or #OOTD images, in which the user poses for the camera in fashionable clothing awkwardly juxtaposed against an unrelated outpour of grief and consolation in their caption. Here, it is clear that the main feature is one’s outfit and self-as-brand, and the misalignment of image and caption has been called out by followers as “attention whoring”.

3) Photographs of the user at a landmark of scenic place relating to the grief event, usually from a past travel. Users often overstate a personal connection to the event or place by emphasizing just how recently they had visited (i.e. “it’s been two years but it feels just like yesterday”), how geographically close they had been to the site of grief (i.e. “I can’t believe we stayed just three blocks from this place”), the (arbitrary) emotional ties they feel to the place (i.e. “I have always enjoyed the country”), and how they share equal rights in the vulnerability of current victims and grievers (i.e. “if this happened when I was there, I could have died”). Followers have called out such practices as “riding a trend” and being “narcissistic”.

4) Photographs of the landmark or a scenic place relating to the grief event, usually copied and reposted from other sources unrelated to the user themselves. Users often have not personally visited the place, but re-gram photographs taken by (semi-)professional photographers on Flickr, Pinterest, or Instagram and insert captions of consolation and grief clouded in the rhetoric of authenticating practices. These authenticating practices serve to create and convey a user’s personal connection to the place, where there was previously none, through the admission of romanticizing grief (i.e. “everyone’s recent tributes from their travels made me wish I had visited before the incident”), aspirational travel plans (i.e. “I’ve always wanted to visit this place”), and superimposed empathy (i.e. “I can’t imagine if this happened to my own country”).

5) Overt advertisements of products and services on offer, usually accompanied by redirected URLs, user handles, or sponsored hashtags in the caption. These spam-like posts are the most cluttering of the “publicity grieving” practices, and are least used by Influencers and celebrities for whom the impression of being “hard sell” is fervently avoided (Abidin & Ots 2015).

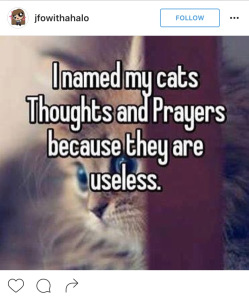

#thoughtsandprayers

Evidently, there is a shift from “public grieving” to “publicity grieving” alongside the proliferation of “grief hype-jacking”. While the “grief aesthetic” elements on Instagram have emerged as vernacular norms of acceptable “public grieving” visibility practices, some users tap into this global current of attention in less palatable ways. Perhaps it is for this reason that the backlash against #PrayForX and #thoughtsandprayers memes has been growing.

How are ordinary users on Instagram responding to this?

To find out, I trace the #thoughtsandprayers hashtag on Instagram and the content posted for a ten-day period between 10 July 2016 and 19 July 2016.

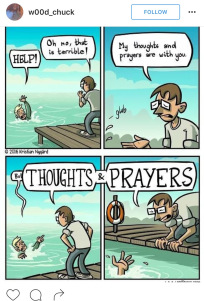

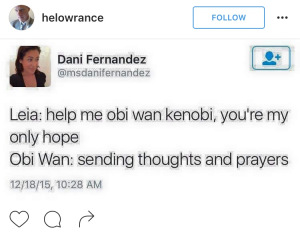

Saturation fatigue regarding the newest onslaught of passive “internet solidarity” and satirical remixes of #thoughtsandprayers were displayed in brilliant comics.

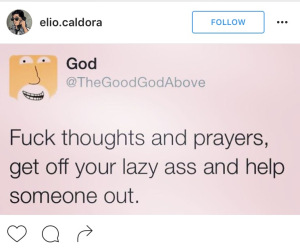

At times, users adopted the persona of a higher power/presence to portray angry or humorous responses.

Some users adopted the #firstworldproblems approach to expose the casualness and frivolity at which people were jumping on the #thoughtsandprayers bandwagon.

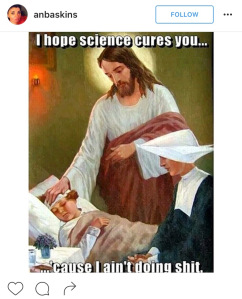

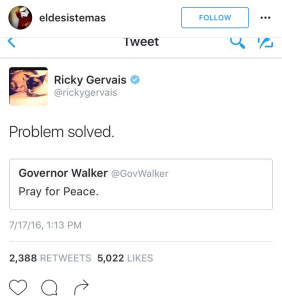

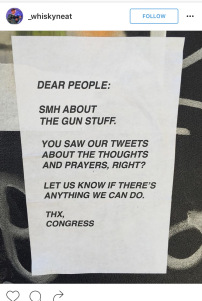

Other users simply displayed their outright rejection of users sprouting #thoughtsandprayers on social media, alluding to a displaced sense of pseudo-activism, and inflated impression of aid, and a general ineffectiveness despite participation in a highly visible and populist activity that still promotes passive solidarity from a distance.

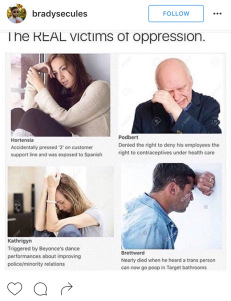

A handful of users mobilised #thoughtsandprayers as a meme to shed light on ineffective political governance and leadership, and the cyclic routine of public grieving.

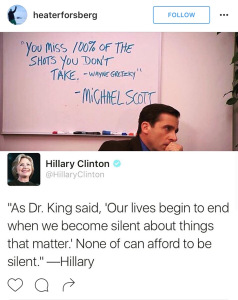

Speaking of memes, users are also using #thoughtsandprayers in an ironic manner to display contempt for developments in politics, and in a humorous manner to express tongue-in-cheek suggestions to better the state of political participation.

How do you feel about public grieving and publicity grieving in response to global tragedy? Have you experienced saturation fatigue yourself? What other things have you noticed about the rampant use of thoughts&prayers?

Feel free to beep or write to me.

The concepts of “public grieving” and “publicity grieving” are based on my recent talks at the Asia Research Institute (ARI) and Tembusu College this March. (See event archives here: Homo Sapiens, Mortality and the Internet in Contemporary Asia | Tembusu STS Seminar: Reflections and Discussion.) These works have been commissioned for a forthcoming journal article and a book chapter.

Dr Crystal Abidin is an anthropologist and an ethnographer. Reach her at wishcrys.com and @wishcrys. A version of this paper will be presented at the AoIR 2016 in Berlin this October. A version of this post was first published on wishcrys.com.