Writing Tools and the Instrumentalist Conception of Technology My recent article in The Atlantic, “The Philosophy of the Technology of the Gun,” is provocative in part because it suggests tools like guns might have more power of us than meets the eye. Given widely held views about autonomy (e.g., the notion that “guns don’t kill people, people kill people”), this alternative way of looking at things can cause anxiety, especially when misunderstood and translated into terms like those offered by the first commenter, “Guns are magic mind control machines.” The article presented an account of how humans relate to technology, and to further illuminate those relations, I’ll briefly revisit media theorist Friedrich Kittler’s take on Friedrich Nietzche’s use of the typewriter. Like my gun essay, this analysis challenges the “instrumentalist” conception of technology.

My recent article in The Atlantic, “The Philosophy of the Technology of the Gun,” is provocative in part because it suggests tools like guns might have more power of us than meets the eye. Given widely held views about autonomy (e.g., the notion that “guns don’t kill people, people kill people”), this alternative way of looking at things can cause anxiety, especially when misunderstood and translated into terms like those offered by the first commenter, “Guns are magic mind control machines.” The article presented an account of how humans relate to technology, and to further illuminate those relations, I’ll briefly revisit media theorist Friedrich Kittler’s take on Friedrich Nietzche’s use of the typewriter. Like my gun essay, this analysis challenges the “instrumentalist” conception of technology.

In Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Kittler contends that in order to understand how Nietzsche coped with myopia, it is crucial to grasp the import of him by buying a typewriter: a Danish model invented by Hans Rasmus Johann Malling Hanson. Given the lack of philosophical precedent, Kittler characterizes Nietzsche as the “first mechanized philosopher,” and argues that integrating the typewriter into the writing process facilitated several changes to the act of writing itself, profoundly impacting Nietzsche’s thought and style.

Kittler stresses how typewriters alter the physical connection between writer and text. Unlike the visual attention that writing by hand requires, the typewriter made it possible to create texts by exploiting a blind, tactile power that can harness “a historically new proficiency: écriture automatique.” Given the report of a Frankfurt eye doctor, which stated that Nietzsche’s “right eye could only perceive mistaken and distorted images,” and Nietzsche’s own claim to find reading and writing painful after twenty minutes, we can appreciate why he would turn to a writing device that could be operated simply by pressing briefly on a key—a key that doesn’t even need to be looked at. Indeed, the Malling Hanson was specifically designed to “compensate for physical deficiencies” by having the capacity to “be guided solely by one’s sense of touch.”

When considering this shift from sight to touch, it is instructive to follow Kittler’s lead and recall that by the 1940’s, Martin Heidegger, a philosopher who might have ethical blindness, but did not suffer from Nietzsche’s physical maladies, famously expressed a position about automatic writing that ran contrary to Nietzsche’s enthusiasm. Underwritten by a conception of the human hand being utterly distinctive, Heidegger articulated distain for the typewriter’s speediness. He preferred the slower moving ink pen, insisting the device is more conducive to fostering deep philosophical thought. When discussing the Greek sense of action, pragma, in his lectures on Parmenides, Heidegger thus makes the following claims,

Man himself acts [handelt] through the hand [Hand]; for the hand is, together with the word, the essential distinction of man. Only a being which, like man, “has” the word, can and must “have” “the hand.”…No animal has a hand and a hand never originates from a paw or claw or talon…The hand sprang forth only out of the word and together with the word. Man does not “have” hands, but the hand holds the essence of man, because the word as the essential realm of the hand is the ground of the essence of man. The word as what is inscribed and what appears is the written word, i.e., script. And the word as script is handwriting.

It is not accidental that the modern man writes “with” the typewriter and “dictates” [diktiert] “into” a machine. This “history” of writing is one of the man reasons for the increasing destruction of the word. The latter no longer comes and goes by means of the writing hand, the properly acting hand, but b the means of the mechanical forces it releases. The typewriter tears writing from the essential realm of the hand, i.e., the realm of the word. The word itself turns into something “typed.”…Mechanical writing deprives the hand of its rank in the realm of the written word and degrades the word to a means of communication.

This is not the appropriate space to try to resolve the different philosophical perspectives on the typewriter. Doing so would require a detailed discussion of whether Heidegger’s position depends upon unjustifiable skepticism about natural evolution, and whether his conclusions lead to a nostalgia regress. Would a quill or reed pen be even better? Should the “authentic” writer make his or her own paper? Rather, the value of calling attention to the core issue over which Nietzsche and Heidegger diverge is that it allows us to emphasize a crucial point of commonality. Both philosophers agree that material culture can have a profound influence upon thought and, thereby, upon the kind of subject who thinks in particular way.

Kittler further stresses the fact that typed texts display a different visual configuration than handwritten ones. Unlike handwritten documents, typed manuscripts distribute spatially discrete signs of standardized size. Such uniformity could appeal to Nietzsche precisely because it fused what Marshal McLuhan calls “composition and publication.” It enabled “a half-blind writer chased by publishers…to produce ‘documents as beautiful and standardized as print.”

Finally, and most significantly, Kittler makes the following rather startling claim about Nietzsche’s response:

Nietzsche, as proud of the publication of his mechanization as any philosopher, changed from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style. That is precisely what is meant by the sentence our writing tools are also working on our thoughts. Malling Hansen’s writing ball, with its operating difficulties, made Nietzsche into a laconic.

Kittler’s point, then, is that when Nietzsche challenged conventional modes of philosophical expression, he didn’t opt for epigraphs simply because he believed the style would dramatically impact readers—more so than, say, lengthy texts comprised of logically arranged propositions. Rather, Nietzsche’s decision to “artistically” confront the problem of communication emerged from a combination factors: his views on language, the physical limitations imposed by his ailments, and the horizon of possibilities that the typewriter affords. Given the importance of all three, Kittler cites a poem that Nietzsche wrote about the Malling Hansen in 1882. Translated, it states:

THE WRITING BALL IS A THING LIKE ME: MADE OF /IRON/ YET EASILY TWISTED ON JOURNEYS./ PATIENCE AND TACT ARE REQUIRED IN ADBUNDANCE,/ AS WELL AS FINE FINGERS, TO USE US.

By comparing “the equipment, the thing, and the agent,” Nietzsche appears to demonstrate his awareness that “authors” do not generate thoughts that transcend their material culture.

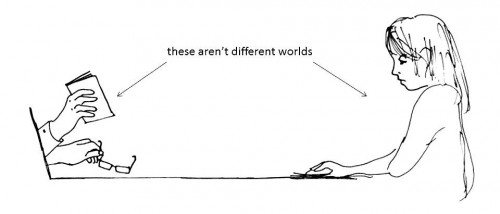

Obviously, much has changed since Nietzsche wrote with a typewriter. That technology largely has faded from practice, and for the most part, become a relic replaced by various forms of computer-mediated programs. Nevertheless, the manner in which the typewriter impacts cognition is paralleled by changes brought upon by current digital writing tools.

Michael Chabon, for example, listed software (DevonThink Pro and Nisus Writer Express) in the acknowledgement section to his highly acclaimed novel, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union. If the instrumentalist view of technology were correct, this attribution should strike us as absurd. According to the instrumentalist outlook, people can be good or bad collaborators. Pen, paper, typewriters, and computers are merely artifacts that good writers use well, and bad writers use poorly. Indeed, for the instrumentalist, it is bad faith to associate the quality of writing with its underlying material culture; an artist in denial blames his or her tools to avoid the painful realization that he or she lacks talent. And yet, Chabon isn’t blaming a dry spell or a poor novel on his tools. Remarkably, he is doing the opposite. Instead of taking all the credit for his accomplishment, he’s challenging perceptions of autonomy by distributing its value to a human-machine interface.

The significance of Chabon’s comments—and Kittler and Heidegger’s analyses—extends beyond the topic of writers and their tools. To grasp the effects of computers have on society, we need to carefully reflect on the distortions that arise when the instrumentalist perspective pervades coverage of social media. The go-to phrase, “the Web is just a tool” is as off-base as the NRA slogan, “Guns don’t kill people. People kill people.”

Evan Selinger is an associate professor of philosophy at Rochester Institute of Technology. Follow him on Twitter: @evanselinger

Matthew Morrison

– “Queering Intimacy: Class, Coupling, and the Internet in Gay Life”

Matthew Morrison

– “Queering Intimacy: Class, Coupling, and the Internet in Gay Life” Alice Marwick

(

Alice Marwick

( Kelsey Brannan – “Grindr – Browsing and Geolocating Sexiness”

Kelsey Brannan – “Grindr – Browsing and Geolocating Sexiness”