Mattel, creator of the Barbie doll, has launched “a doll line designed to keep labels out and invite everyone in—giving kids the freedom to create their own customizable characters again and again.” This doll has minimal makeup, a short hairstyle with an attachable long-hair wig, a flat chest, flat feet (for wearing sneakers, hiking boots, or platform sandals), and clothing that includes femme and butch options. The clothes and accessories can, of course, be interchanged into dozens of different combinations.

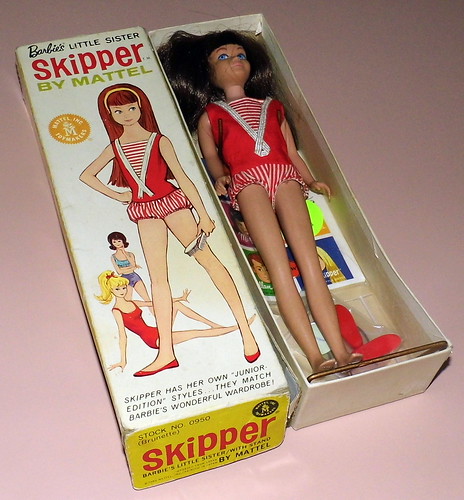

For those old enough to remember the 1960s dolls, I have one word for you: Skipper. For those too young to know, Skipper was Barbie’s little sister and had a pre-pubescent body: flat chest and flat feet, since she was too young to wear heels. Imagine Skipper only with hair that could go off and on, and a more expansive wardrobe (which, in the 60s, we would have called “tomboy”).

In fact, Mattel sidestepped controversy by diplomatically calling the new doll “customizable” rather than gender-inclusive. This doll does not include adult body types at all. It is more of a genderless kid than a gender inclusive adult. For gender inclusion recognizes that policies, programs, and language need to be broader to encompass the fluidity of gender expression and orientation. According to Gender Spectrum, the organization whose mission is to create a gender-inclusive world for all children and youth, gender inclusivity means being open to everyone regardless of their gender identity and/or expression. Gender inclusion would thus include people with large breasts who identify as men and people with penises who identify as women.

Of course, Mattel’s 12-inch plastic dolls were never particularly realistic, and never had genitalia. In addition, anyone with even an ounce of creativity could, and did, dress their Barbie doll in the clothing that came with a Ken or G.I. Joe doll, cut off Barbie’s hair, pierce Ken’s ears, draw on tattoos, create their own accessories, and so on.

Interestingly, Mattel has already made Barbie dolls dressed as men. Between 2011 and 2019, Mattel released an Elvis Barbie, a David Bowie Barbie, a Frank Sinatra Barbie, and an Andy Warhol Barbie. These are standard buxom Barbie dolls dressed as the iconic male figures. Some might consider these dolls at least as gender-bending as the Creatable WorldTM dolls. But they are also less threatening because they are marketed to adult collectors, not to kids who will play with them. And Mattel has yet to create Marilyn Monroe Ken or Barbra Streisand Ken. (If you’re listening, Mattel, I’ll accept royalties.)

Changing your Barbie’s skin color was a little more challenging, but by 2009, Barbie’s 50th anniversary, Mattel had released far more ethnically diverse Barbies, although they were still primarily princesses, graceful goddesses, and buxom movie stars. Over its nearly 60-year history, Barbie’s body shape remained a lingering complaint of feminist critics, well after Barbie got more racially diverse and Teen Talk Barbie no longer said “Math class is tough.” For even the pilot and presidential candidate Barbies had big chests and really tiny waists, making one wonder if she would hit that glass ceiling pointy boobs first. Sure, it could be seen as a sign of strength that Barbie does everything Ken does, only in downward pointing feet that only fit in heels. But as millennials began to become moms who buy (or refuse to buy) Barbies (see, e.g., this feminist mom’s explanation), and Mattel’s sales started to plummet, Mattel began to rebrand itself in 2016 with the launch of new Barbie body types—petite, tall, and curvy.

Perhaps Lena Dunham, whose nudity in Girls was considered transgressive, deserves thanks. We should also thank the artists and activists who had a dream for Barbie and used social media to share it, going much farther than Mattel to re-imagine Barbie, gender, and pop culture. Indeed, they make Creative WorldTM dolls look pretty conventional. The changes Mattel has been making can be seen as a direct result of the willingness of artists, activists, and fans to playfully engage with—rather than simply criticize—their dolls. Creatable WorldTM dolls may be another step Mattel is taking to embrace diversity and include more consumers. How far it will go might once again depend on what fans of the dolls demand and how creative people get in making their own visions known.

Martha McCaughey is Professor of Sociology at Appalachian State. She blogs on sexual assault prevention at See Jane Fight Back (www.seejanefightback.com)

To

To