This post originally appeared on The Frailest Thing and is replicated here with permission.

By one of those odd twists of associative memory, John Caputo’s little book, On Religion, recently came to mind. Caputo, a well regarded interpreter of Jacques Derrida and a philosopher in the continental tradition, opened with a question culled from the work of Augustine of Hippo. Splicing two lines from Augustine’s Confessions, Caputo framed his study by asking, “What do I love when I love my God?”

I appreciate this formulation because it forces a certain self-critical introspection. It refuses the comforts of thoughtlessness. Precisely where some might be most inclined to rely on taken-for-granted assumptions and unquestioned constructs, Caputo’s Augustinian query interjects a searching critique. And it is the structure of the question that I want to borrow to consider one dimension what we are doing when we use social media.

But first, a little more from Caputo who takes the liberty of elaborating on the spirit of Augustine’s quest. Channeling the African saint, Caputo writes, “… I am after something, driven to and fro by my restless search for something, by a deep desire, indeed by a desire beyond desire, beyond particular desires for particular things, by a desire for I-know-not-what, for something impossible. Still, even if we are lifted on the wings of such a love, the question remains, what do I love, what am I seeking?”

Then Caputo makes an important observation. “When Augustine talks like this,” he cautions, “we ought not to think of him as stricken by a great hole or lack or emptiness which he is seeking to fill up, but as someone overflowing with love who is seeking to know where to direct his love.”

Not too long ago I posted some thoughts on what I took to be the Augustinian notes sounded in Matt Honan’s account of his time at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas and Kevin Kelly’s subsequent reflections on Honan’s experience. In that post, I employed the very language Caputo cautioned against — in part because Honan’s rhetoric invited it. But now I’m chastened; I’m inclined to think that Caputo is on to something. His distinction is not merely academic and I’ll return to it a little further on.

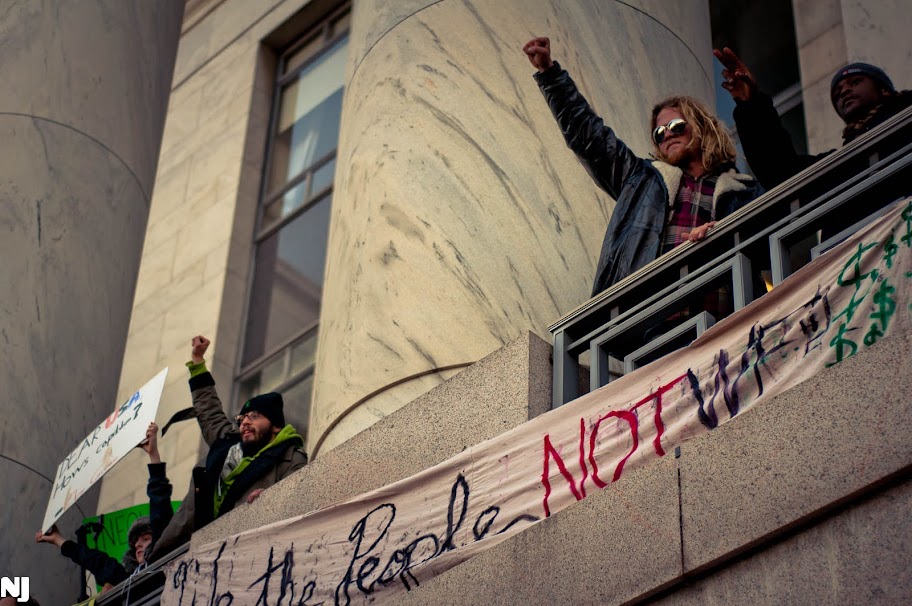

Plummeting, perhaps, from the sublime to the … what to call it, let us just say the ordinary, the formulation of Caputo’s question somehow triggered a more contemporary re-articulation: “What do I like when I “Like” on Facebook?” Putting it this way suggests that what I like may not, in fact, be what I “Like”. The question pushes us to examine why it is that we do what we do in social media contexts (Facebook being here merely a synecdoche).

What we do on social media platforms is often analyzed as a performance or construction of the self. On this view, what we are doing is giving shape to our identity. What we “Like” is the projected identity, or better yet, the perception and affirmation of that identity by others. This, of course, does not exhaust what is done with social media, but it is an important and pervasive element.

When we think about social media as a field for the construction and enactment of identities, we tend to think of it as the projection, authentic or inauthentic, of a fixed reality. But perhaps we would do well to consider the possibility that identity on social networks is not so much being performed as it is being sought, that behind the identity-work on social media platforms there is an inchoate and fluid reality seeking to take shape by expending itself.

Caputo distinguished between love or desire understood as a lack seeking to be filled and love or desire understood as a surplus seeking to be expended. This distinction can be usefully mapped over the motivations driving our social media activity. Sometimes we preform our identities seeking to fill a desire structured as a lack experienced by an ostensibly consistent self. At other times the performance amounts to a less coherent project, the expenditure of desire structured as a surplus in search of itself.

The entanglement of our loves (or, likes) and our identity on social media has, it turns out, an antecedent in the Augustinian articulation of the human condition. Caputo went on to note that the question of what we love is also bound up with another Augustinian query: “Augustine’s question — ‘what do I love when I love my God?’ — persists as a life-long and irreducible question … because that question is entangled with the other persistent Augustinian question, ‘who am I?’”

What we love and desire and who we are — these two are bound up irrevocably with one another.

“I have been made a question to myself,” Augustine famously declared. And so it is with all of us. The problem with our talk about the performance of identity is that it too often tacitly assumes a fixed and knowing identity engaging in the performance. The reality, as Augustine understood, is more complex and whatever it is we are doing online is tied up with that complexity.

L. M. Sacasas is a PhD student in the University of Central Florida’s “Texts & Technology” program exploring the intersections of bodies, spaces, and technology. He blogs at The Frailest Thing and you can follow his tweets at @FrailestThing