Instagram has gained tremendous popularity over the last several years. It is popular with people of all sorts of demographics and from all walks of life. In the case with Instagram, the number of followers that you acquire is what is most important.

Number of followers equals Instagram success

It is important to be aware here that there is a lot more to Instagram than just the number of followers you can acquire. However, your number of followers is one of the important measurements (or metrics) of the social media tool. If you have a large number of followers, other people will have the perception that you (and your business) are a success. That lends itself to your professional credibility and trustworthiness.

For business progress, buying followers on Instagram can give you a lot of popularity. A strong number of followers also gives you the confidence that your message is being received by other people online and it allows you to increase your reach to a large number of good-quality connections. It also goes a long way to strengthening your relationship with your target audience, which is essential to your success.

Instagram is a smart phone application that acts as a social network and photo editing software. The application allows users to apply various filters and effects to their camera phone pictures, often in order to look like Polaroids from the 70s. The users can then upload the photos to the Instagram community where other members can view, “like”, and comment on them. A user’s Instagram feed can also be synced with other social networking platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Flickr.

Launched in 2010, the app was initially only available to iPhone users and those with iOS software. Its popularity became instant, and within a year, it had over ten million users. In April 2012, Instagram debuted their Android version of the app on the Google Play store, thus opening up its user base to those with Android smartphones. With this launch came an unexpected backlash from the original iPhone users, and a new form of class warfare began to arise on the internet.

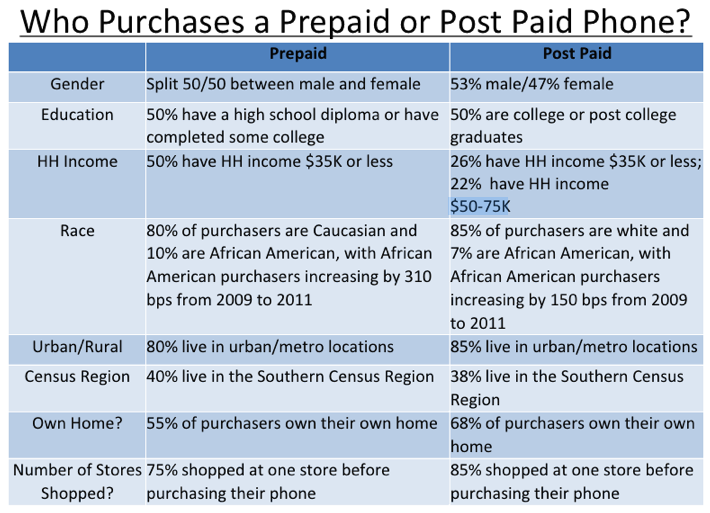

Different cell phone providers offer iPhone versus Android devices. iPhones can only be purchased with the three big name cell phone providers in the US (Sprint, Verizon, and AT&T) and are often sold at a discounted rate with a 2-year contract. These providers offer Android phones too, but the Android phones can also be sold with a pre-paid plan through companies like Boost Mobile, Virgin Mobile, Cricket, and Walmart’s Straight Talk. With these different businesses come different sets of customers. According to a Stevenson survey, 50% of all prepaid cellphone users have a high school diploma or completed some college whereas 50% of those with contracts are college or post-college graduates. Racially speaking, 10% of all prepaid users are African American as well versus 7% of those with cellphone contracts, and those prepaid users are increasing 1.6% more than contract users.

In August 2011, the website Hunch published an infographic highlighting various differences between Android and iPhone users. Of the 700,000 users surveyed between March 2009 to July 2011, 80% of all Android users are more likely to have only a high school diploma versus 37% of iPhone users having a graduate degree. Android users are also 24% more likely to earn between $50,000 to $100,000 annually whereas 67% of iPhone users are more likely to earn over $200,000. These vast differences in income and education reflect sociology’s constant references to the dissimilarities between the working and bourgeoisie class.

Full infographic available here: http://blog.hunch.com/?p=51781

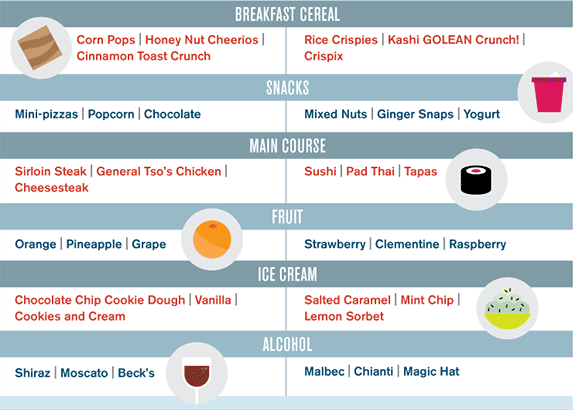

A typical Android dinner consists of sirloin steak, General Tso’s chicken, or cheesesteak. While General Tso’s chicken could be considered an exotic and ethnic dish, it is an Americanized Chinese meal born in New York City. Protein-heavy and fatty dishes such as these make food “a material reality, a nourishing substance which sustains the body and gives strength” (Bourdieu 1984: 197) and further align Android users with Bourdieu’s working-class.

This class distinction between bourgeois and working is even more prevalent in different smartphone users’ ice cream choices. Android users enjoy the simple flavors of chocolate chip cookie dough, vanilla, and cookies and cream. These are easily found in any grocery store’s freezer section or ice cream parlor. By contrast, iPhone users like the flavors salted caramel, mint chip, and lemon sorbet. It’s like comparing a quart-sized carton of Dreyer’s ice cream to a pint of Häagen-Dazs.

These very different demographics and cultural preferences combined with the overtly negative and elitist Twitter posts from Instagram iPhone users highlight a very important issue in today’s digital culture. Despite residing in the classless, race-less, and even gender-less world of cyberspace, prejudice still reels its ugly head on the internet. All these findings can relate back to Eszter Hargittai’s article, “The Digital Reproduction of Inequality” and her concept of digital inequality. Hargittai’s expands on the idea of the digital divide to define digital inequality as “a more refined approach [that] considers different aspects of the divide, focusing on such details as quality of equipment, autonomy of use, the presence of social support networks, experience and user skills, in addition to differences in types of uses” (Hargittai 2008: 937).

Applying her argument to Android and iOS users, we can see the differences between these users show that “while all population segments may have become increasingly connected, serious divides persist with the most disadvantaged trailing behind the more privileged in significant ways” (Hargittai 2008: 938). These distinctions create digital inequality in the realm of cellphone usage and highlights how “differentiated uses of digital media have the potential to lead to increasing inequalities benefiting those who are already in advantageous positions and denying access to better resources to the underprivileged” (Hargittai 2008: 943).

Digital inequality can become even more persistent as well because it ensures “that people’s socioeconomic status influences the ways in which they have access to and use information and communication technologies” (Hargittai 2008: 939). Even though Instagram was launched in 2010 through the iTunes store, Android users didn’t get to access until 2012. This two-year gap created a distinct user base and sense of entitlement amongst the iPhone Instagram community. The user base was even further isolated through the way in which Instagram acts as a social network. There is no online access to the app or photos through their website. The only way users can browse and share photos is through their cellphone. Therefore, Android users couldn’t access this “gated community,” allowing them to be further alienated and seen as unwanted intruders storming the gates of the sacred iPhone community.

The Instagram social network will probably become an even stronger community now that Facebook purchased it for $1 billion. Instagram has the ability to create internet celebrities based on whatever images a user happens to post. With a user’s status in increased popularity come various forms of financial success. For example, as seen with the popularity of different Tumblr blogs, a well followed feed can lead to lucrative book deals. Perhaps art gallery openings featuring Instagram photographers will soon be on the horizon — oh, wait, that already happened.

Digital inequality will continue to persist as app developers choose to limit which mobile operating systems have access to their own technologies. For example, the popular sharing and bookmarking site Pinterest has yet to launch an official app through the Google Play store, but there is one available for free on iTunes. While the Pinterest is also accessible online, thus allowing all internet users to access its services, preventing easy smartphone/tablet use still limits the audience of those wishing to engage in the community while away from a computer. As we become even more reliant on mobile devices, this divide will become an even bigger issue and highlight major differences through technology use in various communities. It’s a very optimistic, but now faded notion, to see the internet as “The Information Superhighway.” In reality, the highway is turning more into “The Information Toll Road” as technology evolves.

Sources: Twitter, BuzzFeed 1, 2, Lifehacker, CNET, Hunch, Distinction, GigaOM, Huffington Post, Mashable 1, 2, Tumblr, and The Digital Reproduction of Inequality

Christine Moore studies sexuality and is currently pursuing her Masters in sociology at the University of Texas San Antonio. She reluctantly tweets @thisthingblows.

Azza A. Raslan (

Azza A. Raslan ( Zeynep Tufekci (

Zeynep Tufekci ( Dave Parry (

Dave Parry (

To close, we might think of some questions to frame this issue moving forward: What slice of the bigger picture do we get when relying on social media for journalism?

To close, we might think of some questions to frame this issue moving forward: What slice of the bigger picture do we get when relying on social media for journalism?