Natan Sznaider, Academic College of Tel-Aviv-Yaffo

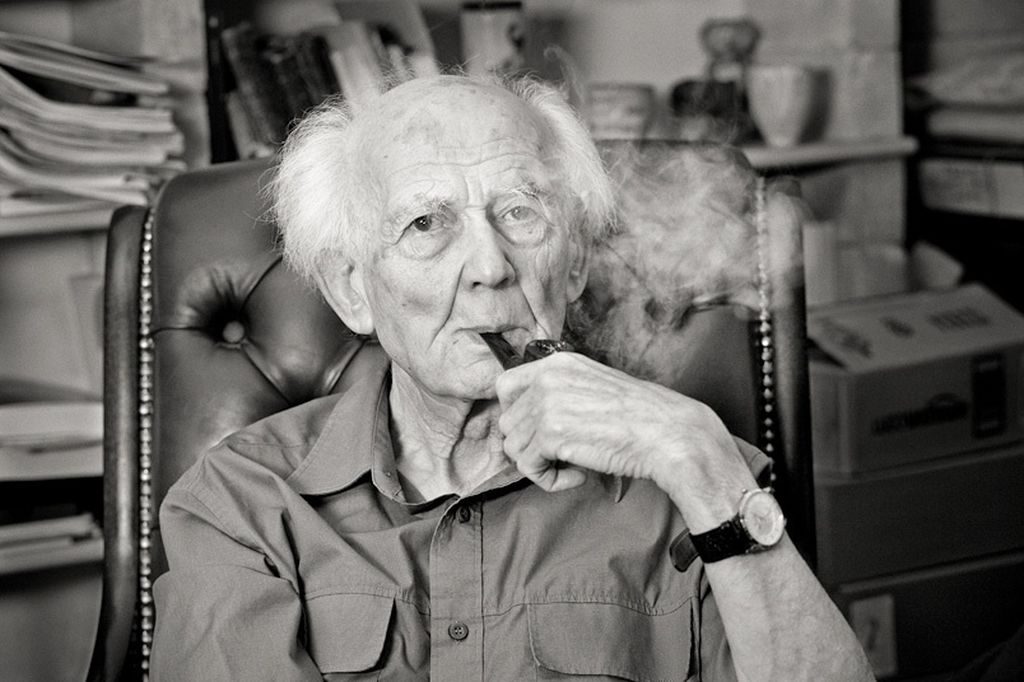

Many of us were deeply impressed when Zygmunt Bauman published his “Modernity and the Holocaust” almost a quarter century ago. When I studied sociology in the 1970s there was not much sociological thinking going around about the Holocaust.

When the book came out we weren’t very aware of the consequences. The book came out when the Berlin Wall fell and one year later, Germany was reunified and I would argue that these things are connected. Bauman himself was much more aware of the context. In his Amalfi Prize lecture Bauman was very clear about the context of his book and I quote him: “The ideas that went into the book knew of no divide; they knew only of our common European experience, of our shared history whose unity may be belied, even temporarily suppressed, but not broken. It is our joint, all European, fate that my book is addressing“ (p.208 of the second edition of Modernity and the Holocaust).

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy

What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations.

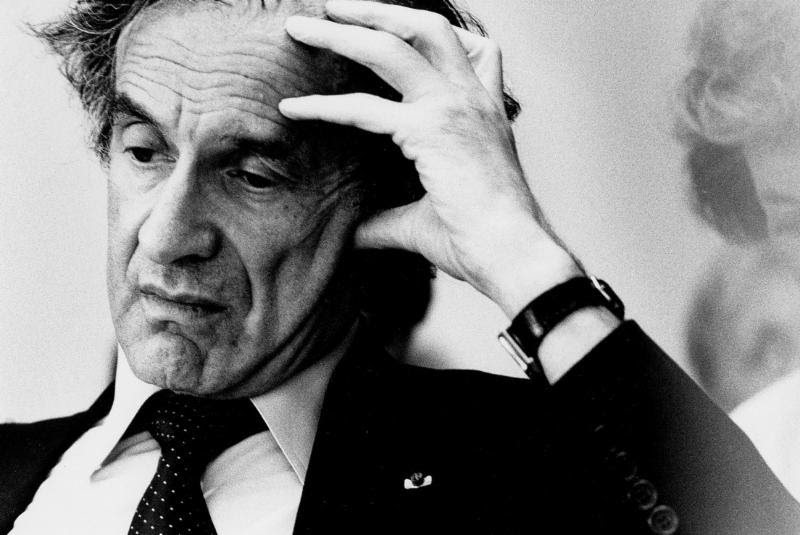

There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations. Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch. This volume offers a trans-national, comparative perspective on the varied reactions of the neutral countries to the Nazi persecution and murder of the European Jews. It includes a chapter by CHGS director Alejandro Baer and historian Pedro Correa entitled “The Politics of Holocaust Rescue Myths in Spain.”

This volume offers a trans-national, comparative perspective on the varied reactions of the neutral countries to the Nazi persecution and murder of the European Jews. It includes a chapter by CHGS director Alejandro Baer and historian Pedro Correa entitled “The Politics of Holocaust Rescue Myths in Spain.”

In 1999 Joschka Fischer, Germany’s Foreign Minister and a member of the Green Party with strong pacifist roots, used the phrase “Never Again Auschwitz” to support German military intervention during the Kosovo crisis. In 2005, at the main ceremony to mark the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp, Russian President Vladimir Putin praised the Red Army for “liberating Europe” (an assertion that obviously did not resonate positively among Poles). In the summer of 2014 Turkish President Recep Erdoğan slammed Israel for betraying the memory of the Holocaust by “acting like Nazis” during the operation against Hamas in Gaza. At the same time Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu invoked the Holocaust to warn the world of a nuclear Iran.

In 1999 Joschka Fischer, Germany’s Foreign Minister and a member of the Green Party with strong pacifist roots, used the phrase “Never Again Auschwitz” to support German military intervention during the Kosovo crisis. In 2005, at the main ceremony to mark the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp, Russian President Vladimir Putin praised the Red Army for “liberating Europe” (an assertion that obviously did not resonate positively among Poles). In the summer of 2014 Turkish President Recep Erdoğan slammed Israel for betraying the memory of the Holocaust by “acting like Nazis” during the operation against Hamas in Gaza. At the same time Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu invoked the Holocaust to warn the world of a nuclear Iran. Son of Saul is a film about a member of the

Son of Saul is a film about a member of the