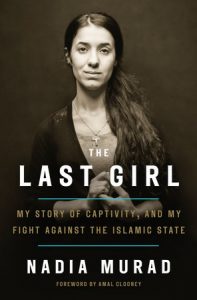

Nadia dreamed of either becoming a history teacher or opening a hair salon in Kocho, Iraq – a small village of farmers and shepherds in southern Sinjar. In her book, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State (2017), Nadia talks about growing up with her many brothers and sisters amidst a tight-knit Yazidi community. Central to Yazidi identity is the history of the seventy-three past firmans (to mean genocide) committed against the community by outside forces. Nadia, along with others Yazidis, learned about this history but never thought she herself would soon survive a genocide against her own religious community. Nadia writes, “…these stories of persecution were so intertwined with who we were that they might as well have been holy stories. I knew that the religion lived in the men and women who had been born to preserve it, and that I was one of them.” To Nadia, however, the previous genocides belonged to a distant past. The ongoing violence in Iraq and neighboring Syria also did not feel like part of the contemporary plight of Yazidis – until one day ISIS began to surround Kocho and the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga forces fled, leaving them unprotected.

Nadia dreamed of either becoming a history teacher or opening a hair salon in Kocho, Iraq – a small village of farmers and shepherds in southern Sinjar. In her book, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State (2017), Nadia talks about growing up with her many brothers and sisters amidst a tight-knit Yazidi community. Central to Yazidi identity is the history of the seventy-three past firmans (to mean genocide) committed against the community by outside forces. Nadia, along with others Yazidis, learned about this history but never thought she herself would soon survive a genocide against her own religious community. Nadia writes, “…these stories of persecution were so intertwined with who we were that they might as well have been holy stories. I knew that the religion lived in the men and women who had been born to preserve it, and that I was one of them.” To Nadia, however, the previous genocides belonged to a distant past. The ongoing violence in Iraq and neighboring Syria also did not feel like part of the contemporary plight of Yazidis – until one day ISIS began to surround Kocho and the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga forces fled, leaving them unprotected.

On August 3rd, 2014, ISIS besieged Kocho. Within two weeks, ISIS ordered villagers to congregate in the local schoolyard, giving the local mukhtar (chief) an option to determine whether the community would convert to Islam. Upon his refusal, all the men were driven to a nearby site to be executed. Boys were abducted for indoctrination in ISIS training camps, women and girls were forced into ISIS’ sex slave trade, and elderly women deemed not fit for the trade were executed. Nadia was held in brutal captivity, where she was repeatedly raped and beaten, sold and resold to various militants, and forcibly converted to Islam. The first time Nadia tried to escape, she was gang raped as punishment. The second time she was presented with an opportunity to flee, she fearfully walked out of the unlocked front door into the streets of Mosul and the dark of the night. Realizing she must seek shelter, she knocked on the door of a random house. Luckily, a Sunni family greeted her, agreed to take her in, and even helped smuggle her into Kurdistan. While she feels immense gratitude and recognizes the sacrifices of the family that helped her, she also felt betrayed by the thousands of Sunni families who remained bystanders, and sometimes even joined ISIS in the genocidal campaign against the Yazidis.

Once she escaped, Nadia made her way to a refugee camp and was reunited with the surviving members of her family and community. Soon after, she moved to Germany as part of a refugee program to work with Yazidi survivors of the genocide. Nadia details the pain and difficulty of dealing with trauma and loss amongst a tight-knit religious minority community. In her quest to find some healing, she calls for justice. Nadia has partnered with lawyer Amal Clooney and the Yazda organization to document the massacres against the Yazidis and to bring ISIS militants to justice for war crimes and genocide. Nadia writes, “Sometimes it can feel like all that anyone is interested in when it comes to the genocide is the sexual abuse of Yazidi girls…I want to talk about everything – the murder of my brothers, the disappearance of my mother, the brainwashing of the boys – not just the rape.” The United Nations has officially declared the violence against the Yazidis as genocide, and the UN Security council has created a task force to gather evidence of these atrocities.

“Attacking Kocho and taking girls to use as sex slaves wasn’t a spontaneous decision,” Nadia writes. ISIS considers Yazidis to be kuffar (infidels) and have given them the option of conversion, sex slavery, or death, unlike other religious communities, such as Christians, who could pay jizya (taxes) and remain Christians under ISIS rule. The withdrawal of the peshmerga with no warning and the complicity of some Sunnis exacerbated the distrust between Yazidis and Arabs, as well as some Kurds. Thus, any attempt at reconciliation will be an incredibly difficult task. Nadia concludes the book with a call for action directed to world leaders – particularly Muslim religious leaders – to protect the oppressed, demanding that she be “the last girl in the world with a story like” hers.

Miray Philips is a Ph.D. graduate student in Sociology with a focus on narratives of violence and suffering, collective memory and identity in response to conflict in the Middle East and North Africa. Miray was the 2016-17 Badzin Fellow.

Comments