Chad Alan Goldberg is Professor of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin Madison. His interests lie in the sociology of citizenship, including the development of rights and duties over time, changing levels and forms of democratic participation and shifting patterns of civil inclusion and exclusion. He is the author of Citizens and Paupers: Relief, Rights, and Race, from the Freedmen’s Bureau to Workfare. His most recent book, Modernity and the Jews in Western Social Thought examines how Jews became a touchstone for defining modernity and national identity in French, German, and American social thought from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries.

Alejandro Baer: Your book highlights how for classical theorists, such as Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx or Robert Park, Jews became reference points for the interpretation of the new modern social order. Why do Jews occupy this singular space in the theorizing of modernity?

Chad Goldberg: To answer to this question, some people have pointed to the Jewish backgrounds of authors like Durkheim, Marx, Simmel, and Wirth. Others have suggested that the answer lies in the distinctive social positions that Jews occupied. There may be some truth to both views. Durkheim’s thinking, for example, was surely directed against the antisemitism of his milieu, and it’s true that German Jews were disproportionately engaged in commerce and more urbanized than the general population. But my book suggests another way to answer this question; I draw on the work of Lévi-Strauss to develop a relational (or, as others might say, structuralist) explanation.

Chad Goldberg: To answer to this question, some people have pointed to the Jewish backgrounds of authors like Durkheim, Marx, Simmel, and Wirth. Others have suggested that the answer lies in the distinctive social positions that Jews occupied. There may be some truth to both views. Durkheim’s thinking, for example, was surely directed against the antisemitism of his milieu, and it’s true that German Jews were disproportionately engaged in commerce and more urbanized than the general population. But my book suggests another way to answer this question; I draw on the work of Lévi-Strauss to develop a relational (or, as others might say, structuralist) explanation.

Can you explain?

Lévi-Strauss argued that the choice of animals in a totemic system was neither arbitrary nor based on a “natural stimulus.” Rather, it was how animals contrasted to each other that made them meaningful. These relationships among animals formed a kind of code for signifying kinship relations, but the code rested on resemblances between different relationships, not one-to-one correspondences between the things in those relationships. As Lévi-Strauss put it, it is not that an animal and a kinship group resemble each other; rather, there are “animals which differ from each other,” and there are human beings “who also differ from each other,” and “the resemblance presupposed by so-called totemic representations is between these two systems of difference.” So, there is no reason to expect a direct relation between a bear totem and a bear clan; the clansmen aren’t necessarily ursine or dependent on bears. But when the bear totem is contrasted to the eagle totem of another clan, the relationship between animals might resemble the kinship relation: bear is to eagle as bear clan is to eagle clan. “Natural species are chosen” to be totemic emblems, Lévi-Strauss famously concluded, “not because they are ‘good to eat’ but because they are ‘good to think.’”

So Jews are “good to think,” too?

Yes, they have been good to think in a similar way. When Jews and Christians distinguished themselves from each other in the first centuries of the Common Era, they produced two opposed but related categories. Likewise, when European thinkers began to distinguish their own era as qualitatively different from the past, they produced two opposing terms, the premodern and the modern. It’s not far fetched to think of the relationship between Jews and Christians as a code for signifying the relationship between the premodern and the modern.

In your book, you distinguish between German, French and American traditions in their conceptualization of Jews and modernity. What are the main differences?

I borrowed the idea of national sociological traditions from Donald Levine. He tried to show that French, German, and American scholars developed the theoretical underpinnings of sociology in different ways, rooted in different religious and philosophical heritages. That notion can be overstated, but it’s not untrue, and I was interested in how these national differences might shape thinking about Jews and modernity. I also organized my book in terms of different root metaphors (or more precisely synecdoches) for modernity. Social thinkers have sometimes singled out a master process that they believe captures or explains the central tendencies of modern society. A part of modern society is thereby made to represent the whole. Fred Matthews has suggested that liberal thinkers in the United States tended to ascribe to the city or to immigration the problems and tensions that Europeans blamed on democracy or industrial capitalism. Again, this idea can be easily overstated, but it’s useful for analytical purposes. As an analytical choice, I focused on different metaphors within different national traditions: democracy in the French tradition, capitalism in the German tradition, the city in the American tradition.

These differences were sometimes consequential. It’s striking, for instance, how German ideas were creatively reoriented and transformed through their transposition to the American context and by the influence of American pragmatism. Robert Park and his students explicitly drew on Werner Sombart’s work, but they gave his sinister description of Jews as nomads and disorganizers a potentially positive interpretation, because in their view, it was only out of such activity that a new, freer, more rational, and wider community could arise. What appeared in Sombart’s work as an alienating and destructive figure was recast by Park as emancipating and potentially constructive.

But there are also important continuities across national traditions and metaphors for modernity. Although the authors I examine worked in different national traditions and emphasized different features of modern society, they all invoked Jews as a touchstone for defining modernity and national identity in a context of rapid social change.

Does “antisemitism”, as a term and field of study, illuminate or rather obscure your thesis? You state that to confer symbolic centrality to Jews is not always antisemitic.

Conferring symbolic centrality to Jews is always dangerous, because it renders Jews potential targets in ongoing conflicts in which they may have little real involvement or influence, but I don’t think it’s always antisemitic. After all, religious Jews confer centrality upon themselves when they emphasize their special responsibility for tikkun olam.

I would say that my book draws on the sociology of antisemitism and tries to situate it in a broader analytical framework. When we ask what Jews signified to French, German, and American social thinkers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and how they described Jews in relation to their own wider societies, we can locate the possible answers along two major axes: temporal (Jews are advanced or backward) and evaluative (Jews are good or bad). Negative images of Jews as a threatening avant-garde or a stubbornly backward people that refuse to exit the historical stage have been major elements in antisemitism since at least the nineteenth century. But the sociology of antisemitism deals primarily with the evaluative axis that I described, and it tends to neglect positive depictions of Jews. What I am suggesting, then, is that the sociology of antisemitism, while necessary and valuable, needs to be situated within a broader sociology of collective representations that encompasses both negative and positive representations of Jews, and the temporal as well as evaluative axis of representation.

You claim that post-colonial theory has shown a very limited understanding of antisemitism, basically seeing only the reactionary aspect of it, as another form of racism and ignoring that Jews were also identified as ultra-modern and cosmopolitan. How do you explain this conceptual blind spot?

Perhaps part of the reason for this blind spot is the ambition of post-colonialist theory to illuminate all forms of cultural domination through the experience of colonial subjects. Post-colonial theory illuminates a lot, but it doesn’t illuminate everything fully or equally well. Zygmunt Bauman suggested that attitudes toward Jews are not so much heterophobic (resentful of the different) as proteophobic, which is to say, apprehensive about whatever “does not fit the structure of the orderly world, does not fall easily into any of the established categories.” If he’s right—and I think he is—then antisemitism is not merely another kind of racism or colonialism; it has specific and distinctive features that need to be grasped.

One could consider this misunderstanding of the nature of antisemitism as being at the root of the debates between Holocaust Studies and Genocide Studies, the latter seeing often Nazism as a colonial project or Jews as “colonized populations.”

Yes, it seems to me that the post-colonial perspective on antisemitism is another instance of a more general phenomenon, namely, recurring efforts to squeeze Jews, in a Procrustean fashion, into categories that do not easily fit. Similar dynamics may be discernible in the debates between Holocaust Studies and Genocide Studies.

How does radical anti-Zionism fit in your model? Would this resemble the classical radical critique of Jewish particularism, i.e. Jews threatening liberating advances of society?

Contemporary anti-Zionism signifies to me the demonization of Israel in a selective, one-sided, essentialist, or paranoid fashion, or the demand for its outright elimination. I think it’s necessary to distinguish anti-Zionism in this sense from criticism of Israel, its human rights violations, or the policies of its successive governments, just as one can distinguish anti-Americanism from criticism of the United States or political opposition to U.S. policies. I think it’s also necessary to distinguish anti-Zionism analytically from antisemitism, though they overlap in practice, and there are important analogies between the two ideological formations.

My book concludes that the history it covers extends into the present with the Jews—and now the Jewish state—continuing to serve as a touchstone for defining the meaning of European or American modernity in the twenty-first century. In fact, that continuity was one of the things that inspired me to write the book. It seemed to me that longstanding habits of thought continued to reappear in contemporary discussions about Jews and Israel, often without much historical awareness on the part of the people who articulated them, and that troubled me.

So we are still hearing Clermont‑Tonnerre, who claimed that one had to refuse everything to the Jews as a nation and accord them everything as individuals?

Yes, insofar as Jewish nationalism is seen as retrograde. The last chapter of my book describes how the old opposition between “backward” Jewish particularism and “progressive” Christian universalism is pressed into service by contemporary social thinkers for new political projects. You see this in the work of prominent intellectuals like Alain Badiou and Enzo Traverso, for whom the Jews, “Zionists,” or the Jewish state appear as an obstacle to modern progress.

In that chapter, you also challenge a frequently invoked claim that Muslim immigrants have become “the new Jews” and that the Jewish question in Europe has largely been solved. Where do you see the shortcomings of those analogies?

At a high enough level of abstraction, the experiences of Jews and Muslims in the West can be seen as variations on a common process of civil incorporation. When viewed in those terms, the historical experiences of Jews and the contemporary experiences of Muslims in Western Europe are analogous. But it’s important to remember that analogies, properly used, allow us to identify differences as well as similarities between cases. When the analogy between Jews and Muslims is examined at a more concrete level, we find three important differences. First, comparisons of Jews and Muslims tend to overlook significant differences in the socio-historical contexts of their incorporation. These differences include the relative size, type of “strangeness,” and socioeconomic status of each out-group, as well as the presence or absence of religiously inspired political violence. Second, analogies between Muslims and Jews neglect important differences in the discursive representation of the two out-groups. Both groups have been portrayed as personifications of a backward Orient, but only Jews have also and in addition figured prominently in modern social thought as agents of Western modernity. Third, while Muslims have surely emerged as an important touchstone in their own right for defining the meaning of European or American modernity, they have not displaced Jews in this respect. As we’ve discussed already, the Jews—and now the Jewish state—continue to serve as an important reference point. While some contemporary intellectuals suggest that the previously outcast Jews have now become privileged insiders of a dominant Judeo-Christian, European, or Western order at the expense of Muslims, those claims fail to recognize how the positive image of a modern, postnational Europe is constructed in opposition not only to the Muslim other but also to the Jewish state.

At a high enough level of abstraction, the experiences of Jews and Muslims in the West can be seen as variations on a common process of civil incorporation. When viewed in those terms, the historical experiences of Jews and the contemporary experiences of Muslims in Western Europe are analogous. But it’s important to remember that analogies, properly used, allow us to identify differences as well as similarities between cases. When the analogy between Jews and Muslims is examined at a more concrete level, we find three important differences. First, comparisons of Jews and Muslims tend to overlook significant differences in the socio-historical contexts of their incorporation. These differences include the relative size, type of “strangeness,” and socioeconomic status of each out-group, as well as the presence or absence of religiously inspired political violence. Second, analogies between Muslims and Jews neglect important differences in the discursive representation of the two out-groups. Both groups have been portrayed as personifications of a backward Orient, but only Jews have also and in addition figured prominently in modern social thought as agents of Western modernity. Third, while Muslims have surely emerged as an important touchstone in their own right for defining the meaning of European or American modernity, they have not displaced Jews in this respect. As we’ve discussed already, the Jews—and now the Jewish state—continue to serve as an important reference point. While some contemporary intellectuals suggest that the previously outcast Jews have now become privileged insiders of a dominant Judeo-Christian, European, or Western order at the expense of Muslims, those claims fail to recognize how the positive image of a modern, postnational Europe is constructed in opposition not only to the Muslim other but also to the Jewish state.

Do you think that your own discipline of sociology sufficiently comprehends the centrality of Jews and Judaism as reference points for thinking modernity?

No. Classical sociology devoted considerable attention to Jews and Judaism—in that sense, Jews were highly visible—but there is little reflection among contemporary sociologists about the meaning or significance of those references. There is little understanding of the significance of the Jewish question to the origins and development of the discipline. And there is little or no understanding that the theoretical dualisms which are so central to sociology are based in part on the historical opposition between Jews and gentiles. I hope my book will deepen and improve comprehension of these things among sociologists and others.

Alejandro Baer is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota and the Stephen C. Feinstein Chair in Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Fern and her late husband Bernard established the Badzin Fellowship in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, which has supported for the last decade graduate students in the College of Liberal Arts committed to research in the field. Bernard and Fern also created the Badzin Lecture Series fund, helping to bring renowned experts to campus.

Fern and her late husband Bernard established the Badzin Fellowship in Holocaust and Genocide Studies, which has supported for the last decade graduate students in the College of Liberal Arts committed to research in the field. Bernard and Fern also created the Badzin Lecture Series fund, helping to bring renowned experts to campus.

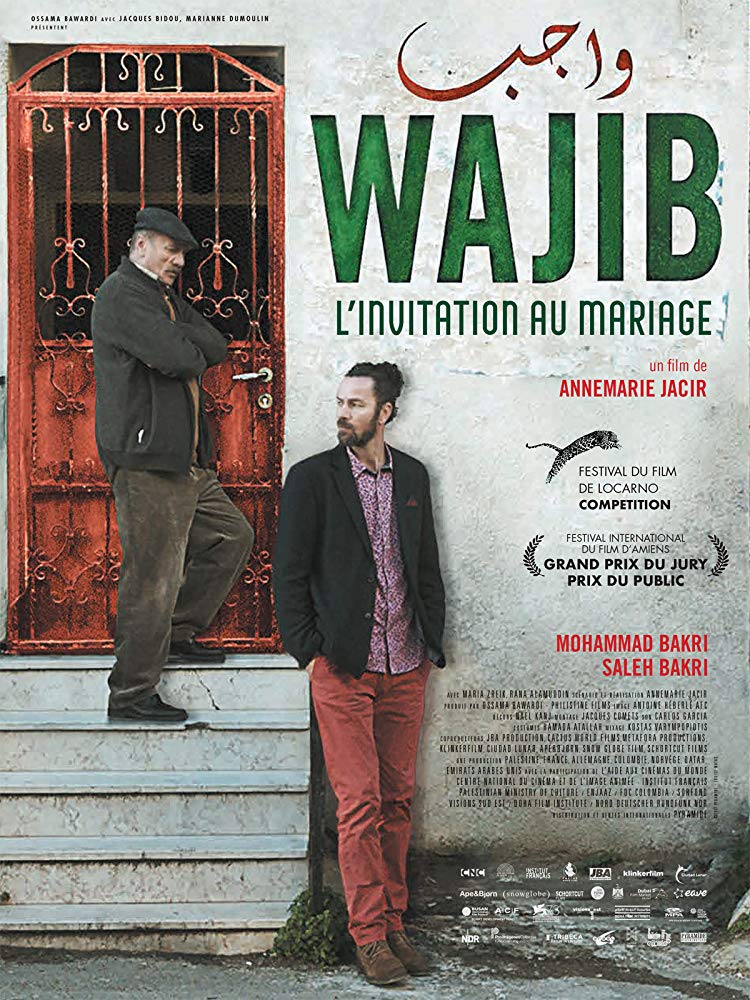

Experimental Narrative / 77 minutes / 2017

Experimental Narrative / 77 minutes / 2017

After informing on her Islamist brother, Samia (Sarra Hannachi) seeks refuge by illegally immigrating to France just after Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution. With no friends, no family, and no papers, Samia adapts to life in a foreign land. She meets a young man, Imed (Salim Kechiouche); finds work as an assistant to the elegant but mysterious Leila (Hiam Abbass); and is quickly enmeshed in a web of sexual tension. A timely narrative, Foreign Body transcends the media’s typical reductive narratives of forced migration and desperation through close, handheld camera work and abstract insights into the story of a young woman.

After informing on her Islamist brother, Samia (Sarra Hannachi) seeks refuge by illegally immigrating to France just after Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution. With no friends, no family, and no papers, Samia adapts to life in a foreign land. She meets a young man, Imed (Salim Kechiouche); finds work as an assistant to the elegant but mysterious Leila (Hiam Abbass); and is quickly enmeshed in a web of sexual tension. A timely narrative, Foreign Body transcends the media’s typical reductive narratives of forced migration and desperation through close, handheld camera work and abstract insights into the story of a young woman. Narrative Short | 15 minutes | 2017

Narrative Short | 15 minutes | 2017

Set in Damascus in the spring of 2011, amidst the rumblings of revolution, this complex narrative takes on issues of sexuality and gender inequality. Nahla (Manal Issa) explores her own sexual desires and navigates the social norms that structure women’s roles in society. Meanwhile, the Syrian revolution gains momentum and the state’s severe response engulfs the country in war. Against this violent backdrop, Nahla focuses on emigration and her arranged marriage to Syrian American Samir (Saad Lostan). But when Samir chooses her younger sister (Mariah Tannoury), Nahla grows closer to her new neighbor, who has just moved into her building and opened a brothel in the apartment upstairs. As Nahla plays out her fantasies in dreams and reality, the film critiques gender stereotypes, providing a unique metaphor for Syria’s increasing instability.

Set in Damascus in the spring of 2011, amidst the rumblings of revolution, this complex narrative takes on issues of sexuality and gender inequality. Nahla (Manal Issa) explores her own sexual desires and navigates the social norms that structure women’s roles in society. Meanwhile, the Syrian revolution gains momentum and the state’s severe response engulfs the country in war. Against this violent backdrop, Nahla focuses on emigration and her arranged marriage to Syrian American Samir (Saad Lostan). But when Samir chooses her younger sister (Mariah Tannoury), Nahla grows closer to her new neighbor, who has just moved into her building and opened a brothel in the apartment upstairs. As Nahla plays out her fantasies in dreams and reality, the film critiques gender stereotypes, providing a unique metaphor for Syria’s increasing instability.