Was Hitler a bully? Evan Selinger, professor of philosophy at the Rochester Institute of Technology, shared in an essay in Slate how his 5-year-old daughter’s teacher compared the “worst criminal in history to a playground tormentor.” Perhaps an extreme example. Yet to understand this increasingly common trend to educate students about “Bully Hitler,” one must recognize two developments that are currently shaping the way teachers, curriculum writers, and educational institutions in the United States are educating young people about the Holocaust. First, there is a universalization of the Holocaust in an attempt to make its study relevant to students’ lived experiences and to provide them with overt moral and ethical lessons in the form of social-emotional and character education. Second, increasingly, many state legislatures have mandated Holocaust education, often suggesting a study in the form of character education to younger students, some as young as elementary school (5-10 years old). New Jersey’s Commission on Holocaust Education, the entity responsible for ensuring schools meet the state’s Holocaust-education mandate, reminds educators that, “the law indicates that issues of bias, prejudice and bigotry, including bullying through the teaching of the Holocaust and genocide, shall be included for all children from K-12th grade.” Thus, increasingly, students are taught to link the Holocaust with bullying and pushed to contemplate the choices they might have made during the Holocaust, as well as the choices they might make in their school’s cafeterias, hallways, and playgrounds as bullies, bystanders, or upstanders.

With Holocaust educational mandates, like those in New Jersey, the question of whether or not five-year-olds should learn about the Holocaust has become instead, how should we teach five-year-olds about the Holocaust? Following such a shift, bullying becomes a popular, relatable metaphor, serving the dual purpose of meeting mandates and educating students about bullying (also increasingly mandated by state law). Some educators, such as Harriet Sepinwall, a professor of education and Holocaust studies, contend that young students “became more empathetic, more accepting of diversity, and more willing to act when someone was being treated unfairly, as a result of learning about the Holocaust.” Such approaches have been called into question as serving neither the objectives nor imperatives of educating students about the Holocaust. Samuel Totten, a scholar of genocide education, voicing objections to these trends, claims that Holocaust education “when applied to the teaching of very young children […] implies nothing more than an attempt to develop personal qualities like tolerance and respect for difference […] It does not involve teaching the history of the Holocaust per se.” Indeed, critics of such social-emotional approaches often focus on the de-historicization and de-contextualization of Holocaust narratives in American schools.

Barbara Coloroso, an expert in student behavior and issues of bullying, has drawn perhaps the clearest connections between bullying and genocide. In her book, Extraordinary Evil: A Brief History of Genocide, Coloroso writes: “It [genocide] is the most extreme form of bullying – a far too common behavior that is learned in childhood and rooted in contempt for another human being who has been deemed to be, by the bully and his or her accomplices, worthless, inferior, and undeserving of respect. The progression from taunting to hacking a child to death is not a great leap but actually a short walk.” Coloroso’s work has been criticized for constructing an overly simplistic (de-historicized) view of genocide, yet others have praised the work, suggesting it for parents and educators wishing to teach young people about bullying.

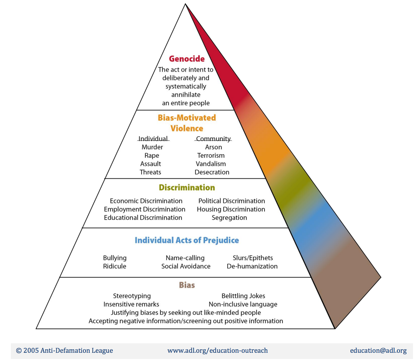

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) has also drawn connections between bullying and the Holocaust and genocide. The ADL’s Pyramid of Hate places bullying within a tiered framework of escalating behaviors that could, if left unchecked, ultimately lead to genocide. One student, reflecting on their experiences learning about the Holocaust, described their understanding of the connections between bullying and the Holocaust in a college-entrance essay: “The Pyramid of Hate starts on the bottom with non-inclusive phrases and jokes and escalates into more serious acts of hate like violence and can eventually lead to genocide or total annihilation of a kind of people, which is what happened in the Holocaust. Hitler and his followers created a genocide of the Jews and Gypsies in Europe. I never before connected phrases like, “that’s gay” to genocide, but now I can’t forget how one leads to the other.” Such statements, while highlighting the result of trends towards a de-historicization and de-contextualization of the Holocaust, reflect what many parents and educators would express as desirable outcomes of Holocaust education, such as tolerance for difference and awareness of prejudice.

Critics have also questioned the coupling of the Holocaust and anti-bullying lessons as not effectively addressing schoolyard bullying. School psychologist and bullying expert Izzy Kalman contends that such educational programs often unnecessarily exaggerate bullying for those students being bullied. He writes that the “effect of the comparison is to make children believe that being bullied is the absolutely most horrific experience imaginable.” Kalman’s rather blunt assessment of such curricula is that it catastrophizes bullying and trivializes the Holocaust.

Holocaust education has emerged as a standard in school curricula around the country. Increasingly its study, somewhat removed from the context of history (and the content of history class), has been called upon to provide new generations of students with just enough fodder to contemplate their own individual choices. What is clear, is that little research exists examining the effects of linking the Holocaust to anti-bullying in elementary and secondary curriculum, despite the growing popularity of the “Bully Hitler” metaphor.

George Dalbo is a Ph.D. student in Social Studies Education at the University of Minnesota with research interests in Holocaust, comparative genocide, and human rights education in secondary schools. Previously, he was a middle and high school social studies teacher, having taught every grade from 5th-12th in public, charter, and independent schools in Minnesota, as well as two years at an international school in Vienna, Austria.

Comments