“Zooming in” is clearly trending in the field of Holocaust research. Since the onset of the new millennium, scholars have increasingly favored a narrower perspective. The number of sound biographies and prosopographies of “ordinary” men (and women) is growing, as is that of studies on the impact of the Holocaust on local communities. Moreover, the “spatial turn” in Holocaust studies is leading to important new research projects, such as those by Tim Cole, Albert Giordano, and Anne Kelly Knowles, that explore the use of geography for Holocaust studies and further narrow down the scope of research—to a city, a ghetto, a single building block, or a concentration camp.

Many of these recently published studies of applied scale-reduction are not simply examples of traditional local history or traditional biographies. They are “microstudies,” that is, small-scale studies of a specific place, of people in that place, and of their relations and encounters in their everyday lives. More than four decades after Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg published his The Cheese and the Worms (1976, Italian; 1980, English), microhistory has clearly made its entry into the field of Holocaust studies, yet it is remarkable how few of these new microstudies are conceptualized as such. How can microhistory aid in our understanding of the Holocaust? How should we define its methods of research and its rules for data collection and interpretation? How do we deal with the issue of subjective individual experiences? To what extent do our sensibilities as researchers affect the exploration of individuals and their particular stories, rather than the general historical events? Most scholars agree that macroprocesses translate into experiences on the microlevel. There is also general agreement that studying the Holocaust from a grassroots perspective may be beneficial to our knowledge of the Holocaust. Yet reflection on microhistory as a research method or perspective is minimal, and specific questions that microhistory raises for Holocaust research are barely addressed.

It is the merit of Tal Bruttmann and Claire Zalc to bring these problems to our attention in Microhistories of the Holocaust, a volume that appeared in 2016. Both editors are historians with a long track record in microhistorical research of the Holocaust in France. In their introduction they argue that their volume is meant to show the historiographical implications and relevance of the “microhistorical turn” for the field of Holocaust studies. According to Bruttmann and Zalc, microhistory is about changing the scale of analysis and, by doing so, laying bare the complexity and diversity of the Holocaust. What it all comes down to is “deconstruction” of monolithic explanations and “distortion” of the grand narrative.

It is the merit of Tal Bruttmann and Claire Zalc to bring these problems to our attention in Microhistories of the Holocaust, a volume that appeared in 2016. Both editors are historians with a long track record in microhistorical research of the Holocaust in France. In their introduction they argue that their volume is meant to show the historiographical implications and relevance of the “microhistorical turn” for the field of Holocaust studies. According to Bruttmann and Zalc, microhistory is about changing the scale of analysis and, by doing so, laying bare the complexity and diversity of the Holocaust. What it all comes down to is “deconstruction” of monolithic explanations and “distortion” of the grand narrative.

This, however, does not always come across in the essays by the contributing authors. Writing on Jewish reactions to the Holocaust in various German cities (and Vienna), Wolf Gruner, for example, asserts that his work should be seen as complementary and enriching (p. 211): in their contribution Tim Cole and Alberto Giordano cautiously state that their study of the ghetto of Budapest challenges the general idea that ghettoization was all about physical segregation (p. 114). These two case studies (and, for that matter, all seventeen case studies collected in this volume) refine our image of the Holocaust: they are more about the condensing and sharpening of the pixels than about deconstructing the larger picture.

The volume is composed of three parts, each organized around one theme: 1) the scales of analysis; 2) victims and perpetrators; and 3) sources between testimonies and archives. A closer look at the individual contributions indicates that this division is far from watertight as nearly all of the contributions touch, more or less explicitly, upon the three themes and the volume could thus easily have been ordered differently. The highly interesting study of Nicolas Mariot and Claire Zalc, on persecution trajectories of Jews from the French city of Lens, for example, is much more about methodology and the integration of quantitative analysis in a microhistorical study—and thus on sources—than on scales of analysis. The same is true for other contributions, such as that by Jan Grabowski on the complicity of Polish gentiles during the Holocaust.

In spite of this, the individual contributions are well worth reading and together they are a clear indication of the broad spectrum and variety of microhistorical approaches. Some of the contributors concentrate on the category of victims and paint intimate portraits of individual Jews (Christoph Kreutzmüller, for example, on the escape of the Jewish German Richard Frank) or Jewish families and their rescue networks (Nicolas Mariot and Claire Zalc, on the French Dawidowicz family, but also Melissa Jane Taylor, on the Austrian Katz family). Others, like Leon Saltiel, Jeffrey Wallen, Tim Cole, and Alberto Giordano, choose a well-defined place in time and space and meticulously analyze how relations between Jews and non-Jews evolved in or around these places (the Jewish cemetery in Thessaloniki, the ghetto of Budapest, the city of Christianstadt). Again others, like Tal Bruttmann, Markus Roth, Jan Grabowski, Thomas Frydel, Vladimir Solonari, and Alexandru Muraru, look at bleaker moments in these relations: their contributions tell the story of local gentiles turning into looters, extorters, and murderers of their Jewish neighbors—in France, Poland, Transnistria, and Romania.

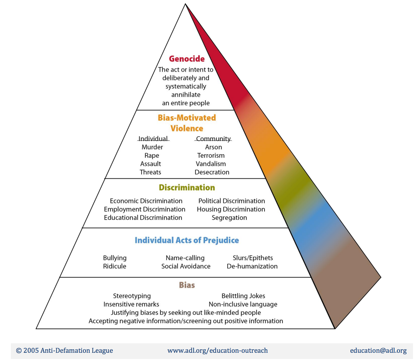

Crisscrossing the map of Nazi Europe, this volume presents a kaleidoscopic view of the Holocaust and, more specifically, of individual reactions to persecution and genocide. The contributions underline the extra value of microhistory, particularly for the study of relations and interactions between Jews and their non-Jewish fellow citizens. More generally, the volume demonstrates that the traditional tripartite division into victims, perpetrators, and bystanders is at least questionable. In most of the presented microstudies bystanders are absent, if not nonexistent.

As a final note, a concluding chapter by the editors would have been welcome: for conclusions and comparisons, but also for dealing with larger, paradigmatic questions related to the genre of microhistory. How do we get from the singular case to the broader picture? In other words, how do we connect a microcase to macrocontext? Answering these and similar questions was not in the purview of this volume, however. The editors’ main aim was to show through their collection of microstudies the complexity and diversity of the Holocaust. In this, they have succeeded admirably.

*This review was originally published on H-Genocide.

Geraldien von Frijtag. Review of Zalc, Claire; Bruttmann, Tal, eds., Microhistories of the Holocaust. H-Genocide, H-Net Reviews. February, 2018. URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=50222

Geraldien von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel is Associate Professor at the Department of Political History, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. She has published widely on WWII, the Holocaust and Dutch reactions to Nazi occupation policy. She is this year’s senior fellow in residence of the USC Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research, Los Angeles.

As a middle and high school history and social studies teacher, I have taught about the Holocaust and other genocides for many years. At the beginning of my career, students in my classes would have encountered only the Holocaust, but, recently, I have broadened my curriculum to include many additional examples and aspects of genocide. Despite growing

As a middle and high school history and social studies teacher, I have taught about the Holocaust and other genocides for many years. At the beginning of my career, students in my classes would have encountered only the Holocaust, but, recently, I have broadened my curriculum to include many additional examples and aspects of genocide. Despite growing