Sociologists are quite familiar with the combination of marginalized identities that can lead to oppression, inequalities, and “double disadvantages.” But can negative stereotypes actually have positive consequences?

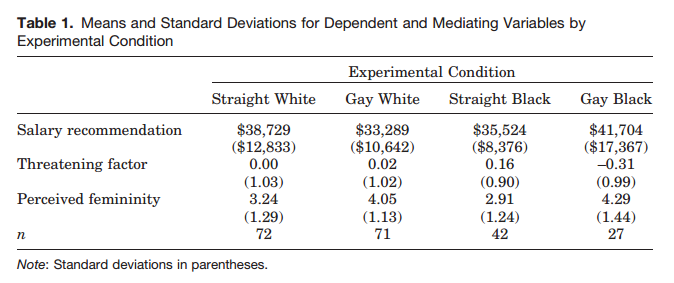

Financial Juneteenth recently highlighted a study showing that gay black men may have better odds of landing a job and higher salaries than their straight, black, male colleagues. Led by sociologist David Pedulla, the data comes from resumes and a job description evaluated by 231 white individuals selected in a national probability sample. The experiment asked them to suggest starting salaries for the position and answer questions about the fictional prospective employee. To suggest race and sexual orientation, resumes included typically raced names (either “Brad Miller” and “Darnell Jackson”) and listed participation in “Gay Student Advisory Council” half the time.

Pedulla found that straight Black men were more likely to be perceived as threatening, measured with answers as to whether the respondent thought the applicant was likely to “break workplace rules,” make “female co-workers feel uncomfortable,’’ or “steal from the workplace.” In contrast, gay Black men were considered by far the least threatening. Gay black men were also judged to be the most feminine, followed by gay white men.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the combination of being gay, Black, and male attracted the highest salaries. Gay Black men were considered the most valuable employee overall. Straight white men were offered slightly lower salaries and gay white men and straight black men were offered lowered salaries still.

Pedulla’s findings have sparked a conversation among scholars and journalists about the complexity of stereotypes surrounding black masculinities and sexualities. Organizational behavior researcher and Huffington Post contributor Jon Fitzgerald Gates also weighed in on the findings, arguing that the effeminate stereotypes of homosexuality may be counteracting the traditional stereotypes of a dangerous and threatening black heterosexual masculinity.

Cross-posted at Citings and Sightings.

Caty Taborda is a graduate student in sociology at the University of Minnesota, where she’s on the Grad Editorial Board for The Society Pages. Her research concerns the intersection of gender, race, health, and the body. You can follow her on twitter.