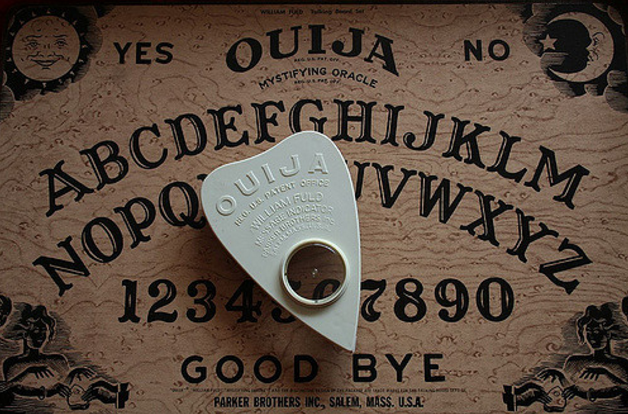

To begin, it wasn’t just a toy. It debuted in 1890 and it was the next in a long line of devices that had been invented to allow people to communicate with spirits. These weren’t intended to be pretend; they were deadly serious.

According to Lisa Hix, who wrote a lengthy history of such devices for Collector’s Weekly, the mid-1800s was the beginning of the spiritualist movement. People had long believed in spirits, but two sisters by the name of Fox made the claim that they could communicate with them. This was new. There were no longer just spirits; now there were spiritualists.

Amateur historian Brandon Hodge, interviewed by Hix, explains:

Mediums sprang up overnight as word spread. Suddenly, there were mediums everywhere.

At first, spiritualists would communicate with spirits by asking questions and receiving, in return, a series of knocks or raps. They called it “spirit rapping.” There was a rap for yes and a rap for no and soon they started calling out the alphabet, allowing them to spell out words

Eventually they sought out more sophisticated ways to have conversations. Enter, the planchette. This was a small wooden egg-shaped device with two wheels and a hole in which to place a pencil. Participants would all place their fingers on the planchette and the spirit would presumably guide their movements, writing text.

These were religious tools used with serious intentions. Entrepreneurs, however, saw things differently. They began marketing them as games and they were a huge hit.

Mediums resented this, so they kept innovating new and more legitimate-seeming ways of communicating. In addition, the planchette scribbles were often difficult to read. The idea of using an actual alphabet emerged and various devices were invented to allow spirits to point directly to letters and other answers.

Eventually, the concept of the planchette merged with the alphabet board and what we now know as the Ouija board was invented.

In the 1920s, mediums came under attack from people determined to prove that they were liars. Houdini is the most famous of the anti-spiritualists and Hodge argues that he “ravaged spiritualism.”

He set up little “colleges” in cities like in Chicago for cops to attend to learn how to bust up séances, and there was a concerted national effort to stamp out fraud.

Meanwhile…

The Spiritualist believers never successfully cohesively banded together, because they were torn asunder by their own internal arguments about spirit materialization.

Most mediums ended up humiliated and penniless.

“But the Ouija,” Hodge says, “just came along at the right time.” It was a hit with laypeople, surviving the attacks against spiritualists. And, so, the Ouija board is one of the only widely-recognized artifacts of this time.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.