Photo Of Ramadan Light On Top Of Table by Ahmed Aqtai is licensed under CC BY 2.0 in pexels.

In the United States, Islamophobia is at an all-time high. Muslim people have experienced increased discrimination including being singled out by airport security and other law enforcement individuals, being called offensive names, and experiencing physical threats of violence or attacks. Given that the Muslim population is continuing to grow, it is crucial to consider the experiences of Muslim people in the U.S. and the challenges they face.

Trends in Islamophobia

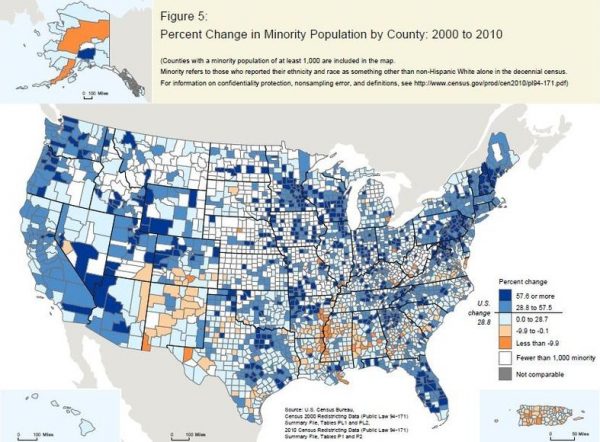

Muslim people do not make up a large population of the United States, comprising around 3 million people (or about 1.1% of the total US population) in 2017 and is projected to be 1.7% in 2030. And over the last decade, public perception of Muslim people has since trended towards unfavorable.

- Chris Bail. 2016. Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Joseph Gerteis and Nir Rotem. 2023. “Connecting the ‘Others’: White Anti-Semitic and Anti-Muslim Views in America.” The Sociological Quarterly 64(1): 144–64.

- Christine Ogan, Lars Willnat, Rosemary Pennington, and Manaf Bashir. 2014. “The Rise of Anti-Muslim Prejudice: Media and Islamophobia in Europe and the United States.” International Communication Gazette 76(1): 27–46.

The Impact of Media on Islamophobia

The media has played a critical role in shaping how the public perceives Muslim people in the U.S., including depicting discriminatory stereotypes of Muslim people as terrorists, violent, and backwards. For some, these representations have been used to justify violence and discrimination against Islamic people and institutions.

- Gabriel Ahmanideen and Derya Iner. 2024. “The Interaction between Online and Offline Islamophobia and Anti-Mosque Campaigns: The Literature Review with a Case Study from an Anti-Mosque Social Media Page.” Sociology Compass 18(1):e13160.

- David Altheide. 2017. Terrorism and the Politics of Fear. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Amir Saeed. 2007. “Media, Racism and Islamophobia: The Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Media.” Sociology Compass 1(2):443–62.

The Racialization of Muslim and Islamic Identity

The development of Islamophobia has been driven as well by the ways in which Muslim identity has become racialized in the U.S. and other parts of the world, an example of how “religion can be raced”. In particular, people “assign Muslim-ness” onto markers of Islam (such as wearing a hijab, having a beard, or wearing traditional clothing like a thobe or abaya) that are informed by cultural ideas and appearances. It is important to keep this racialization in mind when considering how Islamophobia manifests.

- Khaled A. Beydoun. 2019. American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Steve Garner and Saher Selod. 2015. “The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia.” Critical Sociology 41(1): 9–19.

- Joseph Gerteis, Douglas Hartmann, and Penny Edgell. 2020. “Racial, Religious, and Civic Dimensions of Anti-Muslim Sentiment in America.” Social Problems 67(4): 719–40.

- Saher Selod and David G. Embrick. 2013. “Racialization and Muslims: Situating the Muslim Experience in Race Scholarship.” Sociology Compass 7(8): 644–55.

Muslim is not a Monolith

It is important to resist the ”one-size-fits-all” stigmatized representations and stereotypes of an extremely diverse group of people. While public perceptions have conflated Arab and Middle Eastern identity solely with a singular Muslim category, Muslim people actually come from different ethnic groups that vary widely along beliefs, values, and more.

- Mehdi Bozorgmehr, Paul Ong, and Sarah Tosh. 2016. “Panethnicity Revisited: Contested Group Boundaries in the Post-9/11 Era.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39(5): 727–45.