Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey on WYPR (Baltimore’s NPR affiliate) discussing technology and the Occupy movement: Click here to listen to the audio.

Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey on WYPR (Baltimore’s NPR affiliate) discussing technology and the Occupy movement: Click here to listen to the audio.

Picture of the week comes from David Banks. FourSquare and Occupy at that critical intersection of the digital and physical.

This week at Cyborgology…

I wanted the photo above to be an example of the new so-called “living pictures” that have garnered much recent attention. However, Lytro has not provided proper embedding code so I can only post this screenshot of a living photo. I highly recommend clicking on the photo or clicking here before reading along.

Update: the code now works, so before reading on, click the photo above. Click around various parts of the image and watch the focus change.

Okay, by now you have experienced a living photo. You see it, but you can also make it come alive; touch it, change the focus, reorient what is seen and focused on. Some might even argue that you get to decide the meaning of the story the image tells. This post asks: what would it mean if we start posting living pictures across social media? Might it change how we take photos? How might we differently interact with social media photography when we can manipulate the faces of our friends and engage with the images in a new way?

It has been my contention that photography can teach us quite a bit about social media. Not just because there are so many photos online but because photography serves as a familiar and grounding reference point to the newness of social media. Photography situates the novel and sometimes disorienting ways we are documenting ourselves online with a technology that did the same offline more than a century ago.

I have written about Susan Sontag’s description of photographers being always at once poets and scribes when taking photos to describe how we create our social media profiles in a similar way. I have used the concept of the “camera eye” photographers develop to discuss how social media has imbued us with a similar “documentary vision.” I also described how the explosion of faux-vintage photos taken with Hipstamatic and Instagram serve as a powerful example of how social media has trained us to be nostalgic for the present in a grasp at authenticity.

Here, I want to discuss what many are calling “revolutionary” and the next “big thing” in photography: the so-called living pictures linked to above developed by the Lytro company that have just entered the consumer market with cameras shipping early next year.

Lytro “Living Picture” Technology

This is not an essay so much about the technology but instead the implications of how it might become manifested across social media. Indeed, this is highly speculative since consumers have not yet even used the technology. Further, I am not writing here about the potential implications of Lytro technology for professional photographers but instead how it might be used in everyday, mainstream social media environments. If writing about professional photographers, one might focus on how living pictures make explicit that all photographic images are always co-creations between photographer and audience; or how these photos also make explicit that images are never the objective capturing of reality but also a creative endeavor via what is photographed and how the image is produced. Let me pull myself away from these tangents and briefly explain what Lytro’s “living pictures” are.

Lytro is the first company to bring “light-field” technology into a small consumer device. Light-field, or “plenoptic”, camera technology captures all the light–its color, intensity and direction–that makes contact with the internal sensor. It does not select a single focus point but captures all possible focus points at once. To understand the result, one needs to know just a little about what is called “depth of field.”

The Lytro camera has a constant aperture of f/2. This is simply referring to the size of the hole through which light travels from the world into the camera. A small f number (or “f-stop”) means a wide opening and f/2 is considerably wider than what one usually finds in point-and-shoot cameras. Besides capturing more light, the wide aperture means that either that which is near the camera or that which is far away will be in focus, but certainly not both. Objects in the foreground will be in focus and the background blurry, or vice versa.

And the Lytro camera lets one choose what will be in sharp focus and what is blurry after the photo is taken. This is brand new. Tellingly, Lytro put this technology not in professional cameras but in a point-and-shoot camera priced within the grasp of a large consumer demographic. Clearly, the primary intention is to create a new “living” type of photo to post online across social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr and so on.

I will mostly skip over the stuff you might get in a consumer review of a new gadget. For instance, the editing one can do to a Lytro photograph is more limited (e.g., no faux-vintage filters, yet). The process to get the photo from the camera to Facebook is a bit awkward (from camera to a cable to a computer to Lytro’s software to Lytro’s website and then finally to Facebook) relative to a smartphone that can post non-living photos directly to various social media sites. And given that these cameras are not yet even on sale (let alone popular; I will not predict if they will be or not), there are many obstacles between now and some reality where we see lots of “living photos” in our Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr streams.

But if Lytro is successful and these self-shot living pictures do start to appear in our social media streams then we have at least the potential for a new type of a social media object. And this is why living pictures deserve conceptual attention here.

Living Pictures

The viewer of a living picture seemingly has a new sort of control with respect to the photo-object. By clicking around inside of the photo and brining things in and out of focus, others are now more active in choosing what story the photo is telling. They might feel that their own perspective, taste and aesthetics can now determine what they ultimately see. Further, the experience might be more intimate because rather than just seeing a friend’s face, one is reaching out for, touching and manipulating it and its relation to other objects in the image.

All photos are to be understood as a conversation between the photographer, the photo-object and the viewer. The living picture asks us to slightly rebalance this delicate relationship by granting more power to the viewer; observing becomes more like a game when the image is placed in our hands as something to play with.

Is this a new paradigm in how social media content is engaged with?

Think of the content we post on Facebook or Twitter. Once posted, the productive role of others is not at the level of the content posted but to create new content peripherally around the original content. The productive potential for those interacting with content posted by others comes in the form of comments, likes, +1’s, thumbs up, retweets, rebloggs, etc. (social media vocabulary tends to proliferate beyond what it signifies). The status update, link, photo, geographic “check in” all remain largely unedited. It is nearly impossible to find mainstream examples of the content itself being interacted with. Status updates are rarely rewritten. Sometimes tweets are edited when retweeted (often using the MT or “modified tweet” indicator), but even these attempt to dutifully replicate the original meaning of the tweet being modified.

Photos in social media streams are typically to be stared at and scrolled through, not changed and manipulated. The interactivity with living pictures might be a meaningful, if subtle, change in the role of the viewer with respect to social media objects. These photo-objects ask more of those who encounter them.

These Living Pictures are Barely Alive

So far, I have described what is new about these images; what the “life” in “living pictures” refers to. However, this position is easy to overstate. Ultimately, these photos are barely alive and “revolutionary” this is not.

I’m reminded of my favorite essay by Theodore Adorno. In The Stars Down to Earth, he asked what are the pedagogical functions of technology? What does technology teach us to do?

The answer for those who purchase a Lytro camera is pretty simple: living picture technology teaches users to take photos that will look good at multiple focus points.

This answer is a counter-point to what I think might be a popular criticism of Lytro technology: “why would I want others choosing what is in focus? I took the photo wanting the focus a specific way.” No, living pictures are not the ability for others to alter what the photographer intended. Those using the Lytro camera will take photos with the various focal points in mind, positioning objects both in the foreground and background. Notice the photo-set on the Lytro website. The photos all contain something near and distant that both look good either in or out of focus.

Having objects at varying depths-of-field will entice others to click around in the image; precisely the process that breathes life into a so-called living picture. Learning to take photos in this style will maximize social media participation for those posting living pictures. The photos will generate more comments and will be more “like”-able.

What this implies is that while living pictures are slightly more interactive they certainly are not an example of photographers giving up control over the images they post. The amount of control turned over from the photographer to the viewer is quite minimal.

There is a very limited universe of possibilities provided to the viewer by the Lytro photo. The number of ways in which observers can bring “life” to (that is, refocus) the Lytro photo is quite minimal and because of this the photographer is well aware of the few different ways in which others will refocus the photo.

Yes, the Lytro photo can be seen in more than one way unlike other photos posted to social media. However, the new possibilities are quite minimal. Clicking through the current crop of living photos reveals that the user can choose between two or perhaps three significantly different focal points; all of which the photographer very likely had in mind either when shooting or at least when uploading the image.

What Would a Truly Living Photo Look Like?

The photo would have to take on a life of its own beyond what any one photographer or viewer intended. Writing in late-November 2011, the example seems obvious.

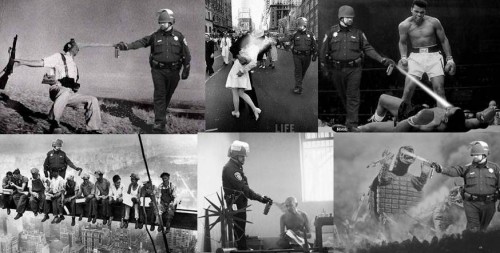

The now-infamous photo of Officer Pike pepper-spraying peaceful Occupy protesters at UC Davis serves as an example of an image come to life. The image of the “Casually Pepper Spray Everything Cop” has become a viral meme, taking on new forms no one could have ever imaged (a few examples are shows above). Instead of this, Lytro photos are still predetermined by those who took and shared the photo. A living picture contains more than just the creative energy of the photographer, but is fundamentally remixed with the energy, aesthetic and meanings of others; something that the Lytro photo does not achieve.

To conclude, the label “living picture” has been misapplied to Lytro technology. These photos are not alive and do not seem so revolutionary after all. However, they do mark a new way in which users might experience photos on social media: instead of leaning back, scrolling and clicking-through, viewers are enticed to lean forward and manipulate. Looking forward, will we see a larger trend towards sharing on social media becoming more remixable and interactive? Most people did not remix the pepper spray cop, and few of the photos we post on social media get such treatment, but Lytro’s technology begs the question: might more social media content one day truly come alive?

Photo of the week comes from the current protests in Egypt. The picture captures the flow of imagery across mediums, especially in times of protest. Al Jazeera ran the photo of a police officer who reportedly is shooting protesters in the eye. Infuriated, Egyptians stenciled his image on walls. The graffiti was then photographed and disseminated on social media, where Zeynep Tufekci saw the image and sent it to us. The image of the police officer flows from cameras to TV broadcast to paint on walls back into photo-form into social media and onto this blog where you see it now. Reality is augmented.

Photo of the week comes from the current protests in Egypt. The picture captures the flow of imagery across mediums, especially in times of protest. Al Jazeera ran the photo of a police officer who reportedly is shooting protesters in the eye. Infuriated, Egyptians stenciled his image on walls. The graffiti was then photographed and disseminated on social media, where Zeynep Tufekci saw the image and sent it to us. The image of the police officer flows from cameras to TV broadcast to paint on walls back into photo-form into social media and onto this blog where you see it now. Reality is augmented.

Meanwhile, this week on Cyborgology…

Jenny Davis writes about the mileage Facebook critics get out of misusing the word “friend”

David Banks gets into the Thanksgiving spirit and discusses sexism and Internet food videos

And we round up this week with the second part of Dan Greene’s “augmented syllabus” project

Image of the week. augmented reality: the online infiltrates how we perceive the offline, made literal here.

Image of the week. augmented reality: the online infiltrates how we perceive the offline, made literal here.

Meanwhile, it was busy this week on Cyborgology…

PJ Rey writes about Klout and how it infiltrates our mind’s eye

Nathan Jurgenson provides some initial reflections on the OWS Raid at Zuccotti park

PJ Rey gets Marxian and discusses value, productivity, labor and the web

Sarah Wanenchak reflects on the evolution of the ‘human microphone’ as Karl Rove gets mic-checked

In the 36 hours since the Occupy Wall Street raid removed protest infrastructure from Zuccotti Park, much of the conflict strikes me as the tension between the informational (the symbolic; media; ideas) and the material (physical; geographic). It runs through how New York City carried its actions out (at night, blocking journalists), the ensuing legal fight (does occupying physical space count as speech?) as well as the new strategic challenges facing an Occupy movement where camping is decreasingly an option.

Anyone who reads this blog knows that much of my work lies at the intersection of (1) information, media, technology, the online and (2) materiality, bodies and offline physical space. At this intersection, our reality is an “augmented” one. Part of the success of Occupy (and other recent protest movements) has been the awareness of just this point: by uniting media and information with the importance of flesh-and-blood bodies existing in physical space, our global atmosphere of dissent is increasingly one of an augmented revolution. Indeed, these are not protests centered online, as Jeff Jarvis tweeted this morning, or Zuccotti park, but in the augmented reality where the two intersect.

And this intersection of the power of the image and the power of the material dramatically came to a head about 36 hours ago as I write. In the early morning of November 15th, the two-month long occupation of Zuccotti Park was eliminated by the City of New York.

The Raid

The City and the NYPD were certainly thinking of both the material and the symbolic: in the grasping of physical property (Zuccotti Park), they simultaneously disallowed journalists to cover the raid; some of them arrested for trying. The New York Times, Huffington Post, and other newspapers are running stories about the so-called media blackout. The Committee to Protect Journalists has shunned the way coverage of the raid was largely prohibited. Rosie Gray, a writer for the Village Voice, tweeted that she yelled, “I’m press!” and an officer responded, “not tonight”. [Here is another good summary of press suppression at the OWS raid.]

The move on the part of the city in this information-war was to create what Agamben might call a “state of exception”; one where many traditional rules do not apply. Striking by surprise late at night and arresting journalists, it is clear that the strategy behind the raid had as much to do with controlling information as it did the park and the occupiers in it.

The symbolic upshot of all this will not, I think, fare well for the City or the NYPD. The unintended consequence of arresting journalists that night, of course, is that the vast majority of footage of the raid comes from the protesters themselves. The news articles above talk about a “media blackout” when, in reality, media was being produced. Photos and videos spread like wildfire when morning broke.

The narrative, the symbolic framing of the event specifically and the movement in general, once again, is in the hands of the protesters themselves. Unsure how to cover the movement, much of the traditional press has largely ignored Occupy with respect to the issues at stake. However, police brutality filmed by the protesters themselves has proven to be a powerful tool to capture national attention and sympathy on behalf of the movement.

The police, once again, treated the crowd as if they only existed in physical space. But the crowd took photos, livestreamed and once again took charge of the symbolism. The lasting images of the raid have massive symbolic power: hundreds of officers dressed in heavy riot-gear looking prepared to handle terrorists or a dangerous drug cartel were barreling down instead on a couple hundred unarmed peaceful campers. The draconian and seemingly hyperbolic display of force proves powerfully symbolic in further reifying the “us” versus “them” framework Occupy has so far successfully pushed.

Perhaps the only smart symbolic move on the part of the City was not destroying the 5,000-book People’s Library, but saving it and reportedly releasing it back to protesters today after heavy outcry over the possibility that it was destroyed. [EDIT: While Mayor Bloomberg’s office claimed to have preserved the People’s Library, new reports are claiming much of the library is still missing. If it turns out that the library was mostly destroyed, this further demonstrates the symbolic mismanagement on the part of the City and the NYPD. Books, of course, are highly symbolic of knowledge and the People’s Library a symbolic point of pride for OWS. Destroying books is symbolic of highly repressive and totalitarian control, again furthering the “few versus the many” rhetoric Occupy has provided from the start.]

The Current Legal Battle

The legal battles between Occupy and various cities also land precisely at this intersection of the material and informational. The issue at hand is the legality of having or evicting mass occupations of physical space, an issue that rests on what counts as “free speech.” On the one hand, some view speech as largely informational and mostly separate from occupying physical space. Others are arguing that occupying space is itself symbolic and is itself informational speech and should be equally protected. The case against Occupy is the conceptualization of the material and the informational as separate whereas the defense of Occupy believes that the two come together.

The fight has everything to do with this tension between the material and the informational. Part of New York City Mayor Bloomberg’s justification for the raid stated,

“Protestors have had two months to occupy the park with tents and sleeping bags. Now they will have to occupy the space with the power of their arguments.”

Again, the case against Occupy has been to split physical space (the park) and informational space (ideas, arguments, symbols, etc). I believe these are the grounds by which legal fights and protest strategies have been and will continue to be carried out.

Moving Forward

Opposed to what Bloomberg states above, as we know, occupying parks has been part of the argument the movement has been making all along. The symbolic power of sleeping at the park was immeasurable and now the movement increasingly has to face the reality that in some ways access to physical space is becoming scarcer.

Police efforts to clear Occupations across the United States continue to grow (so far, occupations have been cleared in Atlanta, Denver, New York City, Oakland, Portland, Salt Lake City, Seattle and Halifax in Canada). Thus, the Occupy movement has come to an inflection point: how can it continue to operate at both the level of the symbolic and simultaneously at the level of the physical? That double-punch has been a key to the movement’s success thus far.

The movement still has the #ows hashtag on Twitter, and, as @OccupyCincy tweeted, “Even if you remove our physical bodies, we are still here; in the psyche!” However the power of a hashtag can only be understood by acknowledging how it is fundamentally anchored by the physical offline occupations where human bodies are organizing, sleeping, yelling and marching. The Occupy movement going forward cannot forfeit either physical space or informational space but must remain fixated at the intersection of the two.

Image of the week is a photo Cyborgology editor Nathan Jurgenson took yesterday while visiting Marshall McLuhan’s Coach House at the University of Toronto. A former horse stable, this was the home of McLuhan’s research center and where he held his famous weekly seminars that attracted celebrities like John Lennon and Woody Allen. Many described the atmosphere as similar to Andy Warhol’s Factory.

This past week on Cyborgology…

David Banks reflected on the recent Society for the Social Studies of Science meetings in Cleveland

Image of the week is Julian Assange at Occupy London dressed as a Jedi.

Image of the week is Julian Assange at Occupy London dressed as a Jedi.

This week on Cyborgology…

Guest author Matt Rafalow wrote about technology in the classroom.

Things got spooky on Halloween when the Cyborgology editors talked about death and dying on the radio, Jenny Davis wrote about Postmodern Ghouls and Dave Strohecker linked us over to a zombie-takeover of the Huffington post.

And then things get serious when Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey co-author a piece about Facebook’s “frictionless sharing” as a new sort-of “digital paparazzi.”

Dave Strohecker looks at modern tattoo culture as it applies to the new tattoo-Barbie.

Have an idea for topics you would like to see covered on Cyborgology? Leave a comment! Want to guest-author something?

The role of new, social media in the Occupy protests near Wall Street, around the country and even around the globe is something I’ve written about before. I spent some time at Occupy Wall Street last week and talked to many folks there about technology. The story that emerged is much more complicated than expected. OWS has a more complicated, perhaps even “ironic” relationship with technology than I previous thought and that is often portrayed in the news and in everyday discussions.

It is easy to think of the Occupy protests as a bunch of young people who all blindly utilize Facebook, Twitter, SMS, digital photography and so on. And this is partially true. However, (1) not everyone at Occupy Wall Street is young; and (2), the role of technology is certainly not centered on the new, the high-tech or social media. At OWS, there is a focus on retro and analogue technologies; moving past a cultural fixation on the high-tech, OWS has opened a space for the low-tech.

What I want to think about there is the general Occupy Wall Street culture that has mixed-feelings about new technologies, even electricity itself. I will give examples of the embracing of retro-technology at OWS and consider three overlapping explanations for why this might be the case. I will also make use of some photographs I took while there.

Entering the Occupy Wall Street protests in Zuccotti Park, Manhattan, I was surprised how much old-school, retro, analogue and other “low-technologies” are embraced.

To be clear, I do not mean to say all technology at Occupy Wall Street is retro. There are laptops, a Wi-Fi network and smart phones uploading and responding to content across the web. Sometimes there is even a monitor/webcam setup that live-streams activity at the park (pictured below). Occupy utilizes both old and new technologies. And as I previously argued, they utilize both the on and offline; indeed this is an augmented revolution. However, the precise form of this technological augmentation needs to take into account how the OWS protests have an atemporal embracing of analogue and retro technologies and general distrust of the logic behind new technologies.

I spoke to many people at Occupy Wall Street about the technology situation in the park. I talked with various protesters and paid special attention to those dealing with technology and those whose role it was to provide general and press information. I should note that each person I talked to, be they a person who spends lots of time at the park or an “official” press contact, provided me with slightly different information; perhaps the result of the contradiction of having a spokesperson for a very decentralized group. However, as hours passed and people cycled through the park, I spoke to more and more individuals and a complicated picture developed.

I would hear two seemingly contradictory things, sometimes from the same person: (1) ‘I would be uploading more stuff to Facebook and Twitter if my phone was charged, but it is dead’; and (2) ‘we do not need electricity!’

So, why is this? Contradiction? Why the embracing of retro-tech? Does it have to do with ideology? Necessity? Both?

I want to provide three possible explanations. [*this list is not all-inclusive]

I. No Electricity, Duh

Perhaps the most obvious answer to why there is a love-hate relationship with new technologies has to do with the structural realities of the park itself; namely, the lack of electricity. There were some (at least 4) generators at the park when I was there. These were recently taken away and there is a fight to get them back. However, even with generators, electricity was sparse. The generators powered the media table (a modest amount of technology: laptops, printer, Wi-Fi router, webcam, TV) and charged some cell phones. Also, nearby food and newsstands were generally okay with letting protesters charge their phones (the protests are generating tourists and business in the area; I’ll have to force myself to leave ‘the commoditization of Occupy’ for another post).

But the story cannot be as simple as ‘there is little electricity so the protesters are using analogue tech.’ This does not explain why there is an embracing of analogue and why I was told over and over that “we don’t need electricity.”

Perhaps the structural reality (i.e., scarce electricity) has created a necessity to go analogue, which then has come to be embraced retroactively as something done intentionally? The ends required a new means, and now the means have come to be valued in and of themselves (to make a Simmelian argument).

A thought experiment: if electricity suddenly became abundant in Zuccotti Park, would more protesters be using their smart phones more of the time? Would there be more laptops open? I think so. In fact, I was told as much. However, would abundant electricity kill the retro-tech zeitgeist in the park? No, I do not think it would. And this is because there are other reasons for this mood.

II. It’s Politics: Rejecting the Logic of Consumer Technology Capitalism

To argue that the protesters embrace retro-technology only because there is little electricity misses the larger political reasoning that many, but probably not all, protesters in the park may have a general distrust of the role modern technology plays in our lives.

The contemporary logic of technology is a fixation on the high-tech: more, better, faster, smaller, cooler. All in the name of corporate profits. This has resulted in Apple’s treatment of workers in China, Google’s monopolistic, data-hungry capturing of more and more information, Facebook’s insidious creep into our private lives and the mounting piles of hazardous e-waste that we in the Global West export to the developing world. While new technologies are not fully abandoned at OWS, there is at least a questioning of the logic of new, shiny tech-toys as it relates to all of these growing problems.

There is the general mood at Zuccotti Park that humans are the most important technology that we have and that we live in a culture where we have become subservient to non-human technologies rather than the other way around. Instead, people, bodies and physical space are prioritized at the park. And when technology is needed, the embracing of low-technologies becomes a symbolic statement against this logic of high-technology-driven consumer capitalism.

For example, when engaging in the human-microphone, one quickly realizes that it becomes more than just a substitute for bullhorns, microphones and speakers. It becomes a powerful form of solidarity, it is a spectacle that gets the attention of the Occupy Tourists and it comes to stand for the resistance of the movement itself.

I should admit that no one protester told me all of this in plain language. This is my own extrapolation based on my general feeling of the protests and I invite others to disagree with me here. I think it is a plausible explanation given what Occupy is all about, but cannot claim I heard this directly from the protesters in any systematic way. More research would need to be done on this point.

III. Protesters Need Only to Pose

A third explanation for why there exists a love-hate relationship with new technologies at OWS goes back to one of the bulleted points above: those in Zuccotti park do not have to document themselves as much anymore because there is a crowd to do that for them. Again, tourists, journalists and other visitors have themselves been appropriated as a technology of documentation.

So much new, digital and social technologies center on documentation. A photo, status update, tweet, and the rest all are about documenting something: voicing your opinion, spreading news, giving detail or passing some other kind of information around. When the Occupy Wall Street protests were smaller, and this is still the case with most regional Occupations, the protesters themselves were organizing on Facebook, spreading the word with Twitter hashtags and shooting photos and videos of their numbers and suspected police brutality.

Things have changed a bit for OWS. Today, Zuccotti Park is a major tourist destination. Massive crowds with fully-charged cameras are snapping away. Journalists and other interested parties have increasingly been documenting the movement. And there are loads of photographers around every corner shooting the scene (I was one of them). Occupy Wall Street has much of the attention they asked for and this has positioned themselves on the other side of the camera lens.

And this is why the protesters have gotten very good at posing. The drum circle is set up facing the crowd of tourists; separated by a metal gate just like a rock concert. They drum, put on their show, and people stand at the gates with cameras. One scene I saw over and over again in the park was a protester seeing someone point a camera at them and immediately freeze staring off into space. The protester attempts to pose as unposed, the camera-person attempts to pass the photo off as spontaneous. Simply put, the protesters are very aware that their every move is being documented and react accordingly. Like reality show contestants or modern famous-for-being-famous celebrities, those in Zuccotti Park adhere to the logic of ubiquitous cameras by becoming photogenic.

To be clear, I say none of this as a put-down to the protestors. I know that, typically, “posing” is a word used pejoratively (“poser” is an insult). However, it strikes me that the protesters are effectively using the power of the gaze: they use the power inherent in being watched to portray what they want. Lacking electricity, the OWS protesters have turned tourists into Twitter. Instead of having to shoot their own photos, post them and hope for an audience, the OWS protester learns instead to be photogenic, luring the cameraperson to compose, snap, post and disseminate; an efficient and effective strategy in the image-economy.

To conclude, all of this is only my initial speculations about the very interesting role technology plays in the Occupy Wall Street protests. The technology of the movement is not just how they have utilized the new and the high tech but also the embracing of low-technologies. Much more could be said and other perspectives should be entertained. Further, it must be the case that all of this plays out quite differently at different local Occupy protests. Hopefully that is a discussion we can have on this blog in the near future.

follow nathan on Twitter: @nathanjurgenson

Last week, Cyborgology editors Nathan Jurgenson and PJ Rey were on WYPR (Baltimore’s NPR affiliate) talking about death and dying on Facebook. This is part of the conversation, the rest will be aired in the near future.