There is no state that has been and continues to be as haunted by the specters of a criminal past as is Germany. What happens when State leaders cannot tell a positive story about the nation’s past? A damaged national identity is, of course, not unique to Germany. For German leaders, however, the task at hand was, and continues to be, the mastering of a past that has become the symbol of ultimate evil. Jeffrey Olick’s The sins of the fathers: Germany, memory, method examines, with an impressive wealth of documentation and meticulous attention to detail, the process by which the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) confronted the burden of the Nazi crimes and dealt with its political costs.

There is no state that has been and continues to be as haunted by the specters of a criminal past as is Germany. What happens when State leaders cannot tell a positive story about the nation’s past? A damaged national identity is, of course, not unique to Germany. For German leaders, however, the task at hand was, and continues to be, the mastering of a past that has become the symbol of ultimate evil. Jeffrey Olick’s The sins of the fathers: Germany, memory, method examines, with an impressive wealth of documentation and meticulous attention to detail, the process by which the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) confronted the burden of the Nazi crimes and dealt with its political costs.

Germany’s ‘legitimation profiles’

Jeffrey Olick argues that ‘much of the state-sponsored memory in the Federal Republic of Germany has been organized as an effort to deny collective guilt’ (p. 29). The book is structured around the presentation of three succeeding ‘legitimation profiles’ – each confronting the problem of collective guilt in singular ways.

The first one, the ‘reliable nation’, which was centered on institutional reform, rather than symbolic gesture, aimed to prove that the newfound German state was a trustworthy and responsible member of the international community. During this time, the country’ s leaders draw a clear line separating the criminal Nazi leadership from the general German population. The Nazis had committed crimes ‘in the name of the German people’, as chancellor Adenauer put it in the1950s.

The ‘moral nation’ emerges in the mid-1960s with the coming of age of a second generation that was not burdened directly by the Nazi period and who could more easily pose questions regarding individual culpability and collective responsibility of their elders. The duty of remembrance was stressed now and this meant properly confronting the looming legacies of that past in the present, a past repressed and not yet ‘worked through’.

In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s German leaders sought to become a ‘normal nation’ and invested in altering the image of a past, where Nazism appeared to be spoiling the nation’ s identity for perpetuity. Normalization meant reframing and relativizing: (a) other nations also had trouble with their pasts and (b) there was more to German history than the crimes of Hitler.

From the analysis that follows, Olick asserts that when the acknowledgment of guilt comes to the foreground of German history politics it is, necessarily, at the expense of national identity. The progressives, argues Olick, seek guilt without identity, while the conservatives claim an identity without guilt (p. 32). This leaves the reader with the stirring question behind this study: a criminal past, when acknowledged, poses a legitimation dilemma and thus Germany embodies the quintessential collective memory problem.

Guilt as Identity?

The book’s epilogue makes a necessary incursion into the post-unification memory debates. Still, the reader remains somewhat unapprised of how the developments in the last 25 years in Germany fit within the overall analytical framework. Have new legitimation profiles emerged? Is the irreducible tension between guilt and identity still pertinent in the unified Berlin Republic?

The chronic weakness of identity of the Germans, to the extent that their past cannot be integrated into a stable and positive self-image (a recurrent trope from the Historians’ debate in the 1980s), has given way to rather new formulations. Authors such as sociologist Darious Zifonun have argued that the Holocaust has shifted from a burden to an opportunity, paradoxically, for a redefined national identity – one which showcases a moral transformation. This discourse is not deepening a cleavage with conservative mainstream forces in society but functions transversely as a productive source of identity formation. This poses questions regarding the linkage between remembrance (of atrocious misdeeds) and national identity, which Jeffrey Olick sees as an irreconcilable legitimation problem.

One might also inquire into its broader political implications. Which is the collectivity whose identity is being built through remembrance? Germans here can only be those who identify as descendants of a perpetrator generation and accept, as Zifonun argues, the guilt of Germans as representatives of the collectivity. These are, ironically, necessarily ethnic Germans. In this respect, we see also the limitations and potential drawbacks of state-sponsored (national) remembrance of an ethnic crime (as any genocide is) in a society where citizenship is no longer defined in ethnic or national terms. How do such mnemonic practices concern those in Germany (immigrants, refugees, and also descendants of the persecuted) whose ‘fathers’ were not part of the Holocaust?

A Method for Studying Public Memory

Jeffrey Olick’s ‘historical sociology of mnemonic practices’ (or, more simply, the historical study of commemorations and images of the past) has for some time now provided conceptual clarity and very helpful analytical tools for examining the elusive workings of collective memory. To that end, Olick has also revisited theoretical traditions in a very fruitful fashion and The sins of the fathers is possibly the most refined outcome in this line of scholarship.

Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin and the notion of dialogue and on Bourdieu’ s field theory, Olick departs from reified conceptions of collective memory and places the emphasis on practices and processes. Official representations of the past are not mere emanations of structural factors – or epiphenomena. While official memories are influenced or constrained by broader social trends and governmental agendas, they are also structuring, i.e. affecting what the state does and conditioning ensuing discursive constellations, implying both speech and actions. The productive notion of ‘memory of memory’ illustrates the dialogical approach. Earlier images of the past shape later ones, singular commemorative events being ‘always but moments in continually unfolding stories’ (p. 4).

The Sins of the Fathers: Germany, Memory, Method skillfully combines empirical exploration, historical and political erudition, and theoretical and methodical insight. For scholars and students in memory studies, this book is an excellent illustration of what rigorous and creative social memory research can look like.

* The full review of the book can be found in the European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, Volume 4, 2017 – Issue 4, pages 494-497.

Alejandro Baer is Associate Professor of Sociology and Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota.

Juan E. Méndez, a native of Argentina, is a Professor of Human Rights Law in Residence at the American University – Washington College of Law, where he is Faculty Director of the Anti-Torture Initiative. In February 2017, he was named a member of the Selection Committee to appoint magistrates of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and members of the Truth Commission set up as part of the Colombian Peace Accords. He has previously held positions as UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, an advisor on crime prevention to the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court, Co-Chair of the Human Rights Institute of the International Bar Association, President of the International Center for Transitional Justice, and the Special Advisor to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan on the Prevention of Genocide.

Juan E. Méndez, a native of Argentina, is a Professor of Human Rights Law in Residence at the American University – Washington College of Law, where he is Faculty Director of the Anti-Torture Initiative. In February 2017, he was named a member of the Selection Committee to appoint magistrates of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and members of the Truth Commission set up as part of the Colombian Peace Accords. He has previously held positions as UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, an advisor on crime prevention to the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court, Co-Chair of the Human Rights Institute of the International Bar Association, President of the International Center for Transitional Justice, and the Special Advisor to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan on the Prevention of Genocide.

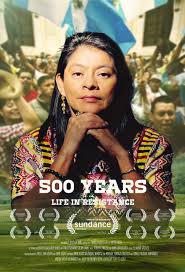

500 Years concludes with a fitting scene of young Maya girls honoring the dead on All Saints Day, when giant colorful kites are weaved and flown to celebrate ancestors across the skies of Guatemala. The beauty and power of the metaphor speaks for itself, as the girls attempt twice unsuccessfully before their kite ultimately soars – seeming effortlessly, forever majestically – in playful circles that tease the sun.

500 Years concludes with a fitting scene of young Maya girls honoring the dead on All Saints Day, when giant colorful kites are weaved and flown to celebrate ancestors across the skies of Guatemala. The beauty and power of the metaphor speaks for itself, as the girls attempt twice unsuccessfully before their kite ultimately soars – seeming effortlessly, forever majestically – in playful circles that tease the sun.

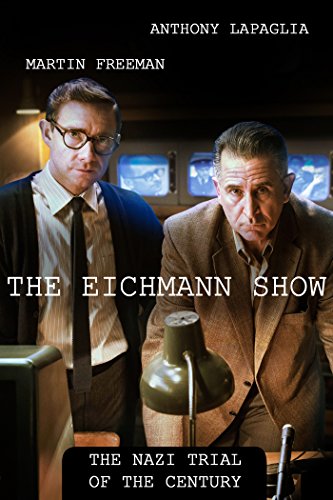

As we watch neo-Nazis and white supremacists on our TV’s and in our news feeds it might be a good time to reacquaint ourselves with the original Nazis and just what happens when we remain silent. On Netflix, we can watch

As we watch neo-Nazis and white supremacists on our TV’s and in our news feeds it might be a good time to reacquaint ourselves with the original Nazis and just what happens when we remain silent. On Netflix, we can watch  Also on Netflix is,

Also on Netflix is,