Overview to a six-part series examining the origins, progress, and future of welfare reform. Over the next six weeks, The Society Pages will publish the individual reports.

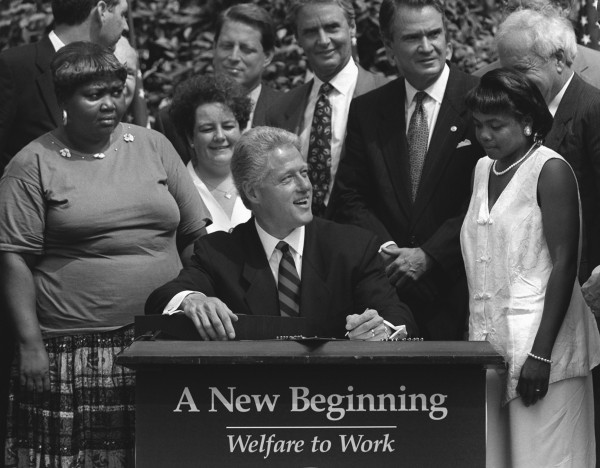

Twenty years ago, President Bill Clinton proposed to “end welfare as we know it,” and, on August 22, 1996, he did just that when he signed into law The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). This welfare reform repealed the cash assistance program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), and replaced it with a program called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF).This wasn’t just an alphabet soup change-up; it effected a significant transformation in policy, based on an amalgamation of old racial prejudices and new expectations about families, women, and self-reliance. That is the conclusion of six new papers presented to the Council on Contemporary Families for their Welfare Reform at 20 Online Symposium. As University of Maryland demographer Philip Cohen demonstrates, the PRWORA reflected changing norms about the employment of mothers along with an abiding hostility towards black women. Stephanie Coontz of The Evergreen State College points out that it also embodied several myths about the history of the War on Poverty. One result of these myths was a growing diversion of welfare funds to programs designed to promote marriage and responsible fatherhood. But as Cal State-Fresno sociologist Jennifer Randles’ in-depth study of these programs reveals, they did not increase marriage rates or relieve poverty. Indeed, the few benefits they conferred came despite their out-of-touch condescension towards poor families, not because of the middle-class values and skills they tried to teach.

The Act succeeded in reducing the number of families receiving assistance: In 1996, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 4.4 million families received aid, and in 2012, 1.9 families received aid. Yet it failed at reducing the need for assistance, as documented in legal scholar Shawn Fremstad’s examination of the state of millennials. In 1996, 5.6 million families were in need; in 2012, 5.7 million families were in need.The Act was initially deemed a success because more single moms found paid employment and the employment rate reached historic highs, CEPR’s domestic policy director Alan Barber and Framingham State University sociologist Virginia Rutter report. This employment surge, though, started in the early 1990s, well before welfare reform. Furthermore, the job losses starting in the 2000s have not been mitigated by this program, leading to intensive instability, especially for very poor families, per American University economist Bradley Hardy. Notably, child poverty today is as high as it was when President Lyndon Johnson announced the War on Poverty in 1964.

Why reform? It’s the attitudes.

As Philip Cohen reports: “If there was one thing the majority of Americans could agree on in 1996, it was that people on welfare were a big problem…. In April 1996, 77 percent of Americans told the Gallup poll that taking action on welfare was either ‘very important’ or a ‘high/top priority.’” In Welfare Reform Attitudes and Single Mothers’ Employment after 20 Years, Cohen documents how married mothers’ growing employment rates interacted with racism to cultivate negativity toward the cash assistance program for single mothers that had been expanded by Presidents Johnson and Nixon.

Ironically, while welfare programs are seen as a pet of liberals, Cohen charts how hostility against welfare has been lower in years when a Republican is in the U.S.’s highest office, and higher when a Democrat is president. Fremstad notes that President Richard Nixon even supported a minimum national income and advocated ending unequal benefits across states, arguing that “no child is ‘worth’ more in one State than in another State.”

The way we were and could have been.

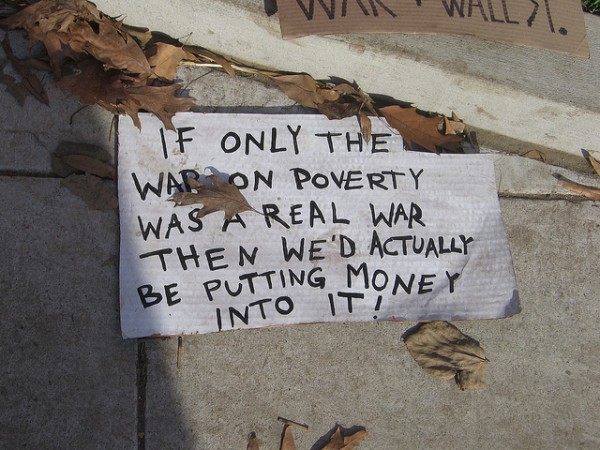

The negativity of the 1990s, according to historian Stephanie Coontz in Welfare Reform’s 20th Anniversary, also reflected a revisionist history of the anti-poverty measures passed under Johnson and Nixon. President Ronald Reagan fanned the skepticism of the 1980s: “We fought a war on poverty, and poverty won.” In fact, the 1965 war on poverty programs reduced poverty by nearly half.

Some criticisms of the old model were legitimate. “AFDC tended to penalize work and encourage under-the table ways of earning money because the grant was reduced if a recipient earned or reported any extra income,” explained Coontz. “The work deterrent was much more modest than often assumed, but it was real.” Still, the solution was draconian: The 1996 law abolished AFDC’s guarantee of cash assistance to all eligible poor families. It gave states a fixed pool of money for income support and work programs, along with “considerable leeway about how – or whether — to spend that money.” Louisiana, Michigan, and Missouri are among the states that cut direct benefits and diverted funds to other uses. The federal government also allocated new funds for programs to promote marriage as a solution to poverty, an agenda that became increasingly central to welfare policy in the early 2000s.

Marriage promotion didn’t reduce poverty.

Over the past 20 years, one billion dollars (total) of welfare funds have been directed at programs aimed to increase marriage rates and thereby reduce poverty. In The Frontlines of Welfare Reform: Why Marriage and Responsible Fatherhood Programs Succeed or Fail, sociologist Jennifer Randles reviews studies of welfare-funded couples workshops that targeted poor families.

As Randles points out, none of these programs has been shown to reduce poverty or increase marriage rates. Couples did experience some benefits from some of the programs, but not for the reasons the organizers originally thought. “Instead of being magically transformed by mentors or experts into stable middle-class partners, couples in these classes ended up learning from each other that their relationship and parenting challenges are shaped by economic stress and race, class, and gender inequalities, not just their own or their partners’ shortcomings,” explains Randles.Fathers appreciated programs that gave them the “opportunities, resources, and social support they needed to be there for their children, and didn’t just lecture them about financial responsibility.” But Randles quotes Christopher, a 22-year-old, African-American father of one young son: “There was nothing else after. It’s not like we finish the program and get an interview or start another program. Other guys went back to the street after the program, just doing what they can to make a dollar…. We went from being on this block every day, to making it to class every day. It became a priority for us. We’re trying to better ourselves, but what are we supposed to do now? We got a certificate, now what?”

Let’s try a little economic and policy research.

CEPR’s Alan Barber and sociologist Virginia Rutter offer a targeted report on the employment dynamics of single mothers without a high school degree. A single graph in TANF didn’t fight poverty. Full employment did, tells all. The rate of work among single mothers—who were disproportionately African American—rose prior to welfare reform, and continued into the late 1990s. In that period of time, TANF use declined. When jobs began to disappear in the early 2000s, welfare dependence remained low, but poverty and hardship began to rise again because welfare was not acting as a safety net.

The safety net for the poorest of the poor is the focus of economist Bradley Hardy, assistant professor of public policy at American University. In examining family stability in the past two decades, Hardy notes that poor families don’t just have low incomes, they have volatile incomes, with no savings or wealth to buffer them against layoffs or emergencies. TANF reforms, which removed any kind of income floor, “resulted in a weakened cash-based safety net….For such families, there is oftenno adequate substitute for cash assistance to pay bills—near-cash programs providing important food and housing assistance will not buy a coat, bus fare, or emergency auto repairs,” he notes in TANF Policy to Address Low, Volatile Income Among Disadvantaged Families.What about the Next Generation?

“Millennial parents should be the most prosperous parents in history,” writes Shawn Fremstad, who has worked on TANF, labor market and related policies since the 1990s. “In addition to being better educated than any previous generation and waiting longer to become parents, they are raising children in an economy that is 70 percent more productive than when Baby Boomers were the same age. Yet, roughly one out of every five (20.6 percent in 2014) live below the federal government’s outdated and increasingly austere poverty line ($24,000 for a married couple with two children). This is about twice the rate of their counterparts in 1979.”

Yet only 21 percent of poor parents aged 20-29 were receiving TANF in 2013. In Is TANF Working for Struggling Millennial Parents? Fremstad shows how TANF has whittled away needy parents’ access to resources. Those fragmented policies have led to just the disparities that Nixon sought to eradicate back in the 1970s: because of variations in services and generosity, Massachusetts ranks first, while Mississippi ranks last in Annie Casey Foundation child well-being ratings.

Now what?

As Coontz argues, several policies initiated in the 1990s have been effective in reducing material hardship among those able to find and hold on to jobs. But high unemployment rates, low wages, and the inaccessibility of childcare means that many poorly-educated parents, especially single mothers, cannot work enough to take advantage of programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit. And the end of cash assistance for these families has greatly increased the hardships of the poorest of the poor. Cohen sums up: “There is a sad irony here, one that is familiar to students of racial conflict in U.S. history. We had a moment in which single and married mothers – all moving toward higher employment rates – might have benefited from improvements in work-family policy for all families. This might have improved child well-being and reduced gender inequality at a time when women’s rising employment was reaching a limit under the existing policy regime. Instead, however, we ended up with a punitive policy directed at poor single mothers – and little progress on work-family policy for the next two decades.”

For more information, contact:

- Alan Barber, Director of Domestic Policy, Center for Economic and Policy Research, barber@cepr.net

- Philip Cohen, Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Maryland, pnc@umd.edu

- Stephanie Coontz, Professor of History and Family Studies, The Evergreen State College, coontzs@msn.com; 360-556-9223

- Shawn Fremstad, J.D., Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress and Senior Research Associate, Center for Economic and Policy Research, sfremstad@americanprogress.org

- Bradley Hardy, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Policy and Administration, American University,hardy@american.edu

- Jennifer Randles, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, California State University, Fresno,jrandles@csufresno.edu; 559-906-9842

- Virginia Rutter, Professor, Department of Sociology, Framingham State University, vrutter@gmail.com

Comments 2

JDF — August 24, 2016

Pretty well, actually. Cherry picking can be fun though.

Joanna Van Brunt — August 29, 2016

Welfare is a hard topic to talk about. Growing up with my family, we were always raised to work for what you want. We were never handed anything. I currently work at a bank, so I see individuals come in and seek money that they do not have. A lot of the time, it is because they are unemployed and waiting for their check to come in from the state. Where does that money come from? Individuals who work full time jobs are the ones who pay for that through a wonderful thing called taxes.

This article only proves to me that times have changed when it comes to work. People are no longer looking for jobs that they were seeking back then. They want to come up with excuses as to why they can not work. I know that this country provides more than enough jobs for its citizens, because we have people from other countries looking and begging for jobs that some take for granted. It is a matter of "want to."

This article shows that people wanted to work and wanted to be successful no matter their background. They wanted to prove a point that they were more than capable. Jobs were found, and goals were reached. However, it seems as if a lot of people do not have goals anymore. They just want to get by. Take advantage of what is given to you.