Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

Elie Wiesel had a profound effect on my life. In 1997 I embarked on a journey to earn my Master’s degree from the University of Minnesota. At the time that I began my classes I had no thoughts of studying the Holocaust, but through a series of small events, I found myself thinking of nothing else. I do not remember when I read Night, nor do I recall what led me to return to Wiesel’s work while in graduate school. For some reason I turned to a little known collection of his short stories titled One Generation After, published in 1970. How the book found its way from my mother’s bookshelf to mine is not clear, but for some reason, I picked it up and read it. The story that changed my life was “The Watch.” Over the course of six pages, Wiesel tells of his return to his home of Sighet, Romania and the clandestine mission he undertakes to recover the watch given to him by his parents on the eve of his Bar Mitzvah. It is the last gift he received prior to being transported with his family to Auschwitz. Like many Jewish families, fearing the unknown and hoping for an eventual return, he buried it in the backyard of their home. Miraculously, he finds it, and quickly begins to dream of bringing it back to life. However, in the end he decides to put it back in its resting place. He hopes that some future child will dig it up and realize that once Jewish children had lived and sadly been robbed of their lives there. For Wiesel the town is no longer another town, it is the face of that watch.

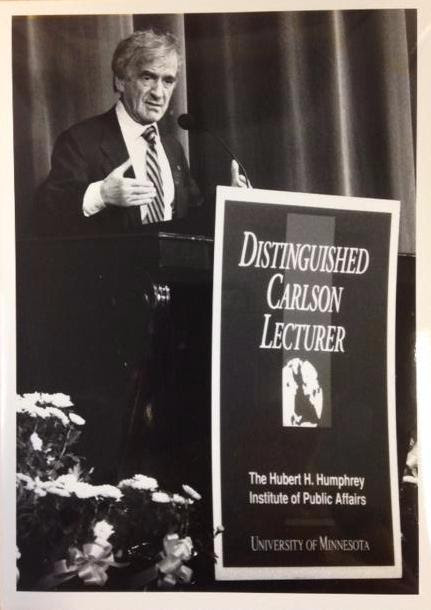

I was fortunate enough to meet Wiesel in November of 1998, when he gave a talk as part of the Carlson Lecture Series, co-sponsored by the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies at Northrop Auditorium. After the talk (which I remember very well), I was able to introduce myself. He was gracious and kind and listened intently as I spoke of “The Watch” with him. I remember him being surprised that I knew it; I cannot recall how long the conversation lasted, or anything more than the warmth of his smile and handshake, but he certainly made an impression on me. In 1999, I graduated with my Masters of Liberal Studies, specializing in Holocaust representation in the visual arts and have worked in the field in one capacity or another ever since.

I have been to Auschwitz and Birkenau more than once. For a week I walked back and forth under the infamous Arbeit macht freisign. I never was able to forget where I was, nor did it get easier to walk that path. In Birkenau I found myself looking at the ground, watching my feet tread the well-worn dirt paths. In a moment of heat and fatigue I sat upon the ruins of Canada, the sorting warehouse for the belongings brought by the transported. In a blur, I caught a glimmer of a shiny object by my right foot. Digging a bit, I uncovered a tiny pearl button. My mind raced, who did it belong too? Where did it come from? Why of all days, did it appear to me now? Trying to focus I could hear Wiesel’s voice reading the words of his story. Like him, I wanted to clean the button, keep it safe, bring it with me, give it life. In the end I put it back, I left it where it belonged. The dead needed to remain — it was up to me to remember, to educate.

Wiesel once said, “Man, as long as he lives, is immortal. One minute before his death he shall be immortal. But one minute later, God wins.” Certainly a true statement, and yet I believe we can safely argue that Wiesel in death will continue to live on through his words. I am not the first to be inspired by his writing nor will I be the last. Because of him the Holocaust will not be forgotten, and those of us he inspired will continue to bear witness, continue to stand up against injustice. Time nor death can ever take that from us.

Jodi Elowitz is an adjunct professor of the Humanities at Gateway Community College in Phoenix, Arizona, and former Program Coordinator for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Comments