As a student studying genocide and mass atrocity in the media, I often wonder whether we as consumers of the news can only take one atrocity at a time or if the media only thinks we can handle one at a time? Over the past year, I have watched as reporting on the atrocities in the Central Africa Republic, South Sudan and the campaign #BringBackOurGirls gain momentum only to lose it as quickly as it was gained.

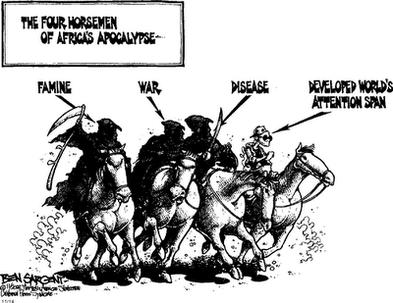

Now, almost all the news sources are focused on the Ebola outbreak in West Africa and it appears that the watchful eye of the media has moved away from the other hot spots. Apparently the news outlets have come to a consensus that we the audience have suffered from what Susan Moeller calls compassion fatigue and have moved from the black (famine) and red (war) horses of the apocalypse, in CAR and South Sudan, to the white horse (often referred to as infectious disease) of the apocalypse in West Africa. Compassion fatigue dictates that the news will only report on stories that resonate with an American audience and thus a focus on West Africa fits this understanding since two recent Ebola patients were American and that another patient who is British were airlifted to the UK for treatment. The shift to the white horse of the apocalypse has also seen the Democratic Republic of Congo make an appearance in the news this month and not for the on-going hostilities.

This new focus, however, should not be conflated necessarily as a concern for what the disease is doing to Liberian families and rural populations. This focus has been, almost singularly, how Ebola may affect the U.S. Thus Ebola is not seen as dangerous because of its brutal effects on Liberian, Guinean, and/or rural west African populations, it is dangerous because it may show up on these shores which is a trope that has been accurately critiqued as not only misinformed but as inherently racist as well. As someone that studies representation of atrocities in Africa in the media, this type of sensationalizing is one that is familiar. The creation of a sensational story sells newspapers and increases circulation numbers-only one horseman at a time. All four will cause too much panic and eventual disengagement.

As the academic year begins, this column will continue to highlight the flash-points across the continent. There will also be updates on the positive actions being taken in these dangerous areas, such as the continued peace efforts by several countries to end hostilities in South Sudan. It is my belief that this year will mostly be one of improvements more than it will be about renewed hostilities. However, two countries need to be on our radars this fall. The first country to keep an eye on is Nigeria as it prepares for elections in the spring and reports of soldiers blatantly refusing to obey orders to deploy against Boko Haram due to its being outmatched (in terms of weaponry) by the group. The other is Lesotho, which seems to either have barely missed a coup (at best) or (at worst) the coup plotters were testing the waters and may attempt another coup later.

Wahutu Siguru is the 2013 & Spring 2015 Badzin Fellow in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and PhD candidate in the Sociology department at the University of Minnesota. Siguru’s research interests are in the Sociology of Media, Genocide, Mass Violence and Atrocities (specifically on issues of representation of conflicts in Africa such as Darfur and Rwanda), Collective Memory, and perhaps somewhat tangentially Democracy and Development in Africa.

In June 2010, Daniel Schroeter, the Amos S. Deinard Memorial Chair in Jewish History at the University of Minnesota, and a member of the CHGS Faculty Advisory Board, co-taught a research workshop at the USHMM and began studying their voluminous collection of documents. He will be returning to Washington, DC, having been awarded the Ina Levine Invitational Scholar Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the USHMM for the 2014-2015 academic year.

In June 2010, Daniel Schroeter, the Amos S. Deinard Memorial Chair in Jewish History at the University of Minnesota, and a member of the CHGS Faculty Advisory Board, co-taught a research workshop at the USHMM and began studying their voluminous collection of documents. He will be returning to Washington, DC, having been awarded the Ina Levine Invitational Scholar Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the USHMM for the 2014-2015 academic year.

So how are these two events related? And why does it matter that we have only one definition of the Holocaust? We can debate whether the term “Holocaust” is the most fitting to describe the event, but there is no debate to what it signifies. Holocaust is the term that defines the destruction of the six million European Jews by the Nazi’s and their collaborators between 1933-1945.

So how are these two events related? And why does it matter that we have only one definition of the Holocaust? We can debate whether the term “Holocaust” is the most fitting to describe the event, but there is no debate to what it signifies. Holocaust is the term that defines the destruction of the six million European Jews by the Nazi’s and their collaborators between 1933-1945.

Margot De Wilde was born July 17, 1921, in Berlin, Germany. Margot lived in Holland at the time of the Nazi occupation in the late spring of 1940. Margot worked in the underground by delivering false passports and identification cards to Jews to aid them in leaving Holland. Margot and her husband were arrested when attempting to escape using these underground papers via train to Switzerland. Both were sent to Auschwitz where Margot’s husband later died.

Margot De Wilde was born July 17, 1921, in Berlin, Germany. Margot lived in Holland at the time of the Nazi occupation in the late spring of 1940. Margot worked in the underground by delivering false passports and identification cards to Jews to aid them in leaving Holland. Margot and her husband were arrested when attempting to escape using these underground papers via train to Switzerland. Both were sent to Auschwitz where Margot’s husband later died.