I have been thinking through ideas on this blog for my dissertation project about how we document ourselves on social media. I recently posted some thoughts on rethinking privacy and publicity and I posted an earlier long essay on the rise of faux-vintage Hipstamatic and Instagram photos. There, I discussed the “camera eye” as a metaphor for how we are being trained to view our present as always its potential documentation in the form of a tweet, photo, status update, etc. (what I call “documentary vision”). The photographer knows well that after taking many pictures one’s eye becomes like the viewfinder: always viewing the world through the logic of the camera mechanism via framing, lighting, depth of field, focus, movement and so on. Even without the camera in hand the world becomes transformed into the status of the potential-photograph. And with social media we have become like the photographer: our brains always looking for moments where the ephemeral blur of lived experience might best be translated into its documented form.

I have been thinking through ideas on this blog for my dissertation project about how we document ourselves on social media. I recently posted some thoughts on rethinking privacy and publicity and I posted an earlier long essay on the rise of faux-vintage Hipstamatic and Instagram photos. There, I discussed the “camera eye” as a metaphor for how we are being trained to view our present as always its potential documentation in the form of a tweet, photo, status update, etc. (what I call “documentary vision”). The photographer knows well that after taking many pictures one’s eye becomes like the viewfinder: always viewing the world through the logic of the camera mechanism via framing, lighting, depth of field, focus, movement and so on. Even without the camera in hand the world becomes transformed into the status of the potential-photograph. And with social media we have become like the photographer: our brains always looking for moments where the ephemeral blur of lived experience might best be translated into its documented form.

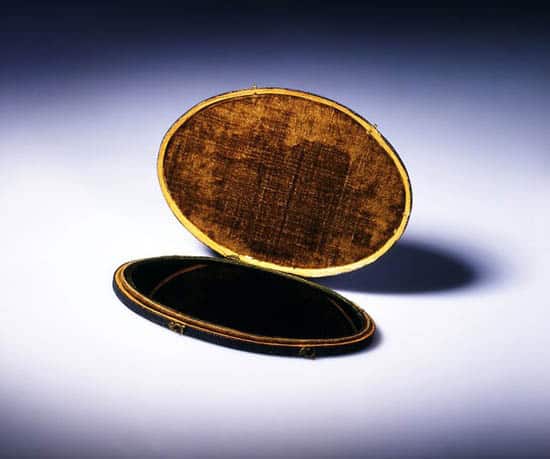

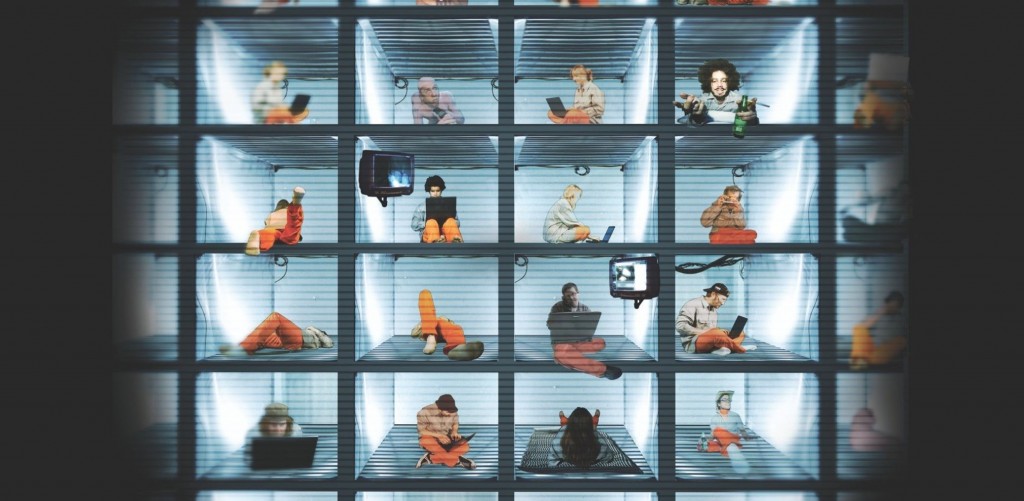

I would like to expand on this point by going back a little further in the history of documentation technologies to the 17th century Claude glass (pictured above) to provide insight into how we position ourselves to the world around us in the age of social media.

Do I have to make the case that self-documentation has expanded with social media? As I type this in a local bar, I know that I can “check-in” on Foursquare, tweet a funny one-liner just overheard, post a quick status update on Facebook letting everyone know that I am working from a bar, snap an interesting photo (or video) of my drink and this glowing screen, and, while I’m at it, write a short review of the place on Yelp. And I can do all of this on my phone in a matter of minutes.

While self-documentation is nothing new, the level and ubiquity of documentation possibilities afforded by social media, as well as the normalcy to which we engage in them, surely is. And, most importantly, sites like Facebook, for the first time, guarantee an audience. Thus, social media provides both the opportunity and motivation to self-document as never before.

What does any of this have to do with the Claude glass, a little-known 17th century mirror-device?

The Claude glass is (usually) a small (usually) convex mirror that is (usually) the color grey (the darkened color gave it the nickname “black mirror”). The device assisted 17th and 18th century “picturesque” landscape painters, especially those attempting to emulate the popular paintings of Claude Lorrain (whom the device is named after). By standing with their back to the landscape and towards the Claude glass mirror, the viewer is provided with a mirror-image of the landscape behind them. The mirror’s convex shape pushes more scenery into a single focal point in the reflection (which was considered aesthetically pleasing in the “picturesque” genre). And the grey-smoke coloring of the lens changes the tones of the reflection to those that are more easily reproduced with the limited color palette painters employ.

The Claude glass also came to be used by more than painters. Wealthy English vacationers took countryside vacations in search of “picturesque”-style landscapes reminiscent of the famous paintings. These tourists would often carry a Claude glass in their pocket so that they could turn around and view the world, slightly convexed and re-colored, as if it were a painting. Often, they would also use the device to make a sketch, wanting to return home with some documentation of the beauty witnessed on vacation. Competent in what is picturesque, the wealthy demonstrated their “superior” cultured taste distinct from lower and middle classes as well as the new rich. This trend is well documented in the book, The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art by Arnaud Maillet (2004).

The term “picturesque” as the name for this trend is important to clarify. It refers to what which is worthy of emulation and documentation; to resemble or be suitable for a picture (which, in the 17th and 18th centuries meant a painting). Importantly, that which is “picturesque” is typically associated with beauty, even though many scenes worthy of pictoral documentation are not necessarily beautiful (a horrific war-scene, for instance). Thus, the Claude glass was sort-of like the Hipstamatic or Instagram of its day: it presented lived reality as more beautiful and already in its documented form (be it a painting or a faux-vintage photograph). Indeed, there are similarities in style between Claude Lorrain’s paintings, the images seen in the Claude glass and the effects that the faux-vintage photo filters employ.

Digitally Picturesque

The Claude glass presents us with an image of the tourist standing exactly away from that which they have traveled to see. Instead, the favored vantage-point is of reality already as an idealized documentation. Both the Claude glass and the Hipstamatic photo present this type of so-called nostalgia for the present. I think this a useful metaphor for how we self-document on social media. Let’s split this parallel between the Claude glass and Facebook into three separate points:

First, the Clade glass metaphor jives with the notion of the “camera eye” that I have used previously. They are both examples of what I call “documentary vision,” that is, the habit of viewing reality in the present as always a potential document (often to be posted across social media). We are like the 18th century tourist in that we search for the “picturesque” in our world to demonstrate that we are living a life worthy of documentation; be it literally in a picture, or in a tweet, status update, etc.

Second, the Claude glass model presents the Facebook user as turned away from the lived experience that they are diligently documenting, opposed to the “camera eye” metaphor of facing forward towards reality. One worry surrounding social media is that our fixation on documenting our lives might hinder our ability to live in the moment. Do those fixated on shooting photos and video of a concert miss out on the live performance to some degree? Do those who travel with a camera constantly in-hand sacrifice experiencing the new locale in the here-and-now? Does our increasing fixation with self-documentation position us, like the Claude glass user, precisely away from the lived experience we are documenting?

Third, the Claude glass is affiliated with the “picturesque” movement that equated beauty with being worthy of pictoral representation. The Claude glass model would describe our use of social media as the attempt to present our lives as more beautiful and interesting than they really are (a reality we have turned our backs on). When our reality is too banal we might reshape the image of ourselves just a bit to make our Friday night seem a bit more exciting, our insights more witty, or homes to be better furnished, the food we cook more delicious, our film selections more exotic, our pets more adorable and so on (which creates what Jenna Wortham calls “the fear of missing out”).

To conclude, these last two points demonstrate how the model of Claude glass self-documentation on social media differs from “the camera eye.” Both the camera and the Claude glass share the effect of developing a view of the world as one of constant potential documentation. The difference is that the Claude glass metaphor presents the social media user as turned away from lived experience in order to present it as more picturesque than it really is. Thus, the questions I am still working on and those I would like to pose to you become: Does this capture the reality of the Facebook user? Are we missing out on reality as we attempt to document it? Are we portraying ourselves and lives as better than they actually are?

Header image source: http://carterseddon.com/claude1.html

Check out The Big Ideas podcast over at The Guardian UK today for

Check out The Big Ideas podcast over at The Guardian UK today for

The stigma surrounding having imperfections online

The stigma surrounding having imperfections online