Who was Benjamin Murmelstein? Why would Claude Lanzmann dedicate over 3 hours to him in his latest film The Last of the Unjust? Murmelstein was a rabbi and teacher from Vienna, third Jewish elder of the Thereseinstadt ghetto, and the only surviving Jewish elder of any of the Jewish Councils set up by the Nazis. Condemned by many in the Jewish Community as a traitor and a Nazi collaborator he was tried and acquitted by the Czech authorities after the war settling in exile in Rome where he lived until his death in 1989.

He testified at the trial of Thereseinstadt Commandant Karl Rahm and wrote and published a book of his experiences in Terezin: Il ghetto-modello di Eichmann (Theresienstadt: Eichmann’s Model Ghetto), in 1961. He submitted the book to Israeli prosecutors to use at the Eichmann trial (Adolf Eichmann, SS officer in charge of the deportation of the Jews of Europe) a submission that went unused.

He testified at the trial of Thereseinstadt Commandant Karl Rahm and wrote and published a book of his experiences in Terezin: Il ghetto-modello di Eichmann (Theresienstadt: Eichmann’s Model Ghetto), in 1961. He submitted the book to Israeli prosecutors to use at the Eichmann trial (Adolf Eichmann, SS officer in charge of the deportation of the Jews of Europe) a submission that went unused.

Murmelstein had much valuable information to offer, especially on Eichmann So much so that if Murmelstein’s testimony had been used it would have dispelled any notion of the dispassionate Nazi bureaucrat who only followed orders as defined by Hannah Arendt’s term the “banality of evil.” Instead we would have seen Eichmann as a man who loved his job and pursued it with zeal and passion above and beyond what was required by his superiors. We would also have seen a corrupt man who lined his own pockets with Jewish funds for both personal and professional gain, as the extra money afforded him the financial independence to run his department apart of the bureaucratic machine and away from the eyes of his superiors.

So why is Murmelstein’s story coming to light now and why did Lanzmann wait nearly 40 years to make this film? Possibly the world was not ready for such a controversial and ambivalent figure. In 1975 Lanzmann interviewed Murmelstein for a project he was working on which later became the critically acclaimed 9-hour documentary Shoah. The interviews show that Murmelstein lived in the center of what Primo Levi referred to as the “grey zone” in his book The Drowned and the Saved. Levi’s theory is that those of us who did not experience the lager (camps) and ghettos cannot place ourselves in a position to judge those that were there, nor can we view the Holocaust as something that is black or white, good or evil. We simply cannot know what we would do to survive under the circumstances.

Murmelstein is clear that he was no saint and that he loved power, danger and adventure that went with the job of being a Jewish community leader and later elder. But he also speaks in terms of the expectations that others had in times that were not ordinary. Murmelstein towards the end of the film tells Lanzmann that in Thereisenstadt there were no saints. “There were martyrs, but martyrs are not necessarily saints.”

Murmelstein points out that many people tried to conduct life as they had under normal circumstances but there was nothing normal about Thereseinstadt, the model ghetto the Nazis had created to fool the world and the Jews imprisoned there about the “Final Solution.” While Murmelstein claims his intentions were to save as many Jews as he could, others viewed him as a tyrant, a collaborator, and a man who only cared about himself. Yet many times in the interviews Murmelstein speaks of the opportunities he had to escape with his family to England and to Palestine, but he remained feeling it was his responsibility.

As the film begins we watch the now 87-year-old Lanzmann read from Murmelstein’s book in Prague, Nisko, and Theresienstadt. One might wonder if this is an egotistical ploy by Lanzmann, but as the Murmelstein interviews unfold and the 3 1/2 hours go by we realize that Lanzmann has a real affection for Murmelstein, so much so he has become a surrogate witness. Lanzmann has become Murmelstein’s voice, reading passages of his beautifully worded testimony in the places that Murmesltein describes, thus collapsing time, bringing past and present together in the same space, much as he did in Shoah.

Here amidst the past and present we hear Murmelstein in his own words, we are drawn to Murmelstein much like Lanzmann is by his bold storytelling, his intelligence, knowledge of mythology, literature and history. He seems to be telling the truth about his experiences, admitting to his flaws and the perceptions of his decisions.

The Last of the Unjust will not be remembered as a landmark documentary about the Holocaust like Shoah. Still, it is an important work that represents a different approach to Holocaust documentary. Lanzmann acts as a surrogate witness, in this case representing an extraordinary and at the same time flawed character steeped in moral ambivalence. Lanzmann offers the viewer a much more complex and deeper understanding of humanity during the Shoah by giving a voice to a survivor whose testimony was silenced by those who were not yet ready to hear what he had to say.

Jodi Elowitz is the Outreach Coordinator for CHGS and the Program Coordinator for the European Studies Consortium. Elowitz is currently working on Holocaust memory in Poland and artistic representation of the Holocaust in animated short films.

Commemorating the Holocaust: The Dilemmas of Remembrance in France and Italy reveals how and why the Holocaust came to play a prominent role in French and Italian political culture in the period after the end of the Cold War. By charting the development of official, national Holocaust commemorations in France and Italy, Rebecca Clifford explains why the wartime persecution of Jews, a topic ignored or marginalized in political discourse through much of the Cold War period, came to be a subject of intense and often controversial debate in the 1990s and 2000s.

Commemorating the Holocaust: The Dilemmas of Remembrance in France and Italy reveals how and why the Holocaust came to play a prominent role in French and Italian political culture in the period after the end of the Cold War. By charting the development of official, national Holocaust commemorations in France and Italy, Rebecca Clifford explains why the wartime persecution of Jews, a topic ignored or marginalized in political discourse through much of the Cold War period, came to be a subject of intense and often controversial debate in the 1990s and 2000s.

Noemi Schory, a documentary film director and producer, was the Schusterman Visiting Artist in Residence at the Center for Jewish Studies 2013 Fall Semester. Schory taught The Holocaust in Film: Recent Israeli and German Documentaries Compared and spoke at various film screenings and events on campus and in the community. Schory produced the award-winning documentary film “

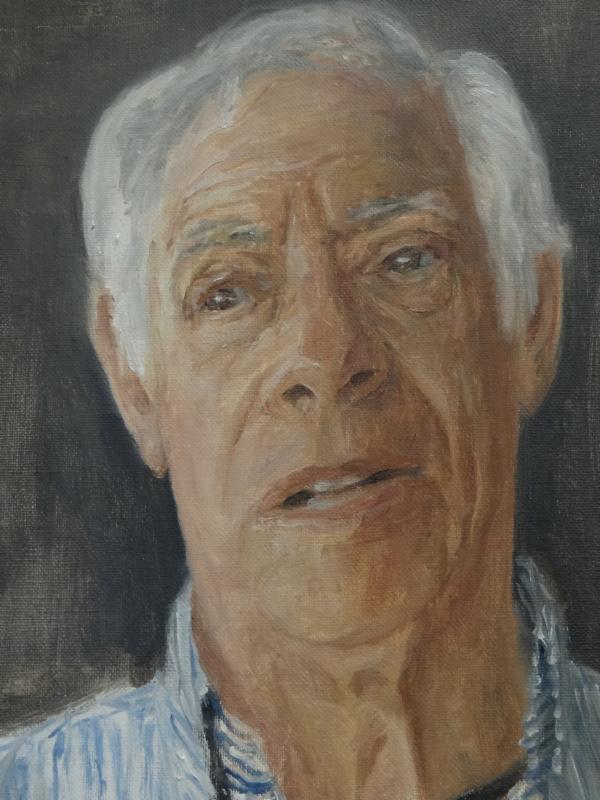

Noemi Schory, a documentary film director and producer, was the Schusterman Visiting Artist in Residence at the Center for Jewish Studies 2013 Fall Semester. Schory taught The Holocaust in Film: Recent Israeli and German Documentaries Compared and spoke at various film screenings and events on campus and in the community. Schory produced the award-winning documentary film “ Although Gus was a child during the Holocaust, he spoke often about remembering the events of Kristallnacht (the Nazi pogrom) that took place throughout Germany and Austria on November 9,10, 1938. “I was just a small child in Hildesheim when my father held me up to see the smoke coming from our beloved synagogue. The experience was so embedded in my memory I even wrote a play, “Guests of the City,” about my return to Germany with flashbacks to that time which was produced and performed in my home town Hildesheim in 2005 (I played my father).”

Although Gus was a child during the Holocaust, he spoke often about remembering the events of Kristallnacht (the Nazi pogrom) that took place throughout Germany and Austria on November 9,10, 1938. “I was just a small child in Hildesheim when my father held me up to see the smoke coming from our beloved synagogue. The experience was so embedded in my memory I even wrote a play, “Guests of the City,” about my return to Germany with flashbacks to that time which was produced and performed in my home town Hildesheim in 2005 (I played my father).” Since the end of Communism, Jews from around the world have visited Poland to tour Holocaust-related sites. A few venture further, seeking to learn about their own Polish roots and connect with contemporary Poles. For their part, a growing number of Poles are fascinated by all things Jewish. Erica T. Lehrer explores the intersection of Polish and Jewish memory projects in the historically Jewish neighborhood of Kazimierz in Krakow. Her own journey becomes part of the story as she demonstrates that Jews and Poles use spaces, institutions, interpersonal exchanges, and cultural representations to make sense of their historical inheritances.

Since the end of Communism, Jews from around the world have visited Poland to tour Holocaust-related sites. A few venture further, seeking to learn about their own Polish roots and connect with contemporary Poles. For their part, a growing number of Poles are fascinated by all things Jewish. Erica T. Lehrer explores the intersection of Polish and Jewish memory projects in the historically Jewish neighborhood of Kazimierz in Krakow. Her own journey becomes part of the story as she demonstrates that Jews and Poles use spaces, institutions, interpersonal exchanges, and cultural representations to make sense of their historical inheritances. On the 5th of December, the UN voted to allow the French to send 400 troops into the CAR who would augment the already present AU battalion of 3600. The French intend on increasing this number to 1200 troops in the coming days following a sudden outbreak of killings within the last fortnight of women and children by Séléka forces (meaning ‘union’ in the Sangolanguage) that has resulted in 500 deaths and 189,000 fleeing their homes in Bangui. Fears of retaliatory attacks have become more pronounced leading both Burundi and Rwandato pledge to send troops to the country. While the number of deaths might seem deceptively low for a nation of about 4.6 million, it only accounts for Bangui since correspondents have not been able to venture outside that area.

On the 5th of December, the UN voted to allow the French to send 400 troops into the CAR who would augment the already present AU battalion of 3600. The French intend on increasing this number to 1200 troops in the coming days following a sudden outbreak of killings within the last fortnight of women and children by Séléka forces (meaning ‘union’ in the Sangolanguage) that has resulted in 500 deaths and 189,000 fleeing their homes in Bangui. Fears of retaliatory attacks have become more pronounced leading both Burundi and Rwandato pledge to send troops to the country. While the number of deaths might seem deceptively low for a nation of about 4.6 million, it only accounts for Bangui since correspondents have not been able to venture outside that area. He testified at the trial of

He testified at the trial of  What did people hear about Kristallnacht outside of Germany in 1938 from governments and media sources? How did governments and ordinary people respond to the plight of the Jewish community there? How have lives been affected by Kristallnacht in the seventy years since its occurrence? This interdisciplinary study of erasure and enshrinement seeks to answer these questions, exploring issues of memory and forgetting (in both the material and symbolic sense), and how the meaning of Kristallnacht has been altered by various actors since 1938.

What did people hear about Kristallnacht outside of Germany in 1938 from governments and media sources? How did governments and ordinary people respond to the plight of the Jewish community there? How have lives been affected by Kristallnacht in the seventy years since its occurrence? This interdisciplinary study of erasure and enshrinement seeks to answer these questions, exploring issues of memory and forgetting (in both the material and symbolic sense), and how the meaning of Kristallnacht has been altered by various actors since 1938.