Michael Rothberg is the 1939 Society Samuel Goetz Chair in Holocaust Studies and Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Los Angeles. His latest book is Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (2009). He is also the author of Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation (2000), and has co-edited The Holocaust: Theoretical Readings (2003), and special issues of the journals Criticism, Interventions, Occasion, and Yale French Studies. As part of the Seeking Refuge in a Changing World Series, Rothberg was invited by the Center for Holocaust and Genocide studies to give a talk titled, “Inheritance Trouble: Migrant Archives of Holocaust Remembrance.” You can watch it here.

How did you decide to bring postcolonial studies and Holocaust studies together, and what compelled you to address interlocutions between these two realms of study?

Since graduate school I’ve had an interest in both Holocaust studies and postcolonial studies, but I thought about them for a long time as separate projects and interests. Parallel to that, I had an interest in the relationship between Jewish American culture and African American culture. It was reading Paul Gilroy’s book The Black Atlantic when it came out in the 1990s that made me realize I could bring these different fields together, and I started to do that in the conclusion to my first book, Traumatic Realism. After completing that book I discovered an essay by W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Negro and the Warsaw Ghetto,” which eventually became the origins of my idea of multidirectional memory, although I didn’t have the term at that time. I wrote an essay on DuBois and his visit to post-war Warsaw where he witnessed the rubble of the ghetto and saw the newly-erected Warsaw Ghetto Uprising monument. I thought this was a powerful response that had interesting things to say about race — especially in a comparative perspective. At the time, I thought I was working on a project on Blacks and Jews, a topic that is often grounded in an American national framework. I was interested in broadening that out into an international/transnational realm.

As I was thinking about that project, I started to discover some of the links between Holocaust memory and the Algerian War. Many of the French people who were involved in the struggle around the war – as well as many who were prosecuting it — had very real experiences of Nazi occupation or deportation, of torture, of concentration camps. It was those people who were making the links between what they had experienced in the 1940s under the Nazis and Vichy and what was happening at that moment in the conflict between France and the FLN (the national liberation movement of the Algerians). It was especially those links that crystalized the notion of multidirectional memory: the point was that at the very moment that Holocaust memory was starting to emerge as a public and global phenomenon, it was doing so in dialogue with ongoing processes of decolonization and memories of colonization, slavery, and other forms of racism. So it was through the discovery of these concrete and historically located instances of dialogue across experiences that I brought together Holocaust studies and postcolonial studies and conceptualized the multidirectionality of memory.

Multidirectional memory is an innovative way of thinking how memory works and how it can be framed in a noncompetitive way. You emphasize the need to talk comparatively about the Holocaust and moving away from a zero-sum game, understanding how genocide memories work and how they’re not crowding out or competing with each other. What happens when memory, conflict, and tension still arise from debates about the uniqueness of the Holocaust? Can competition still exist in this multidirectional framework?

There’s no doubt, and I’m not trying to ignore the fact that there’s a great deal of memory conflict and there’s a great deal of competition around memory and articulations in the public sphere — that’s absolutely the case. What I was responding to was a particular logic or way of thinking about that conflict and competition, which I ultimately identified with the logic of the zero-sum game. At the extreme, the logic of the zero-sum game suggests that if you have one memory, you can’t have another memory at the same time. It struck me that this was a logic you found on different sides of memory conflict.

In other words, for those who were concerned about preserving the so-called uniqueness of the Holocaust there was a concern that linking the Holocaust to other histories of trauma, violence, or racism was in fact a form of Holocaust relativization or Holocaust denial. But on the other side, you had very similar phenomena: those who were eager to articulate memories of, let’s say, the genocide of indigenous peoples, slavery, colonial crimes, and so on, also had a sense that it was the presence of the Holocaust in the public sphere — which has absolutely been more central than many of those other memories — that was the cause of the paucity of memories of colonialism, slavery, etc. Although I understand the impetus for those claims, that logic just seemed to me wrong. Logically speaking, but also in practice, it wasn’t the presence of the Holocaust museum in Washington D.C. that was preventing the memory of American crimes against humanity from being articulated—there were other things that were preventing that. The presence of Holocaust memory could, in fact, be what I call a “platform” or “occasion” for making articulations that would start to bring those other histories into discussion.

Public memory kind of works in a cross referencing way, maybe more memories are produced from interaction of these memories.

That’s my theory! I still hold to it even though there might be a tendency to think of this as a strictly celebratory model–the notion that “memory is multidirectional, isn’t that great, problem solved.” That’s really not the point I make. In fact, I start the book with what I consider a very negative example of a harsh articulation of a competitive position, setting African American memory against Jewish memory. I don’t start with a model of reconciliation, but with a model of competition. But what I try to show is that even in that moment of competition we find the reliance on the fact of Holocaust memory having been articulated in order to articulate another tradition of memory. The relation between the memory traditions turns out to be more productive than it looks at first.

Taking that sentiment to heart, you also write about this in the context of migrants in Germany. In an essay you co-authored with Yasemin Yildiz, you write that as collective memory scholars we must make it crucial to take migrants seriously and understand that they are also a part of this grid; we need to take them seriously as subjects of national/transnational memory rather than passive objects of commemoration. Can migrants or those with a migration background also become implicated within Germany’s past or, perhaps, “integrate” into Germany’s past and memory culture as Zafer Senocak once said?

That’s a great question and gets to the heart of the two larger projects I’m working on now. One of those projects is a co-authored book with Yasemin Yildiz on the way that immigrants, especially Turkish-German immigrants, negotiate with German Holocaust memory culture. Then, there’s another book that I’m writing parallel to that, called The Implicated Subject, which takes up the broader question of what it means to be implicated in histories of violence, especially histories that you have not participated in directly. Those two projects overlap, obviously.

I think, in a certain sense, you can’t live in Germany and not come to terms, in some way, with Germany’s history. I think that would be true of any country. I don’t think you can immigrate to the United States and not come to terms in some way with the histories of genocide, slavery, segregation, and more that have marked our country. Which doesn’t mean we always do it very well at all, but rather that there’s an ethical imperative to engage with those histories, and I’m interested in that in the American context as well as the German context.

The German context is tricky in a couple of different ways because, as the land of the perpetrators, so to speak, it’s very clear why there had to be the development of a very serious culture of historical responsibility. That development has gone through many stages. There’s always been a lot resistance and hesitation; it’s by no means as clear a success story on all levels as it’s often made out to be when people talk about the German model of coming to terms with the past. But something has certainly been accomplished, you can’t deny that. In that context, to go back to the multidirectionality issue, the question of comparison of the Holocaust becomes very charged and very difficult. Nowhere have I seen as serious strictures on comparison of the Holocaust as I have in Germany among non-Jews. It is understandable because it is linked to a taking of responsibility — it is often articulated as “our responsibility” — and any kind of comparison would be a relativization of “our responsibility.” That’s understandable but it also produces perverse results at times, especially when it concerns people who are not considered “German” yet who may find themselves living in Germany or being German citizens. That’s where the question of migration comes in.

What we have found in our joint project is that in the last 15 years especially, immigrants to Germany have been subjected to what we call a “migrant double bind,” which is to say that, on one hand, they are told that in order to be German they must take responsibility for the Holocaust, but, on the other hand, they hear people say: “you migrants aren’t German, therefore this is not your history; stay away, you’re probably anti-Semitic anyway, you’re certainly not interested, this is our history.” There’s a paradoxical situation that arises in which to be German — to have full citizenship in a cultural/social sense — you have to take part in Holocaust memory discourse; but at the same time, you’re constantly pushed away from that as you are from everything that is considered German, including the language, cultural heritage, etc. But the Holocaust is a particularly central node of what it means to be German in unified Germany, so this is a significant bind that migrants find themselves in.

A follow up to that: I’m thinking of something that happened last year in April 2017, in the context of the far-right in Germany. At that time, the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party published a Facebook post “defending” the Jewish community in Germany as news broke that a fourteen year old Jewish student faced anti-Semitic bullying from his classmates, who were of Arabic and Turkish origin. AfD capitalized on this, with former party leader Frauke Petry claiming that her party “is one of the few political guarantors of Jewish life, including in times of illegal anti-Semitic migration to Germany.” This speaks to how migrants, particularly Muslims targeted by the far-right in Europe, are often accused of not inheriting the past and, using this language of the double bind, not inheriting responsibilities of the past. Do you think this double bind is complicated at all with the recent validation of far-right discourse?

That’s an interesting question and something I will be talking about tonight in my lecture — not that particular case, but the issue. You know, I certainly don’t want to deny that there is anti-Semitism among immigrants to Germany — Muslim or otherwise. It’s a very complicated issue; in a lot of ways, a lot of it does end up intersecting with the question of Israel and Palestine. That doesn’t mean that anti-Israel/anti-Zionist discourse isn’t sometimes anti-Semitic but, I think, in Germany it tends to be automatically collapsed into anti-Semitism. So sometimes what is in fact a critique of Israel gets automatically re-coded as anti-Semitism. And again, it’s not impossible that some of that discourse is anti-Semitic but there’s a kind of assumption that it always is and I don’t think that’s the case. I think that does filter into a lot of these everyday interactions as well, which is not an excuse for them — they’re real, yet at the same time I think you have to look more broadly at German society and see who, in fact, are the perpetrators of most anti-Semitic deeds in contemporary Germany. It’s not Muslim immigrants, it’s the far-right. Statistics are tricky, and I don’t always find them entirely reliable, but pretty much every study I’ve seen recently asserts that a very large majority of those kinds of anti-Semitic incidents are perpetrated by ethnic Germans, presumably on the right.

You can’t simply displace the responsibility for these kinds of things on a scapegoated minority community, who themselves are suffering the same number of racist attacks from the far-right. Again, this is complicated terrain, but I think it argues pretty strongly against the attempt by the right — and not only the right but liberals and centrists — to scapegoat Muslim communities for acts that are actually more widespread among ethnic Germans. So, in the example you mentioned, you have a neo-fascist group trying to assert, in a very insincere way, solidarity with the Jewish community while trying to divide them from other religious/ethnic/cultural minorities in Germany. That is a devious action on their part and very obviously hypocritical, but that goes without saying.

Right, this is coming from a far-right party that’s saying that the collective guilt surrounding the Holocaust has been “worked through.” You have AfD members saying that the Holocaust memorial in Berlin is a “monument of shame.”

It’s a strategy that they’re using and it’s not uncommon; I don’t think it’s only the AfD and I don’t think it’s happening only in Germany. Again, it’s not entirely crazy and irrational from a political perspective because there are Jews on the right who would, in fact, buy into this kind of discourse, and would rather make an alliance with far-right parties than with other minority groups.

It also reveals, as you’ve written before, that Holocaust memory can function to “re-ethnicize” identity in contemporary Germany. What room is there for push back against that from a migrant’s perspective or somebody with a migration background who does consider themselves to be German?

That’s primarily what our project is about. We start out by laying out the framework of what we call the “German paradox” and the “migrant double bind.” We talked about the migrant double bind already, but the German paradox actually comes first and it involves the notion that in order to take responsibility for the Holocaust you have to reproduce an ethnic German identity, which, in a sense, was one of the conditions of possibility of the Holocaust; it doesn’t mean you’re reproducing a Nazi idea, exactly, but that you are holding on to an ethnicized or even racialized notion of what it means to be German.

In our project, in contrast, we’re ultimately interested in how immigrants and post-migrants creatively engage with the memory of the Holocaust – both on its own terms and by linking it to other histories in a multidirectional way. Thus, the main focus of our work is looking at cultural producers: artists, writers, performers, musicians. We also look at civic organizations who are in different ways confronting these questions of responsibility. They’re taking them on often very powerfully and articulating counter-discourses to ethnicized notions of German identity and German responsibility by saying, “Hey, we too are in Germany — we may or may not consider ourselves German or be considered as German — but we still see ourselves as part of this history, as inheriting some of these questions, and as wanting to deal with them by virtue of where we live – and what we inhabit, not necessarily ’who we are‘ but ’where we are.’”

One last question I want to ask in the context of your work concerns race: scholars in History and Comparative Literature, such as Rita Chin and Fatima El-Tayeb, both acknowledged that ever since post-war Germany rejected its Nazi past, the term “race” has all but disappeared from the German lexicon and public discourse. Because Europe now relies on the term “ethnicity,” it has in, some ways, obscured the deeper realities of race and Europe’s colonial past. I’d like to ask to what extent do you think the still-held emphasis on ethnicity in Europe today has emerged from this collective memory of the Holocaust? Has this collective memory, in some ways, led to the forgetting or repression of racial categories in Europe?

That’s an important question. I don’t know if it’s forgetting or repression, but certainly there is a kind of displacement that has happened. Again, sometimes for understandable reasons, the concept of race was considered tainted after the Nazi period. But that displacement ended up reproducing some of the same problems; that’s what we’re getting at with the German paradox and the migrant double bind—which represent, in a way, the afterlife of race in Europe today. And certainly Rita Chin and Fatima El-Tayeb’s work is really important to us and foundational for studies of postwar Germany. I think this inability to see race outside the framework of National Socialism has distorted the use of the category and has problematic effects in Germany; it does make it hard to see the various other kinds of racism that continue to exist, or were historically there and yet were not visible. And so, together with other scholars like those you just mentioned – as well as Damani Partridge and Esra Özyürek, anthropologists who have been working on these questions — we are dedicated to making links between what happened in the Holocaust and what happens today. Not to say that they’re the same at all. It’s not that immigrants suffer anything like what Jews during the Holocaust suffered — that’s certainly not the argument anyone is making, as far as I can tell. But that still, there are questions of racism that are difficult to articulate in Germany and I do think it’s true that it has something to do with the centrality of the Holocaust and the particular way that the Holocaust is thought of in Germany. The Holocaust is understood as not comparable to anything else and thus it ironically sometimes blocks from view the fact that racism can work in other ways.

Along with this disinclination to compare the Holocaust to any other history, which is very strong in Germany, there’s also a real disinclination to thinking about antisemitism in relation to other forms of racism. Or even that anti-Semitism is a form of racism. That’s also a big problem, I think, and it remains controversial to even speak of “antisemitism and other forms of racism,” and to think those things together. But, to me, that’s essential to do; not again to say they’re all the same, or to collapse them into one model, but that they still belong together in our thinking and it can elucidate these different experiences to think about them comparatively. In other words, there is a need today to think relationally about Islamophobia and antisemitism, but also about anti-Black racism and anti-Roma racism — obviously a really important prejudice throughout Europe and one with very clear links to the Holocaust. The important task, in my view, is to bring these ideologies and practices into the same frame and to think them comparatively — which means in their specificity but also in their conjunction.

Christopher Levesque is a graduate student in Sociology and a 2017-18 Hella Mears Fellow at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities. His work focuses on migrant health in Germany and the United States, with emphasis on access, collective memory, and citizenship.

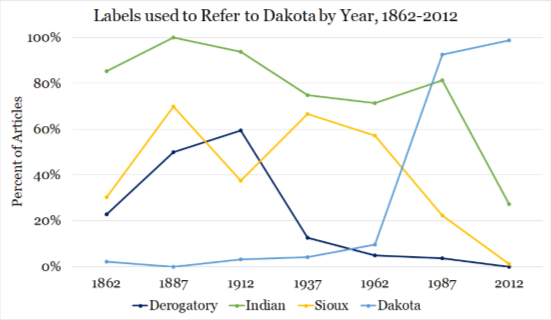

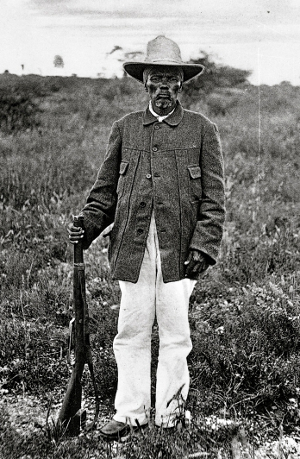

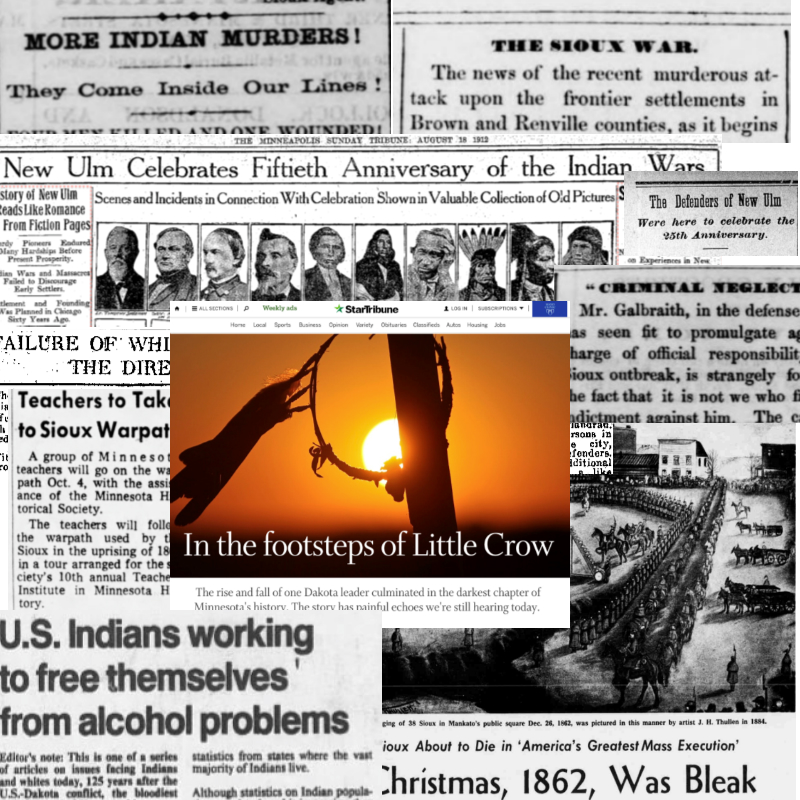

Primary data and analysis helped understand how thinking has changed over time regarding, for example, the causes of the conflict, the attribution of responsibility for the violence, or the way actors involved in the conflict are labeled (“Sioux”, “Indian”, or “Dakota” for example). Further analysis explores references to the conflict in post-sesquicentennial commemorations, including the controversial display of “Scaffold” at the Walker Art Museum last year. Overall, our findings account for progress but also highlight the persistent inequality in access to the shaping of public narratives on the Dakota people, as indigenous sources and voices continue to be rare in mainstream media.

Primary data and analysis helped understand how thinking has changed over time regarding, for example, the causes of the conflict, the attribution of responsibility for the violence, or the way actors involved in the conflict are labeled (“Sioux”, “Indian”, or “Dakota” for example). Further analysis explores references to the conflict in post-sesquicentennial commemorations, including the controversial display of “Scaffold” at the Walker Art Museum last year. Overall, our findings account for progress but also highlight the persistent inequality in access to the shaping of public narratives on the Dakota people, as indigenous sources and voices continue to be rare in mainstream media.