Wahutu Siguru sat down with Dr. Joachim Salvesberg from the University’s Sociology Department to discuss his new book, Representing Mass Violence: Conflicting Responses to Human Rights Violations in Darfur for the September edition of “Eye on Africa.”

Wahutu: What was the main motivation behind this current book, Representing Mass Violence: Conflicting Responses to Human Rights Violations in Darfur?

Prof. Savelsberg: You know that I have a longstanding interest in the way in which institutions of justice, and currently transitional justice, affect collective representations or collective memories of events, especially mass atrocities. And so, the motivation for this book on Darfur was to understand how interventions by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court (ICC) affect how global civil society thinks about such events, the way people imagine such events. And, part of the original design was to do a comparative study of eight countries. Even though the ICC is a global institution, the kinds of messages that it sends out, the kinds of representation of events that it offers are filtered by national institutions, they are reinforced by carrier groups in one country, but less so in another country. They find more receptive audiences in a country that has maybe dealt with mass atrocities in the past than in another country that hasn’t. So that was the main motivation, to understand how interventions, in this case by the UN Security Council and the ICC, affect the representation of Darfur in the public sphere. Initially I only thought of news media, that’s why we did a comparative analysis of newspapers in eight countries. And then, in the course of the research, I became aware that representations do not just differ by country but also by social fields. I was interested from the beginning in how human rights activists, and I selected Amnesty International as an example, talk about Darfur. How they reflect on the interventions by the ICC and the UN Security Council. But in my interviews I also ended up targeting a humanitarian aid NGO , for which I picked Doctors without Borders. I additionally interviewed diplomats from foreign ministries, or state departments if you want, and I saw that different fields talk in quite different terms about the violence in Darfur. Just as I was interested in the country-specific conditions that lead to a selective communication of ICC representations, so I became interested in the field-specific conditions that affect communication about Darfur.

Prof. Savelsberg: You know that I have a longstanding interest in the way in which institutions of justice, and currently transitional justice, affect collective representations or collective memories of events, especially mass atrocities. And so, the motivation for this book on Darfur was to understand how interventions by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court (ICC) affect how global civil society thinks about such events, the way people imagine such events. And, part of the original design was to do a comparative study of eight countries. Even though the ICC is a global institution, the kinds of messages that it sends out, the kinds of representation of events that it offers are filtered by national institutions, they are reinforced by carrier groups in one country, but less so in another country. They find more receptive audiences in a country that has maybe dealt with mass atrocities in the past than in another country that hasn’t. So that was the main motivation, to understand how interventions, in this case by the UN Security Council and the ICC, affect the representation of Darfur in the public sphere. Initially I only thought of news media, that’s why we did a comparative analysis of newspapers in eight countries. And then, in the course of the research, I became aware that representations do not just differ by country but also by social fields. I was interested from the beginning in how human rights activists, and I selected Amnesty International as an example, talk about Darfur. How they reflect on the interventions by the ICC and the UN Security Council. But in my interviews I also ended up targeting a humanitarian aid NGO , for which I picked Doctors without Borders. I additionally interviewed diplomats from foreign ministries, or state departments if you want, and I saw that different fields talk in quite different terms about the violence in Darfur. Just as I was interested in the country-specific conditions that lead to a selective communication of ICC representations, so I became interested in the field-specific conditions that affect communication about Darfur.

Wahutu: Previous work has not done this much data collection or analysis. From what you have said, the data collection and analysis seems like a really important part of how you wanted to do this project. Why was it important for you to do the interviews, to do the content analysis of news reports and travel to all of these countries?

Prof. Savelsberg: It was important for a number of reasons. The first reason is that we know that global institutions of justice like the ICC are extremely modern. Human history hasn’t really known them. We’ve known ad hoc courts in the twentieth century, but not a permanent international criminal court. We have very little systematic knowledge about the effects of these institutions. It would be desirable of course to measure the effect of ICC interventions on the future likelihood of genocide and crimes against humanity and war crimes. That would be a very tall order, and we will have to tackle this at some point. I wasn’t able to go that far, but one interim step is to think about how these interventions affect the way the world thinks about mass atrocities. It is not at all for granted that people in different countries take note of what is going on. Even if institutions like the ICC intervene, there is a long history of denial, of closing one’s eyes, especially if atrocities occur in a far-away place in the world. So it was very important to me to begin to systematically measure the effects of these sorts of interventions in a cautious way, by first looking at the impact they have on the degree to which and the way in which mass atrocities are represented and perceived.

Wahutu: What would you say was one of the most surprising findings that jumped out at you?

Prof. Savelsberg: There are a number of surprising findings. One of the things that really impressed me was when I conducted my interviews among diplomats who were interested in negotiating deals with the Sudanese government to establish peace; with humanitarian aid people who were interested in getting their aid on the ground and collaborating, say, with the Sudanese ministry of health; and with human rights activists. To see the seriousness with which all of these actors, many of whom impressed me deeply, pursued what they were doing. How at the same time their views of the violence differed depending on the role that especially the Sudanese state played in their respective fields. Diplomats need to negotiate with the Sudanese state, humanitarian aid workers need to collaborate with administrative units of the Sudanese state, and human rights activists don’t do that. But many of these people had been to Darfur, they had worked on the ground, they had also – the same is true for Africa correspondents – left the comfort of their homes in Philadelphia or Berlin or London only to spend years in rather tough settings, to witness situations that are not easy for people to bear. So many of these people impressed me profoundly. At the same time, I took note that each of them had a different view of the violence on the ground. So this is, if you want, a kind of sociology of knowledge exercise. You see how the world and events in the world take different shape, appear in a different light, when seen through different lenses, through different frames. So that’s one thing that surprised me and then there were many little observations pertaining to national particularities. For example we found in our media analysis that the term genocide was used relatively rarely in German news reports, which to me was counter intuitive, given Germany’s history of the Holocaust. But, in the interviews I conducted, I got a number of suggestions as to how to interpret such a finding. One Africa correspondent for a prominent German newspaper said that when he thought of genocide, he categorised the Holocaust under that label, and while knowing how horrific things were in Darfur, he had a hard time placing Darfur under the same category where in his mind the Holocaust was already placed. Or, the director of a major national Holocaust memorial institution in Germany said that the Americans could draw parallels between the Holocaust and Darfur – and this is a man who is a Rabbi and a son of an Auschwitz survivor – but as Germans, he said, we could not do that because as soon Germans drew a parallel between the Holocaust and events such as Darfur people would accuse them of trying to relativize what happened during the Holocaust. So there are cultural sensitivities in specific countries — and this is just one example from the German part of the study — that filter and generate caution towards the use of certain terms. Clearly Germany differs from the United States, for example, where the use of the term genocide and metaphorical bridging to the Holocaust was used very generously, and the explanation is relatively simple. It has to do with the strength of the Save Darfur movement in the US, and this strength had to do with the fact that there were a number of, in Weberian or Mannheimian terms, carrier groups that identified with the cause of Darfur. So there were African Americans who identified with the victims who were defined as ‘black Africans’. There were American Jews who, after the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington issued a genocide alert, identified with this cause, and there were evangelical Christians on the conservative side of the political spectrum who had done a lot of missionary work, not in Darfur but in South Sudan, but who therefore were quite sensitive to human rights violations in that country. So you have Germany and the United States as two examples where country specific sensitivities and carrier groups contribute to a different reception of the events in Darfur. At the same time both the United States and Germany were the two countries that stood out in terms of the intensity of reporting. German cultural sensitivities thus do not mean that German journalists didn’t take note, quite the opposite, despite their cautious use of the term genocide. The other noteworthy result is that indeed certain interventions by institutions like the ICC revived, every time they occurred, global interest in Darfur. The flattening of the pattern of attention that normally occurs soon after instances of mass violence was thus delayed by three or four years in the case of Darfur. The other noteworthy finding is that definitions by the criminal justice system are more strongly reflected in media reporting than the representation of events by diplomats or humanitarian aid organizations. Why this is the case is a separate question, and I have some ideas about this that I explore in the book. I have found similar patterns, by the way, on previous occasions like in my study on the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War.

Wahutu: What message do you hope a reader of your book gets from it when they read it?

Prof. Savelsberg: I think that the book would help people understand how mass violence that occurs in the global south, for example in Darfur, goes through a number of processes and filters before news about it reach us as member of civil society; understand the cultural and structural processes and the institutions that are embedded in different fields and that are associated with different countries; understand how that which happens on the ground, which almost none of us, very few people, will observe with our own eyes, reaches us as members of civil society, or maybe of global society; understand the process through which those events are filtered, or constructed if you want. So this helps us understand what it is that we learn about through public information about mass violence in the global south.

Wahutu: So what you are saying is that for a reader you hope that the message is that by the time they watch, read or hear about on going atrocities such as Darfur, they remember that it goes through several filtering processes to get to them. As such, is it then upon the reader to be a bit more active in seeking more information and seeking more diverse voices?

Prof. Savelsberg: Yes, I think the book provides us with the critical tools that we need in order to be mature consumers of these kinds of news. We read the news and, having read this book about Representing Mass Violence, we are in better position to understand what processes the events as they were written about and described have gone through before they reach us.

Wahutu: What are some of the challenges in writing such a book? You talk to professionals and practitioners form such diverse walks of life who, as much as they are dealing with getting the message out, have different constituencies. So what are some of the challenges in trying to navigate that terrain?

Prof. Savelsberg: Well, the main challenge was the huge effort at data collection. The media analysis had five research assistants who analysed more than 3000 news articles. To conduct the interview meant travelling to Berlin, Paris, London, Dublin, Zurich, Geneva, Vienna, Washington, New York, and so many other places. So it was a major effort just to collect the data. In the interview situations, it was important to capture the voices of these different actors that operate in distinct fields, not to impose of them my understanding of the situation, but to minimise the interviewer effect and to get their perception as clearly as possible. I think I succeeded in this, especially since people are so embedded in their fields; the way they see the world thus is so matter of course to them, and is reinforced by the institutions and educational process they have been exposed to.

Wahutu: So onto my last question. You book is available to download for free, what was the thinking behind that?

Prof. Savelsberg: For the publisher, the University of California Press, the thinking behind this was that books used to sell many copies to university libraries, which brought in their expenses, on the average anyway, so they didn’t run a deficit. University libraries have change their purchasing practices. They have smaller budgets now, they can’t buy as many books, and they buy more electronic sources than paper products. So the presses are really under pressure to come up with new models of funding publications. In my case they offered me either to go the traditional way or to use this innovative model, and I chose the innovative way for a number of reasons. An important reason is that I think this mechanism will allow for a better distribution of the book, and especially a book dealing with mass violence in the global south, in which many people who’d be interested in the subject don’t have an easy time to just write somewhere and order a paper copy and pay for it. So this model will increase availability particularly in those parts of the world that I would like to reach with my book but that may not as easily get a hold of the paper copy. Do I pay a price for it? Yes I had to waive any royalties, but that was easy for me to do.

Wahutu: Thank you so much for agreeing to do this.

Prof. Savelsberg: You are welcome, Wahutu.

Wahutu Siguru is Badzin Fellow in Holocaust and Genocide Studies and PhD candidate in the Sociology department at the University of Minnesota. Siguru’s research interests are in the Sociology of Media, Genocide, Mass Violence and Atrocities (specifically on issues of representation of conflicts in Africa such as Darfur and Rwanda), Collective Memory, and perhaps somewhat tangentially Democracy and Development in Africa.

The Twitter account

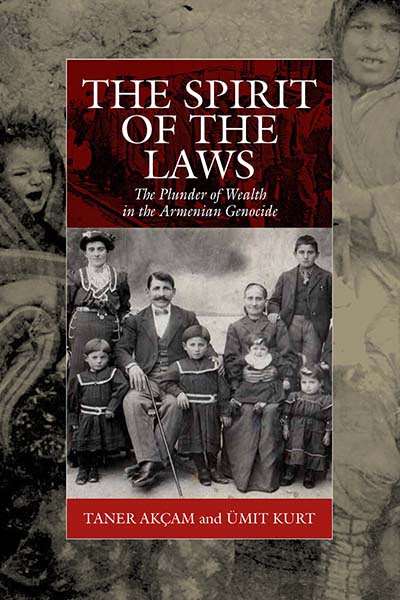

The Twitter account  Pertinent to contemporary demands for reparations from Turkey is the relationship between law and property in connection with the Armenian Genocide. This book examines the confiscation of Armenian properties during the genocide and subsequent attempts to retain seized Armenian wealth. Through the close analysis of laws and treaties, it reveals that decrees issued during the genocide constitute central pillars of the Turkish system of property rights, retaining their legal validity, and although Turkey has acceded through international agreements to return Armenian properties, it continues to refuse to do so. The book demonstrates that genocides do not depend on the abolition of the legal system and elimination of rights, but that, on the contrary, the perpetrators of genocide manipulate the legal system to facilitate their plans.

Pertinent to contemporary demands for reparations from Turkey is the relationship between law and property in connection with the Armenian Genocide. This book examines the confiscation of Armenian properties during the genocide and subsequent attempts to retain seized Armenian wealth. Through the close analysis of laws and treaties, it reveals that decrees issued during the genocide constitute central pillars of the Turkish system of property rights, retaining their legal validity, and although Turkey has acceded through international agreements to return Armenian properties, it continues to refuse to do so. The book demonstrates that genocides do not depend on the abolition of the legal system and elimination of rights, but that, on the contrary, the perpetrators of genocide manipulate the legal system to facilitate their plans.

Coincidentally, this random interaction occurred only two days after the 20th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, which took place on July 11, 1995. It made me ponder the use of the word ‘our’ in this brief conversation. We all clearly still have a lot in common: the primary, and perhaps strongest, connection being the language. ‘Our’ language, as the security agent used it, refers to Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian. However, in ‘our’ language, there is still a contention over what happened in Srebrenica. Recently, Russia, Serbia’s ally, had vetoed the UN Security Council measure that labeled Srebrenica a genocide. Killing people based on their identity is a very basic definition of genocide, and denying that is to politicize it once again, and take away from the core of what this event should represent 20 years later, which is healing and hope for the future.

Coincidentally, this random interaction occurred only two days after the 20th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, which took place on July 11, 1995. It made me ponder the use of the word ‘our’ in this brief conversation. We all clearly still have a lot in common: the primary, and perhaps strongest, connection being the language. ‘Our’ language, as the security agent used it, refers to Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian. However, in ‘our’ language, there is still a contention over what happened in Srebrenica. Recently, Russia, Serbia’s ally, had vetoed the UN Security Council measure that labeled Srebrenica a genocide. Killing people based on their identity is a very basic definition of genocide, and denying that is to politicize it once again, and take away from the core of what this event should represent 20 years later, which is healing and hope for the future. How do interventions by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court influence representations of mass violence? What images arise instead from the humanitarianism and diplomacy fields? How are these competing perspectives communicated to the public via mass media? Zooming in on the case of Darfur, Joachim J. Savelsberg analyzes more than three thousand news reports and opinion pieces and interviews leading newspaper correspondents, NGO experts, and foreign ministry officials from eight countries to show the dramatic differences in the framing of mass violence around the world and across social fields.

How do interventions by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court influence representations of mass violence? What images arise instead from the humanitarianism and diplomacy fields? How are these competing perspectives communicated to the public via mass media? Zooming in on the case of Darfur, Joachim J. Savelsberg analyzes more than three thousand news reports and opinion pieces and interviews leading newspaper correspondents, NGO experts, and foreign ministry officials from eight countries to show the dramatic differences in the framing of mass violence around the world and across social fields. Prof. Savelsberg: You know that I have a longstanding interest in the way in which institutions of justice, and currently transitional justice, affect collective representations or collective memories of events, especially mass atrocities. And so, the motivation for this book on Darfur was to understand how interventions by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court (ICC) affect how global civil society thinks about such events, the way people imagine such events. And, part of the original design was to do a comparative study of eight countries. Even though the ICC is a global institution, the kinds of messages that it sends out, the kinds of representation of events that it offers are filtered by national institutions, they are reinforced by carrier groups in one country, but less so in another country. They find more receptive audiences in a country that has maybe dealt with mass atrocities in the past than in another country that hasn’t. So that was the main motivation, to understand how interventions, in this case by the UN Security Council and the ICC, affect the representation of Darfur in the public sphere. Initially I only thought of news media, that’s why we did a comparative analysis of newspapers in eight countries. And then, in the course of the research, I became aware that representations do not just differ by country but also by social fields. I was interested from the beginning in how human rights activists, and I selected Amnesty International as an example, talk about Darfur. How they reflect on the interventions by the ICC and the UN Security Council. But in my interviews I also ended up targeting a humanitarian aid NGO , for which I picked Doctors without Borders. I additionally interviewed diplomats from foreign ministries, or state departments if you want, and I saw that different fields talk in quite different terms about the violence in Darfur. Just as I was interested in the country-specific conditions that lead to a selective communication of ICC representations, so I became interested in the field-specific conditions that affect communication about Darfur.

Prof. Savelsberg: You know that I have a longstanding interest in the way in which institutions of justice, and currently transitional justice, affect collective representations or collective memories of events, especially mass atrocities. And so, the motivation for this book on Darfur was to understand how interventions by the UN Security Council and the International Criminal Court (ICC) affect how global civil society thinks about such events, the way people imagine such events. And, part of the original design was to do a comparative study of eight countries. Even though the ICC is a global institution, the kinds of messages that it sends out, the kinds of representation of events that it offers are filtered by national institutions, they are reinforced by carrier groups in one country, but less so in another country. They find more receptive audiences in a country that has maybe dealt with mass atrocities in the past than in another country that hasn’t. So that was the main motivation, to understand how interventions, in this case by the UN Security Council and the ICC, affect the representation of Darfur in the public sphere. Initially I only thought of news media, that’s why we did a comparative analysis of newspapers in eight countries. And then, in the course of the research, I became aware that representations do not just differ by country but also by social fields. I was interested from the beginning in how human rights activists, and I selected Amnesty International as an example, talk about Darfur. How they reflect on the interventions by the ICC and the UN Security Council. But in my interviews I also ended up targeting a humanitarian aid NGO , for which I picked Doctors without Borders. I additionally interviewed diplomats from foreign ministries, or state departments if you want, and I saw that different fields talk in quite different terms about the violence in Darfur. Just as I was interested in the country-specific conditions that lead to a selective communication of ICC representations, so I became interested in the field-specific conditions that affect communication about Darfur.

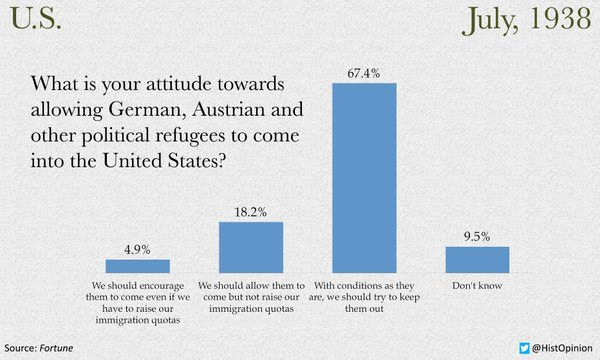

And it was not just Irene’s talk that provided a face to those that were lost. Adam also did a great job in offering a human element to the story. He was helped in part by his refusal to create black-and-white narrative. Indeed, saying, “all Germans were Nazis” and that “all Jews helpless sheep” does a tremendous disservice to the complexity and tragedy of the events that comprise the Holocaust. Nothing was inevitable. Conscious actors made decisions to participate. “How” and “why” are more difficult questions to answer, and as such were the central focus of Adam’s course.

And it was not just Irene’s talk that provided a face to those that were lost. Adam also did a great job in offering a human element to the story. He was helped in part by his refusal to create black-and-white narrative. Indeed, saying, “all Germans were Nazis” and that “all Jews helpless sheep” does a tremendous disservice to the complexity and tragedy of the events that comprise the Holocaust. Nothing was inevitable. Conscious actors made decisions to participate. “How” and “why” are more difficult questions to answer, and as such were the central focus of Adam’s course.